![]() The biggest earthquake this week occurred on Tuesday in Western Pakistan. The USGS pegs it at Magnitude 7.2, with a depth of 68 km.

The biggest earthquake this week occurred on Tuesday in Western Pakistan. The USGS pegs it at Magnitude 7.2, with a depth of 68 km.

The rupture (big yellow dot) occurred at ~70 km depth beneath western Pakistan, close to Afghan and Iranian borders

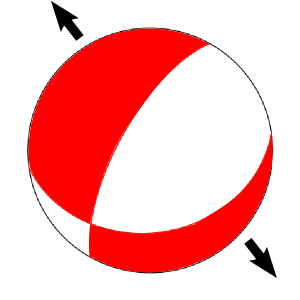

The focal mechanism indicates that this rupture was due to extension in a northwest-southeast direction (for the puzzled, here’s a primer on earthquake beach balls).

This seems quite odd at first, since we are clearly in a region of plate convergence. The Himalayas and Tibetan plateau to the northeast are perhaps the most dramatic expression of the ongoing collision of India (and, to the west, Arabia) with Eurasia, but even in western Pakistan the topography is dominated by a prominent curved fold and thrust belt (which appears to be a substantial control of the course of the Indus river to the east).

Close up of fold and thrust belts in Western Pakistan - the faulting that formed these is too shallow to be associated with the earthquake.

However, look again at the depth of the earthquake. Depending on the algorithm and the types of seismic waves used in the calculation, the estimated rupture depth varied between about 50 and 80 km. This was quite fortunate for the Pakistanis still trying to recover from last year’s devastating flooding: although the earthquake was released twice as much energy as the recent events in Haiti and Christchurch did, seismic energy spreads out and dissipates the longer it travels through the solid earth, so there was only mild (if widespread) shaking at the surface.

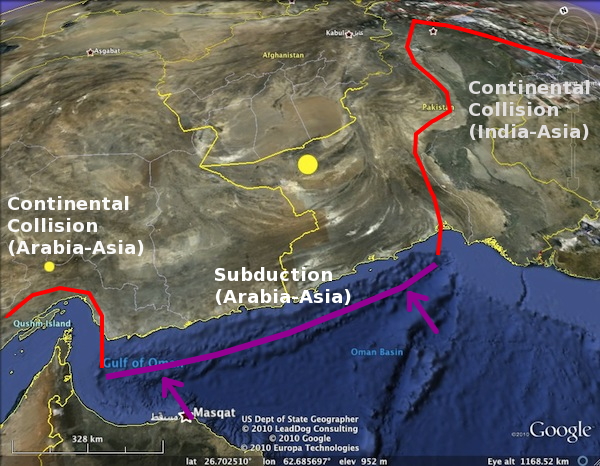

So this earthquake occurred a long way below the crust being deformed by thrust faulting in this area – in fact, it almost certainly occurred deeper in the Earth than the crust in this region is thick. However, the plate boundary in this particular region is rather interesting, because of the presence of the Makran trench just off coast to the south. This marks the position of a narrow subduction zone, hemmed in on either side by areas of colliding continental crust, where oceanic crust is being thrust down into the mantle.

The Makran Subduction zone, sandwiched between two areas of continental collision.

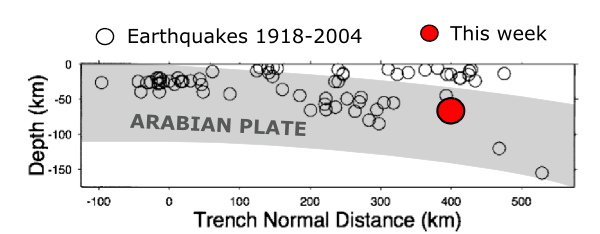

This means that there is a subducted slab dipping beneath western Pakistan. Data on its shape and extent are rather sparse – the nexus of Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan is not really a place you can just wander into and deploy a local seismometer network. However, I did manage to dig up a paper that plots the location of earthquakes large enough to be picked up by the global seismometer network. The deeper earthquakes in this dataset trace out a zone of seismic activity that gradually dips northwards beneath western Pakistan, which Tuesday’s earthquake also appears to fall within.

Rough shape of the subducting Arabian plate (shading added by me) based on the earthquake locations of Enghdal et al. (2006), compared to the location of this week's M7.2 quake.

It seems most likely then, that this earthquake was a rupture in the subducted Arabian plate. Extensional earthquakes are not uncommon in subducting slabs; the weight of already subducted material deeper in the mantle can exert a fairly substantial pulling force, causing the shallower parts of the slab to stretch. In this particular case, the direction of extension is not quite in the northerly, down-dip direction you would expect from ‘slab pull’, but the narrowness of the subduction zone, and its position sandwiched between two areas of colliding and thickening continental crust, may have complicated the forces at work.

![CropperCapture[1] Hydrographs of Hood and Sandy Rivers for flood of January 15-16, 2011 (Data from USGS)](https://all-geo.org/highlyallochthonous/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/CropperCapture1.jpg)

![CropperCapture[3] 2011 flood hydrographs in comparison to 2006, 1996, and 1964 peak flows for the Hood and Sandy Rivers, Oregon (USGS data)](https://all-geo.org/highlyallochthonous/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/CropperCapture3.jpg)

Nice plan for content warnings on Mastodon and the Fediverse. Now you need a Mastodon/Fediverse button on this blog.