Coals exposed along Stenkul Fiord, southern Ellesmere Island, Canadian High Arctic

(Photo by Anne Jefferson)

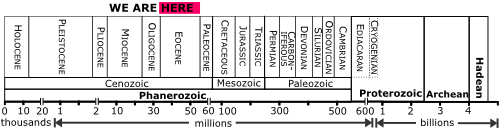

For more than 55 million years, Ellesmere Island remained in one place while the world around it changed. Fifty-five million years ago, verdant forests grew at 75¬? North latitude. These wetland forests, [comprised] of species now primarily found in China, grew on an alluvial plain where channels meandered back and forth and periodic floods buried stumps, logs, and leaves intact. Today the forests are preserved as coal seams that outcrop on the edges …[of] modern Ellesmere Island, [where] there are no forests, and the tallest vegetation grows less than 15 cm high. Large parts of the area are polar desert, subject to intensely cold and dark winters and minimal precipitation.

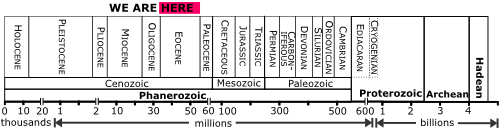

These are the opening lines to my M.S. thesis, in which I contrasted the Paleocene-Eocene and modern hydrological environments of Stenkul Fiord, on southern Ellesmere Island in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. My thesis goes on to describe a world that no longer exists, except in the fossil record preserved at sites in the High Arctic. This former world may provide clues as to how polar flora and fauna and their physical environment responded to global mean surface temperatures that were 2-4 degrees warmer than they are today, yet are right in line with the predictions for the end of this century. These clues, recorded in the fossil and stratigraphic record in coal and sediment layers on remote Ellesmere Island, well north of the northernmost civilian settlement in North America, are under attack. The same human demand for energy for that is driving up global temperatures is threatening to erase the very fossils that record polar life under a warmer temperature regime. The government of Canada’s Nunavut territory is currently considering claims by Westar Resources, Inc. to mine the coal beds in one of the most spectacular of all the fossil localities in the High Arctic.

During the Paleocene and Eocene, tropical vegetation extended to 50¬? N, and broad-leaved evergreens reached 70¬? N. There was no permanent polar ice, and large parts of the polar regions were covered by forests dominated by cypresses and angiosperms. Fossilized remnants of these forests are found in locations such as Spitsbergen, Greenland, the Yukon, northeastern Asia, and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. This widespread Arcto-Tertiary forest nearly disappeared as the climate cooled over the past 30 million years and modern temperate forests. Today the last remnants of this flora are preserved in the mountains of China’s Sichuan province.

Modern Metasequoia glyptostroboides. Photo taken at the Tyler Arboretum where it was identified. Photo (c)2006 Derek Ramsey via Wikimedia. (Click image for usage permissions)

Among the signature trees of the Arcto-Tertiary fossil record is the Metasequoia, a genus which was thought to have gone extinct in the Miocene until an isolated grove of Metasequoia glyptostroboides, or dawn redwood, was discovered in Sichuan in 1944. Metasequoia grows to 60 m tall and unlike sequoias, it is deciduous and loses its leaves in the winter. This would have been quite handy for life in the High Arctic, where in the Paleocene-Eocene winter temperatures might have hovered just above freezing, but would still have been dark for six months of the year.

At the site where I worked on Ellesmere Island, there were large Metasequoia logs and tree stumps still rooted in situ in the coal layers. Picking apart the coal layers, I could pull out Metasequoia leaves, twigs, and male and female cones. The siltstones between the coals preserved beautiful fossil impressions of a variety of tree leaves and stems.

Metasequoia log, Stenkul Fiord, Ellesmere Island (photo by Anne Jefferson)

Metasequoia stump in its growth position, Stenkul Fiord, Ellesmere Island

(photo by Anne Jefferson)

My field site on Stenkul Fiord yielded only plant fossils, and for now, is safe from the development plans of Westar Resources and the Nunavut government. But a bit north at Strathcona Fiord, plants are second fiddle to the best vertebrate fossil locality of the Canadian High Arctic. At Strathcona Fiord, the fossil record shows that those Eocene forests were inhabited by alligators, giant tortoises, primates, tapirs, and the hippo-like Coryphodon. There have been over 40 papers published on the Eocene fossils of Strathcona Fiord alone. It’s not just the Eocene that makes Strathcona Fiord an amazing fossil locality either. Pliocene layers at Strathcona Fiord have yielded plants, insects, mollusks, fish, frog and mammals such as black bear, 3-toed horse, beaver, and badger. It is the only known Pliocene Arctic site with vertebrate remains.

Strathcona Fiord is one of three sites where Westar Resources, Inc. plans to mine the coal. Mining the coal will permanently destroy the embedded fossils and the possibilities for any additional discoveries at this site. The other two Ellesmere Island areas in which Westar has applied for mining permits are the Fosheim and Bache Pennisulas. We don’t know as much about the paleontology of these areas, but the little work that has been done on the Fosheim Peninsula has already discovered Eocene leaf beds and Pliocene fossils.

Paleontologists and geologists around the world are raising their voices in opposition to the proposed coal mining at Strathcona Fiord and the other sites on Ellesmere Island. The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology has issued a press release expressing concern and urging the preservation of the fossils resources. There is also a coordinated letter-writing campaign to the Nunavut Impact Review Board. I’ve just sent a letter to the review board, which I’ve appended below. If you are a paleontologist, paleoclimatologist, geologist, Arctic lover, fossil lover, or otherwise moved by the incredible story of alligators and towering trees at 75° N, I urge you join me in writing to the government of Nunavut and encourage them to at least require more study of the localities before mining is approved. Letters can be sent electronically to info@nirb.ca.

To the members of the Nunavut Impact Review Board,

I appreciate the opportunity to write to you concerning the proposed Westar coal project on Ellesmere Island. I am a geologist at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, and my research focuses on the intersection of hydrology, landscapes, and climate. My graduate M.S. thesis research focused on the paleo-environments of the Eureka Sound Group exposed at Stenkul Fiord on southern Ellesmere Island. I used the coal and sediment layers, and the fossils they contain, to understand variability of hydrological environments that existed in the Arctic 55 million years ago. Today, I work on issues of water and modern climate change, but my perspective was profoundly influenced by the time I spent on Ellesmere Island walking amidst the coal layers and fossilized tree trunks.

The proposed activities by Westar Resources, Inc. could damage or destroy fossil sites that form an important part of Nunavut’s history and environmental legacy. These fossils tell us about the history of Arctic plants and animals, and they are recognized internationally for their scientific importance. They also provide important evidence from a time when Earth, especially the Arctic, was warmer. The fossils of the Ellesmere Island sites proposed for mining by Ellesmere Island provide clues as to how polar flora and fauna and their physical environment responded to global mean surface temperatures that were 2-4 degrees warmer than they are today, yet are right in line with the predictions for the end of this century. Ultimately, I hope that evidence from Nunavut’s fossil record can help us better estimate and prepare for future climate change.

If the fossil sites in the Westar coal project areas are destroyed the evidence is lost forever, therefore I recommend that the Nunavut Impact Review Board advise the Minister, pursuant to article 12.4.4(a) of the Nunavut Land Claim Agreement, that the project proposal requires review under Part 5 or 6. I believe that much more paleontological and paleoclimatic research can be conducted at these sites before any coal is extracted from them and we lose the opportunity to learn all that we can.

I thank you for your consideration, and request that you keep me informed of the results of this screening process.

![]() Today President Obama announced that in his next budget he was going to cut funding for NASA’s Constellation Program, and with it the plan to send people back to the Moon. This is no doubt going to lead to a lot of noisy protest; but I can’t help wondering if it isn’t the correct decision, because I was never entirely clear on what, exactly, they were going to do when they got back to the Moon beyond a “well, gee, we’re on the Moon!” and we managed that 40 years ago. In fact, the story of the Apollo program contains a salutary lesson about the consequences of gearing your space programme totally around the simple goal of reaching somewhere: once you’ve got there, that’s it.

Today President Obama announced that in his next budget he was going to cut funding for NASA’s Constellation Program, and with it the plan to send people back to the Moon. This is no doubt going to lead to a lot of noisy protest; but I can’t help wondering if it isn’t the correct decision, because I was never entirely clear on what, exactly, they were going to do when they got back to the Moon beyond a “well, gee, we’re on the Moon!” and we managed that 40 years ago. In fact, the story of the Apollo program contains a salutary lesson about the consequences of gearing your space programme totally around the simple goal of reaching somewhere: once you’ve got there, that’s it.

Nice plan for content warnings on Mastodon and the Fediverse. Now you need a Mastodon/Fediverse button on this blog.