![]() If you live in the eastern 1/3 of the US and you haven’t started paying attention to Hurricane Sandy, today is THE day. This odd late-season storm is going to hit the northeastern and mid-Atlantic coast hard, having already stormed across the Caribbean, killing at least 48 people.

If you live in the eastern 1/3 of the US and you haven’t started paying attention to Hurricane Sandy, today is THE day. This odd late-season storm is going to hit the northeastern and mid-Atlantic coast hard, having already stormed across the Caribbean, killing at least 48 people.

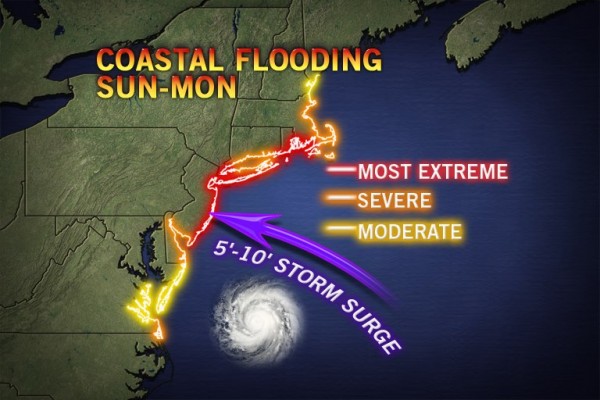

Accuweather map of predicted storm surges along the east coast. Click image for source. Note: I had a hard time finding both a detailed and quantitative map of predicted surges. If anyone knows of a better map, please let me know in the comments.

Much like we saw with Isaac earlier this year, the damage in slow-moving and relatively weak hurricanes (Sandy is a Category 1 currently) comes from all of the water in inland flooding and from the storm surge along the coast. When Sandy hits shore someplace between Delaware and New York City on Monday night, the storm surge is expected to be especially fearsome. As Ben Strauss at Climate Central explains:

- Sandy is projected to create tall storm surges, due to an enormous wind field influencing wide areas of ocean.

- The surge may be prolonged, due to the storm’s large size and slow movement. This means many areas will experience surge combined with at least one high tide.

- With a full moon near, tides are running high to begin with.

- Rivers swollen by significant rainfall may compound tides and surge locally.

- Sea level rise over the past century has raised the launch pad for storms and tides to begin with, by more than a foot across most of the Mid-Atlantic. Sinking land has driven part of this rise, but global warming, which melts glaciers and expands ocean water by heating it, appears to be the dominant factor across much of the region.

In Sandy’s path, as with Irene last year, lies the densely populated east coast. Which is why knowledgeable people are now talking about Sandy as likely to be a multi-billion dollar disaster. Jeff Masters of Weather Underground estimates that there could be as much as a billion dollars of wind damages and associated power losses, with flooding costing another billion in losses, and if the New York City transit system floods losses could run into the tens of billions.

And all of that is just the hurricane. Added on top of that is the potential convergence of the hurricane with a very deep upper-level trough over the central U.S. and unusually strong high-latitude blocking. Blocking occurs when a high pressure dome stays in the same place for several days or longer, blocking eastern flow of the polar jet stream, producing “seemingly endless stretches” of the same weather, and pushing storms far off their usual tracks. As explained by Will Komaromi of the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science at the University of Miami:

“Normally a hurricane weakens as it moves northward, as it encounters an increasingly unfavorable environment. This means greater wind shear, drier air, and lower sea surface temperatures. However, with phasing [convergence] events, the tropical system merges with the mid-latitude system in such a way that baroclinic instability (arising from sharp air temperature/density gradients) and extremely divergent air at the upper-levels more than compensates for a decreasingly favorable environment for tropical systems.”

Komaromi goes on to explain that the Atlantic Gulf Stream is unusually warm for this time of year, allowing Sandy to remain stronger than it might have while out to see. Also, the extra strong blocking over the North Atlantic will mean that the hurricane moves very slowly and the storm will track farther west over the US rather than curving out to the mid-ocean. Komaromi shows that this is extremely similar to the 1991 “Perfect Storm”, subject of the book and movie of the same name.

The fallout of all this meteorological fury is likely to be felt both at the coast and far inland. The quantitative precipitation forecast for NOAA for the next five days shows eight states with areas expected to receive more than 4 inches (101 mm) of precipitation. Far more unusual than lots of rain is the possibility that Sandy will be a “snow-i-cane” dumping up to 12 inches (304 mm) of snow in the mountains of Virginia and West Virginia, and possibly into Tennessee and North Carolina. With leaves still on the trees in southern and coastal regions, the wind, rain, and snow will play havoc with above ground power lines. Widespread power outages are considered likely all the way into western Pennsylvania, New York, and West Virginia. Even in Ohio, my area is considered in the “possible” zone for power failures.

NOAA’s Hydrometeorological Prediction Service quantitative precipitation forecast for the next 5 days. Click image for more information.

In addition to watching the weather and taking the necessary steps to prepare ourselves for whatever blows our way, a small group of scientists will be collecting precipitation samples for isotopic analyses by Gabe Bowen’s group at the University of Utah. If you live in the area affected by Sandy and want to help collect precipitation, look for more information here. I’ve already gotten 1.2 inches (30 mm) of rain since yesterday afternoon, and we’re not even seeing the storm effects yet. I’m likely to get another 4 inches (100 mm) by Thursday.

A somewhat larger group of geoscientists will be working on their posters and talks while hoping to avoid power outages and travel delays that could scuttle plans to attend the Geological Society of America meeting in Charlotte, North Carolina. Charlotte is not at all in the storm’s path, so if we can get there, everything should be fine.* I’m hopeful that the freeways will be open through West Virginia by Friday night, when I’ll drive south to convene two sessions, lead a field trip, and present a poster. But I worry for colleagues in the full brunt of the storm and hope that they have both adequate time to prepare for and attend the meeting. I’m also crossing my fingers that virtually all infrastructure is functioning again by Tuesday, November 6th, and that everyone affected by the storm will be able to cast their votes in a very important election.

As I contemplate coming events, I find the song “Storm Comin'” by The Wailing Jennys has been playing in my head almost constantly. I love how it captures the tension and anticipation of a storm rolling towards you across the plains or ocean.** Unfortunately, I wouldn’t recommend following this advice for emergency preparedness, instead you should take a make an emergency kit along the lines of this one and pay attention to watches, warnings, and evacuations in your area. Be safe everyone.

The Wailing Jennys perform their song "Storm Comin'"

*Disclaimer here about being neither a meteorologist nor a disaster recovery expert, so don’t take my word as a guarantee. Also I’m glad I’m not in Italy.

**For me, music is poetry, so consider this my entry from the upcoming Accretionary Wedge carnvial on geo-poetry.

Nice plan for content warnings on Mastodon and the Fediverse. Now you need a Mastodon/Fediverse button on this blog.