![]()

![]() Thanks for voting for Anne in the Three Quarks Daily contest. She’s been voted into the semi-finals round, and now it is up to the editors of 3QD and the judges. Do check out the list of other semi-finalists; they are all excellent reads and the geo- and enviro-sciences are well-represented.

Thanks for voting for Anne in the Three Quarks Daily contest. She’s been voted into the semi-finals round, and now it is up to the editors of 3QD and the judges. Do check out the list of other semi-finalists; they are all excellent reads and the geo- and enviro-sciences are well-represented.

Earthquakes and Tsunami

- Excellent article on tsunami disaster response modeling for Cannon Beach, Oregon:

http://www.kgw.com/news/local/OR-computer-simulation-guides-tsunami-planning-123479259.html

(via @lockwooddewitt)

Volcanoes

- Gorgeous wind shift in the plume: incredible image of Puyehue ash blown into Argentina

http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/NaturalHazards/view.php?id=50858

(via @ugrandite, @clasticdetritus, @NASA_EO)

Landslides

- Slow-Motion Landslide Threatens Homes In New York, as covered on @nprnews and Geology in Motion;

http://www.npr.org/2011/06/06/136935162/slow-motion-landslide-threatens-homes-in-new-york

http://www.geologyinmotion.com/2011/06/largest-landslide-in-new-york-state-82.html

Fossils

- What did plesiosaurs do with their long necks? @Laelaps looks at the clues:

http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2011/06/plesiosaurs-the-beautiful-bottom-feeders/ - Traces of early, pre-snowball earth biomineralisers found Yukon, Canada

http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2011/ancient-armor-microfossils-0607.html

(via @highlyanne)

(Paleo)climate

- OK, this is pretty scary: the release of carbon into the atmosphere today is nearly 10 times as fast as during Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum.

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/06/110605132433.htm - Fascinating: how warm water leaking into Atlantic from Indian Ocean strongly affects climate of S America & Europe

http://deepseanews.com/2011/06/the-indian-oceans-cup-runeth-over/ - “The public thinks scientists are divided on global warming, when it just ain’t true.” Good post summarizing the disconnect between public perception and scientific consensus, by Wild Weather Dan.

http://blogs.agu.org/wildwildscience/2011/06/08/the-great-american-disconnect/

(via @para_sight) - Bill McKibben wrote an op-ed in the Washington Post a few weeks ago about seeing a pattern in individual events. While we don’t understand tornadoes and their historical record well enough to say whether their frequency or intensity is being affected by climate change, this dramatization of McKibben’s editorial makes a very powerful point:

- Elizabeth Kolbert echoes a similar refrain in The @NewYorker on climate change, extreme weather, and politics.

http://www.newyorker.com/talk/comment/2011/06/13/110613taco_talk_kolbert

(via @YaleE360, ) - Recent snowpack declines in the Rocky Mountains are out of the ordinary, compared to a long tree-ring record [I need to read the paper]

http://www.doi.gov/news/pressreleases/USGS-Study-Finds-Recent-Snowpack-Declines-in-the-Rocky-Mountains-Unusual-Compared-to-Past-Few-Centuries.cfm#

(via @WaterWired)Water

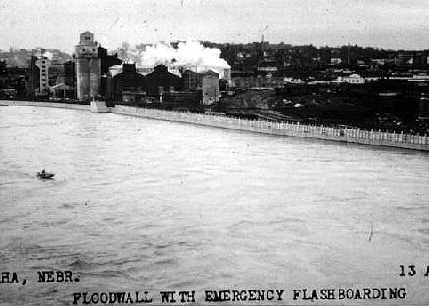

- For more flood links, check out Anne’s mid-week post on the Mississippi, Missouri, and Chinese floods:

https://all-geo.org/highlyallochthonous/2011/06/flooding-around-the-world-2/ - Worth a watch. Reeks with hubris but a good overview of this year’s Mississippi flood: USACE video

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SiPqy76vPtM&feature=player_profilepage

(via @WaterWired) - Lots of aerial photos of Missouri River Flooding near Pierre, SD

http://www.nylen.com/flood/20110610/

http://www.disasterrecovery.sd.gov/photogal/Pierre/gallery_Jun6.aspx(Check out the whirlpool!)

(via @TheGeoEngineer) - In Historic Flooding On Mississippi River, A Missed Opportunity To Rebuild Louisiana:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/06/09/in-historic-flooding-on-m_n_873623.html - China is threatening Egypt’s claims to the Nile water, by buying land upstream

http://www.csmonitor.com/Business/Green-Economics/2011/0604/For-Egypt-China-is-threatening-the-Nile

(via @WanderingGaia) - Two Elwha River (WA) dams unplugged last week, in prep for removal this fall, restoring salmon runs.

http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/localnews/2015202387_elwha02m.html

(via @WaterWired) - Fun video of geese surfing a wave on the Colorado River at a 27-year high flow!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xQfSx6zEey0&feature=share - NGWA Conference: Groundwater: Cities,Suburbs & Growth Areas \u2014 Remedying the Past/Managing for Future [Wish I’d known about this one earlier.]

http://www.ngwa.org/DEVELOPMENT/conferences/details/5026/index.aspx?CFID=733719&CFTOKEN=60984258

(via @WaterWired) - Philadelphia gets approval for its green water infrastructure, principally better storm water management

http://www.americanrivers.org/newsroom/blog/lgarland-20110608-pennsylvania-supports.html

(via @cynthiabarnett) - Can California further reduce urban water use? By following Australia’s example it can

http://wp.me/p17k4l-7Y

(via @chanceofraincom)

Environmental

- Knock-on effect of Mississipi flooding: displaced fertiliser may lead to largest-ever dead zone in Gulf of Mexico.

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/03/science/earth/03runoff.html - Five Years On, Java Still Grapples with Mud Volcano

http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2076148,00.html

Planets

- Voyager probes flying through turbulent magnetic ‘bubbles’ 10s of millions of km across at edge of the solar system

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-13715764 - A lovely overview of the Voyager missions. Looks like the original chief scientist, who is now in his 70s, still runs the show…

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-13704153

General Geology

- Remember the rediscovery of the Pink Terraces beneath Lake Rotomahana in New Zealand? Now they’ve found the White Terraces too.

http://juliansrockandiceblog.blogspot.com/2011/06/white-terraces-reappear-after-125-years.html - Accretionary Wedge #34 encore at @Dhunterauthor’s includes some more great posts.

http://entequilaesverdad.blogspot.com/2011/06/accretionary-wedge-34-encore.html - Meanwhile, in preparation for her hosting of the next Accretionary Wedge, Evelyn writes about…Accretionary Wedges.

http://georneys.blogspot.com/2011/06/geology-word-of-week-is-for.html - A taste of nostalgia for Chris in Brian Romans’ Friday Field Photo: cross-bedded quartzites from Table Mountain in Cape Town.

http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2011/06/friday-field-photo-147-cape-town-cross-bedding/ - I hope the buyers of these dinosaurs, meteorites, minerals, and a giant ground sloth up for auction put them on display so that people can see them.

http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2011/06/dinosaur-auction-gallery/

(via @wiredscience) - This year’s annual Geological Society of America meeting in Minneapolis is 9-12 Oct. Registration begins today at

http://www.geosociety.org/meetings/2011/reg.h

(via @geosociety) - Cool photo: Seafloor Sunday no. 87 – Debris left by icebergs plowing into the seabed in Antarctica

http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2011/06/seafloor-sunday-87-icebergs-plowing-into-the-seabed/

(via @clasticdetritus)

Interesting Miscellaney

- Thinking about an academic career? Be sure to check out SERC’s June 2011 workshop:

http://serc.carleton.edu/NAGTWorkshops/careerdev/AcademicCareer2011/june_2011.html

(via @ugrandite) - Using group dynamics to prevent tragedy of the commons: ‘complex network of small groups’ better than one big one?

http://arstechnica.com/science/news/2011/06/group-dynamics-key-to-avoiding-tragedy-of-the-commons.ars - Not only do people have bad instincts when it comes to probability and statistics, but its easy to exploit them.

http://arstechnica.com/science/news/2011/06/risk-probability-and-how-our-brains-are-easily-misled.ars - There Is No Such Thing as a Free Market [we only see the restrictions/regulations we don’t like]

http://www.truthout.org/there-no-such-thing-free-market/1307462405

(via @TheBrowser) - Another reason to lust for an i-Pad: NSF Science360

hhttp://itunes.apple.com/us/app/science360-for-ipad/id439928181?mt=8

(via @BoraZ) - "You can see that things gradually become more terrifying…" The alkali metals in water, via

http://blogs.scienceforums.net/swansont/archives/8868

(via @drskyskull, @swansontea)

- For more flood links, check out Anne’s mid-week post on the Mississippi, Missouri, and Chinese floods:

Nice plan for content warnings on Mastodon and the Fediverse. Now you need a Mastodon/Fediverse button on this blog.