![]()

![]()

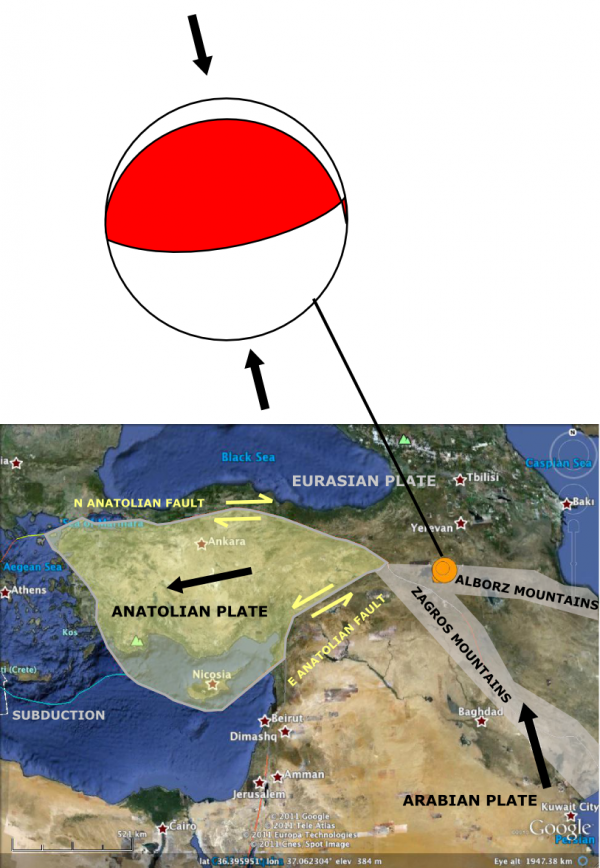

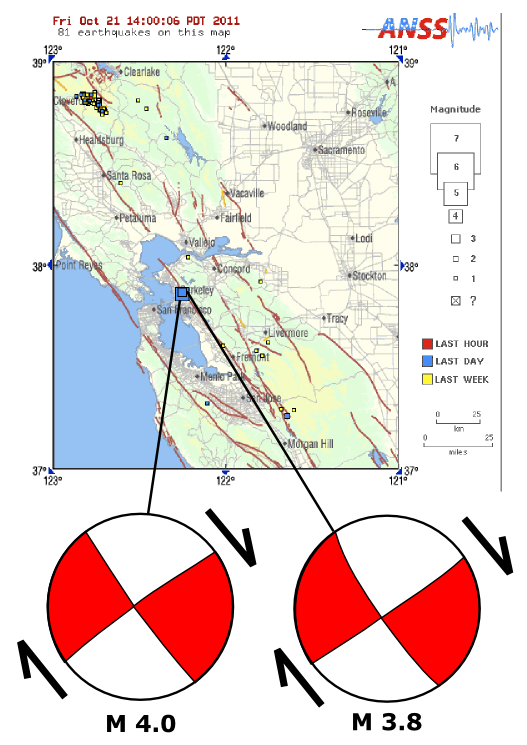

Earthquakes

The big news this week was the magnitude 7.2 earthquake in eastern Turkey, which I blogged about here and expanded on in a post on the Scientific American Guest Blog. Some other useful links and resources:

- Nice post on the seismic history of the Van region, Turkey, by David Bressan

http://historyofgeology.fieldofscience.com/2011/10/paleoseismology-of-anatolian-and.html

(via @Fitzgabbro) - In Focus shows aftermath of Ercis quake. Lots of concrete & block construction, not much rebar.

http://www.theatlantic.com/infocus/2011/10/deadly-earthquake-in-turkey/100177/

(via @lockwooddewitt) - Amid Debris in Turkey, Survivors & Signs of Poor Construction (questions raised about quality of construction material)

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/26/world/europe/death-toll-in-turkey-quake-rises-as-rescuers-race-to-find-trapped-survivors.html

(via @CPPGeophysics) - Dot Earth Blog: Ideas for Spreading Quake-Resistent Building Methods

http://dotearth.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/10/29/ideas-for-spreading-quake-resistent-building-methods/

(via @nytimesscience)

Volcanoes

- Some cool pictures of the ongoing El Hierro undersea eruption’s effect on the sea at National Geographic.

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2011/10/pictures/111019-underwater-volcano-spain-canary-islands-science-travel/

(via @NatGeo, @rivrchik) - So

basically, we should be drilling geothermal wells instead of fracking? : geothermal map of U.S.

http://www.smu.edu/News/2011/geothermal-24oct2011.aspx

(via @clasticdetritus)

Fossils

- Paleontologists think the T-rex is ‘frikking weird’. I think it’s a compliment…

http://archosaurmusings.wordpress.com/2011/10/19/guest-post-love-the-tyrant-not-the-hype/ - Jurassic Park is almost 20 years old, but we still love it. Brian Switek have a few thoughts as to why:

http://blogs.smithsonianmag.com/dinosaur/2011/10/why-do-we-keep-going-back-to-jurassic-park/

Planets

- Science from Vesta from Geological Society of America meeting: Vesta has 2 basins & sets of troughs

http://www.planetary.org/blog/article/00003233/

(by @elakdawalla)

(Paleo)climate

- Informative commentary on the Muller/BEST affair at RealClimate admirably reins in the possible snark, especially when you compare it to my own reaction.

http://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2011/10/berkeley-earthquake-called-off/

(via @MichaelEMann) - The Daily Show’s spin on this is also awesome: Is science a scam?

http://www.thedailyshow.com/watch/wed-october-26-2011/weathering-fights—science—what-s-it-up-to-

(via @Colo_kea)The Daily Show With Jon Stewart Mon – Thurs 11p / 10c Weathering Fights – Science: What’s It Up To? Daily Show Full Episodes Political Humor & Satire Blog The Daily Show on Facebook - Survey claims 72 % approval of research into geoengineering; much smaller % seem to know what geoengineering means…

http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2011-10/iop-sfp102111.php

Water (floods)

- A rather scary satellite image of the floods around Bangkok. It’s practically an island.

http://www.forbes.com/sites/simonmontlake/2011/10/25/bangkoks-precarious-plumbing-a-visual-guide/ - Thousands Leave Bangkok as Flooding Spreads:

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/28/world/asia/thousands-leave-bangkok-as-flooding-spreads.html

(via @revkin) - A Few Good Reads: Bangkok Flood Update Edition(10/24/11)

http://ayresriverblog.com/2011/10/24/a-few-good-reads-102411/

(via @DustyWRobinson) - Date Petley provides an update on the Burma flood and riverbank collapse disaster

http://blogs.agu.org/landslideblog/2011/10/24/update-on-the-burma-flood-and-riverbank-collapse-disaster/

(via @Geoblogfeed) - Floods in Cambodia from @NASA_EO

http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=76212 - Flooding in southeastern Mexico from @NASA_EO #NASA

http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=76216 - Flood complacency evaporates in Bangkok –

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-pacific-15435286

Environmental

- “Population is the issue you blame if you can’t admit to your own impacts”

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/georgemonbiot/2011/oct/27/population-consumption-threat-to-planet

(via @jfleck, @alicebell) - Goods vs Commodities: or why oil companies can be faulted for much, but not the price of oil.

http://earth-likeplanet.blogspot.com/2011/10/goods-vs-commodities-why-shell-exxon.html - So sad. The Nautilus: immensely beautiful, last living close relatives of ammonites, and severely endangered.

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/25/science/25nautilus.html

(via @mmvk) - Campaigners occupy Belo Monte dam –

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-15487852

General Geology

- Fantastic post from @kuchtam on teaching and playing with the EmRiver stream table

http://pascals-puppy.blogspot.com/2011/10/transformative-works-at-intersection-of.html

(via @clasticdetritus) - Excellent post from @glacial_till on Deep Time, complete with Dr Who and radioactively decaying Daleks…

http://glacialtill.wordpress.com/2011/10/24/geology-101-deep-time-or-geologists-as-time-lords/ - Callan Bentley pointed out this epically awesome structural geology teaching tool. Drool.

http://visible-geology.appspot.com/ - Geology outcrops in the most unlikely places: including, @metageologist has found, the toilets of posh office buildings

http://all-geo.org/metageologist/2011/10/sediments-and-shiny-shoes/ - Spectacular video of rockfall onto Franz Josef glacier in New Zealand: Lucky escape for tourists.

http://blogs.agu.org/landslideblog/2011/10/27/spectacular-rockfall-video-on-the-franz-josef-glacier-a-lucky-escape-for-a-tour-party/

(via @davepetley) - Strained metaconglomerate photos by Callan Bentley a fabulous example of how rocks flow like putty when deep/hot enough.

http://blogs.agu.org/mountainbeltway/2011/10/26/strained-timiskaming/

Interesting Miscellaney

- Great points from Brian Romans on why he won’t blog unpublished results, building on a Twitter discussion in response to an article in the Guardian.

http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2011/10/why-i-wont-blog-unpublished-results/ - Great BBC interview with Jocelyn Bell on discovering pulsars, challenges of being a women in science

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b016812j#synopsis

(via @lockwooddewitt) - Remember Ben Goldacre’s latest column every time the phrase ‘postcode lottery’ comes up in the headlines.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/oct/28/bad-science-diy-data-analysis - Not ruin. Make 1000x more AWESOME!! Another Thing Sonic Screwdrivers Can Do: Ruin Action Movies

http://www.themarysue.com/sonic-screwdrivers-action-movies/

(via @JenLucPiquant) - Guy who helped design iPod leaves Apple to build… an iThermostat. Easy to use, learns your routine, helps save energy.

http://www.nest.com/living-with-nest/index.html

Nice plan for content warnings on Mastodon and the Fediverse. Now you need a Mastodon/Fediverse button on this blog.