![]() When Hurricane Isaac passed over New Orleans as a Category 1 storm on the seventh anniversary of the disastrous Hurricane Katrina, everyone in the US let out a big sigh of relief. A category 1 storm, the lowest level of hurricane intensity on the Saffir-Simpson scale, meant sustained winds in the 74-95 mile per hour (119-153 km/hr) range, which are described as “very dangerous winds [that] will produce some damage.” There were few, if any, mandatory evacuation orders in Louisiana, and the media interviewed people saying that they heard Isaac would be a Category 1 storm so they “didn’t think it would be that bad.” Those people opted to stay in their homes Louisiana’s Plaquemines Parish, along the Mississippi River near New Orleans. Indeed, as the early reports from Louisiana came out, it sounded as if the storm had been relatively low in drama.

When Hurricane Isaac passed over New Orleans as a Category 1 storm on the seventh anniversary of the disastrous Hurricane Katrina, everyone in the US let out a big sigh of relief. A category 1 storm, the lowest level of hurricane intensity on the Saffir-Simpson scale, meant sustained winds in the 74-95 mile per hour (119-153 km/hr) range, which are described as “very dangerous winds [that] will produce some damage.” There were few, if any, mandatory evacuation orders in Louisiana, and the media interviewed people saying that they heard Isaac would be a Category 1 storm so they “didn’t think it would be that bad.” Those people opted to stay in their homes Louisiana’s Plaquemines Parish, along the Mississippi River near New Orleans. Indeed, as the early reports from Louisiana came out, it sounded as if the storm had been relatively low in drama.

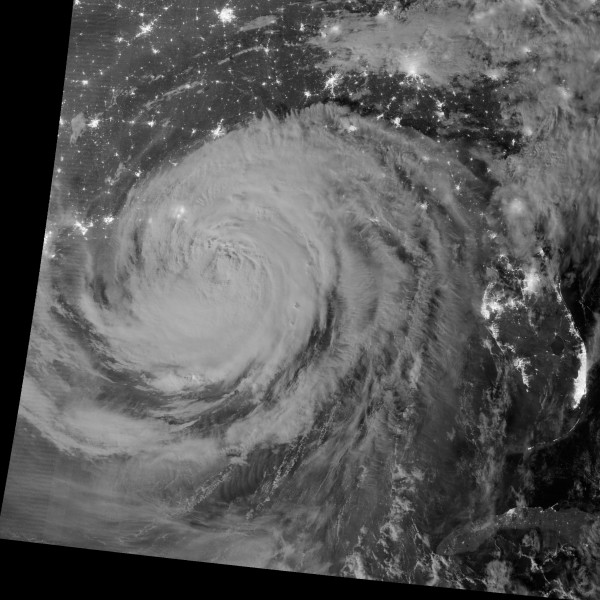

This will be the iconic image of Hurricane Isaac. NASA/NOAA/DoD VIIRS image of the hurricanes clouds superimposed on the city lights on the southeastern US. All those clouds are full of water. Image source: http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/NaturalHazards/view.php?id=79023

Only later did reports start to trickle out of levees overtopped, and people stranded on rooftops and in attics, being rescued by neighbors with boats. The flooding this time wasn’t in New Orleans itself, but in nearby Plaquemines Parish, where levee upgrades weren’t scheduled to be completed for a few more years. At least one levee overtopped, flooding the town of Braithwaite and surrounding areas where about 1700 people live, with up to 4.3 m (14 ft) of water. That water ended up trapped between the federal, main Mississippi River levee and more locally managed back levees. State officials have now breached those back levees to more quickly drain the water out of the town, rather than slowly pump the area dry. But several people died inside their flooded homes.

It’s not clear to me from the news reports whether the levee overtopped from a wind- and pressure-driven storm surge or whether it overtopped from the sheer amount of rain that fell on the area, but in either case the slow-moving nature of Hurricane Isaac turned out to make the meager Category 1 hurricane into something much more horrific for some Lousiana communities. A reporter on the scene in Braithwaite described the eyewall, with the most intense winds and rain, stalling out in the area, but throughout its life Isaac was a fairly slow moving tropical cyclone. As it moved across Louisiana, its center was moving north about 9 miles per hour (14.5 km/hr). Typical hurricanes move about 15-20 mph (24-32 km/hr), and some can move up to 60 mph (96.5 km/hr).

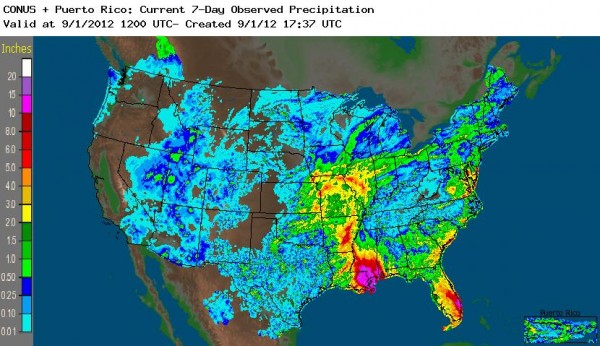

The problem with a slow-moving hurricane is that vast amount of precipitation can occur in the affected areas. In some parts of Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, and Florida more than 15 inches (380 mm) of rain have fallen in the last week. In New Orleans, the Hydrometeorological Prediction Center reports that 20.08 inches (510 mm). In the image below, you can also see the northward progression of the storm since making landfall.

NOAA's Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service (AHPS) map of rainfall accumulations for the week leading up to September 1, 2012.

All that water can lead to levee over-topping, like in Plaquemines Parish, and the risk of dam failures. Evacuations were ordered along the Tangipahoa River, which drains into Lake Pontchartrain, because of fears that Percy Quin Dam would fail. More than 50,000 people have been evacuated as the risk of dam failure or the need to intentionally breach the dam is still being evaluated. And, of course, while media attention (and this blog post, guilty as charged) focuses on the dramatic stories, there are many other areas in the Gulf Coast where flooding is on-going. Even as far north as Kansas City and southern Illinois, flood warnings are in effect.

Isaac is a good reminder why the primary cause of death in the US from tropical cyclones is from freshwater flooding. And it suggests that the single-minded focus on hurricane windspeeds may distract us from taking the flooding threat as seriously as we should. Those people who decided to stay in Plaquemines Parish because the Category 1 hurricane wouldn’t be that bad? When the interview was conducted, they were expressing their regret. The president-elect of the American Meteorological Society, J. Marshall Shepherd, wrote a blog post about the Lessons from Isaac, in which he suggested: “Is it time to consider an augmentation of the Saffir Simpson scale to capture the rainfall-flood threat? It is a difficult science problem, but probably one worth investigating. I also argue that our media colleagues must consider their coverage strategy and category “anticipation” or hype carefully.”

Nice plan for content warnings on Mastodon and the Fediverse. Now you need a Mastodon/Fediverse button on this blog.