It’s now been almost a year since NASA’s InSight lander – home of the first seismograph ever deployed on Mars – was declared dead. But the picture of the Red Planet’s interior being deduced from the four years of seismic data it collected continues to evolve.

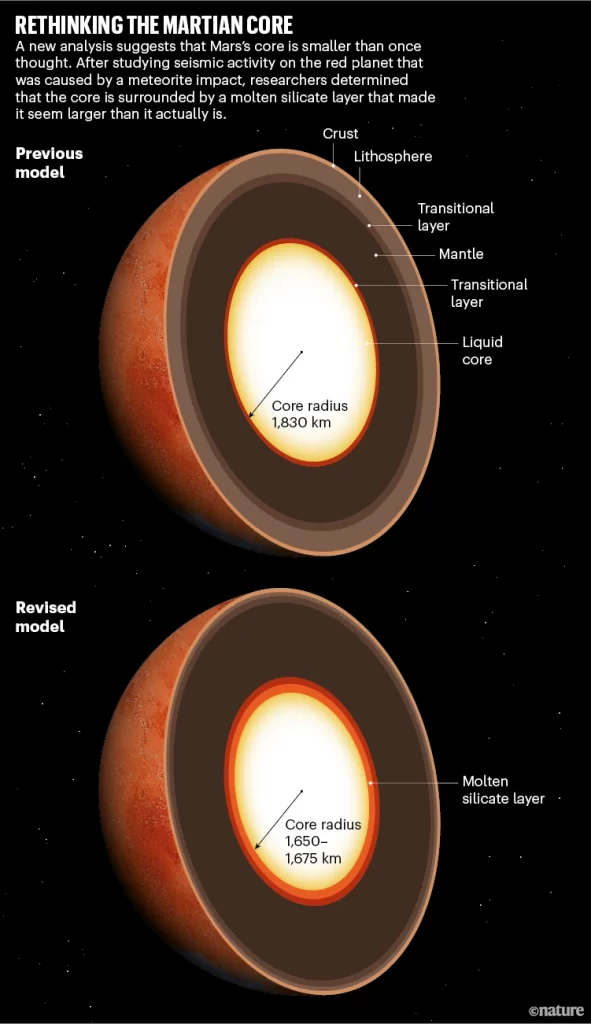

A previous study identified seismic waves bouncing off a transition between solid and liquid, assumed to be the core-mantle boundary, around 1500 km down, giving the core a radius of around 1800 km out of a total planetary radius of 3390 km. This implied that in addition to dense, molten iron and nickel, there were also a lot of lighter elements like sulphur, carbon and oxygen hanging around in the Martian core – otherwise Mars’s gravity would be significantly higher than it is.

Between then and the end of InSight’s life, a marsquake on the far side of the planet from the lander produced waves that diffracted around the core mantle boundary. The travel time of these waves compared to ones that only travelled through the upper mantle did not fit the old model. To explain the new data, it is now proposed that the previously detected boundary between solid and liquid is in the lower mantle, and that the (also liquid) core is enclosed by a layer of molten silicates around 150 km thick. This reduces the core radius to about 1,650 km, which might not seem much, but reduces the volume of the core by about a quarter, allowing it to be significantly denser and have a more realistic composition.

This isn’t actually the first body in the solar system inferred to have a structure like this: the moon is also thought to have a molten mantle boundary layer of very similar dimensions above its core. In both cases, it impedes heat transfer out of the core, allowing it to stay hot (and molten) and also inhibiting magnetic field generation. Which explains why both the Moon and Mars – small worlds whose interiors should cool down pretty quickly – still have at least partially liquid cores.

The origins of the molten boundary layer itself are a little mysterious to me, so I’m not clear on why the Earth does not have such a layer. Is it a size thing, or a ‘our planet is weird’ thing? And here’s a speculative thought: we still don’t know why Venus doesn’t have a magnetic field. What if it’s because it also has a molten mantle boundary layer?

Nice plan for content warnings on Mastodon and the Fediverse. Now you need a Mastodon/Fediverse button on this blog.