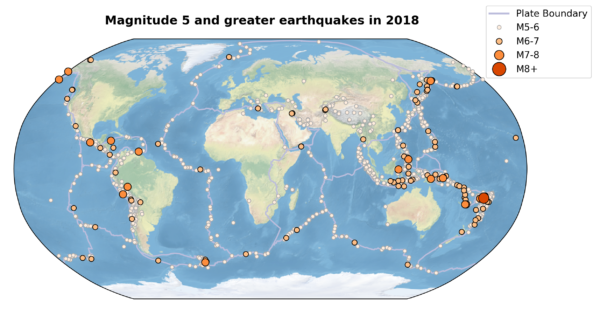

Just as I did in 2016 and 2017, I thought I’d begin the new year with a look back at the earthquake activity in the last. According to the catalogue maintained by the USGS, the Earth’s ever-grinding tectonic plates produced 1,795 earthquakes of magnitude 5 or greater over the past 12 months. Below are maps of the individual locations of each of these earthquakes, as well as a global seismic ‘heat map’, scaled to represented the total energy release in each 5º grid square.

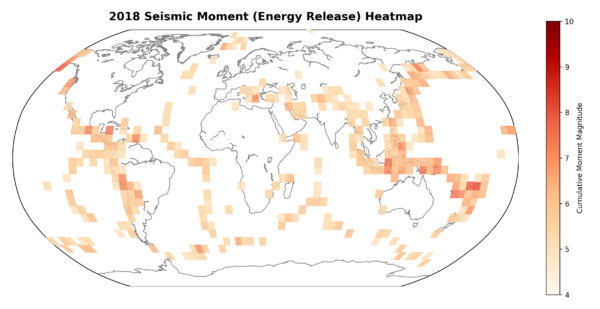

Heat Map of global seismic activity in 2018, scaled to total moment release from all M5+ earthquakes in each 5º grid square

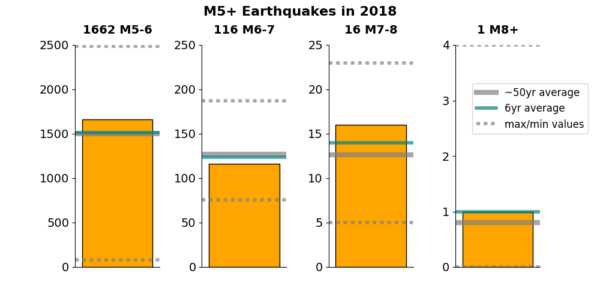

Based on the last 50 years or so of data from the global network of seismometers, in an average year we expect around 1500 magnitude 5-6 earthquakes; about 130 magnitude 6-7 earthquakes, about a dozen magnitude 7-8 earthquakes, and maybe one event larger than magnitude 8 (earthquakes of magnitude 9 or more are much rarer beasts, with only two so far in the 21st century). 2018 boasted about 10% more M5-6 earthquakes than the long-term average, about 10% less M6-7 earthquakes, and about 20% (2-3) more M7-8 events and that one M8+ event. All this is well within the variability we see between years in the records since 1974.

Number of earthquakes in different magnitude ranges in 2018, compared to longer term averages and ranges.

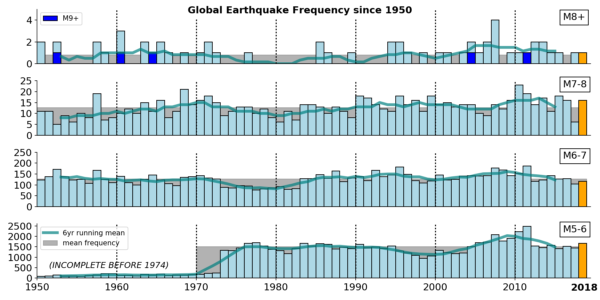

2018 earthquake frequency compared to the instrumental record since 1950 (note that M5-6 events are largely missing from the catalogue prior to the 1970s).

So, from the global perspective, an entirely ‘normal’ seismic year. When discussing earthquake prediction earlier this year, I argued:

In a geological echo of the uncertainty principle, we can only narrow down the location of a future earthquake if we are very fuzzy about the timeframe over which it will occur, and we can only talk with any confidence about a specific period in which an earthquake of a particular size will occur by greatly expanding the area of the planet we are considering.

The same principle applies when talking about multiple earthquakes. The scale of the whole planet, and the timescale of a year, is fuzzy enough to ‘predict’ roughly how many earthquakes of particular sizes are going to happen. But the characteristics of each individual earthquake – when and particularly where – are not predictable. Yes, we got the expected magnitude 8+ earthquake, but it was almost 600 km down in the subducting Pacific slab beneath Fiji, deep enough that it only caused minor shaking on the surface and no damage.

Contrast this with the magnitude 7.5 Palu earthquake. It released less than a tenth of the energy, but the rupture occurred within 20 km of the surface. The strong ground shaking that resulted, and particularly the landslides and tsunami that the shaking triggered, killed at least 2 thousand people, making it by far the deadliest earthquake of the year. Also in unfortunate Indonesia, a sequence of magnitude 6-7 earthquakes beneath Lombok Island in August killed hundreds, when most of the dozens of others in this size range that occurred last year were, through some combination of less proximity to the surface or people and more resilient infrastructure, little more than an inconvenience. Last month’s Anchorage earthquake springs to mind. And one of those more than 1600 magnitude 5-6 earthquakes was sufficient to kill 14 people in Haiti. Even if an earthquake only severely shakes a very small area, that small area can coincide with vulnerable people.

As always, earthquake location matters. In the year ahead, we can expect roughly the same numbers of earthquakes to happen globally as in the past. But their locations and depths and timing – the factors that, far more than magnitude, tip the balance between a minor blip and a disaster – will sadly only unfold as the year itself does.

Nice plan for content warnings on Mastodon and the Fediverse. Now you need a Mastodon/Fediverse button on this blog.