As Steinn reported at the time, last Thursday Iceland was shaken by a magnitude 6.3 earthquake (Ole has more). Here’s the USGS moment tensor solution:

The pattern of first motions indicates a strike-slip earthquake, where the two sides of an almost vertical fault are moving past each other. This wasn’t actually what I was expecting when I clicked through to the USGS report. Iceland, after all, is basically just a particularly volcanic part of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, which marks the extensional plate boundary between the North American and Eurasian plates. Western Iceland, which is on the North American plate, and eastern Iceland, which is part of the Eurasian plate, are moving away from each other at about the speed that your fingernails grow; as such, I was expecting to see an extensional earthquake mechanism. So why do we have such a large strike-slip earthquake occuring within a rift zone? The answer can be found by zooming in a bit on Iceland, to see exactly where the earthquake occurs:

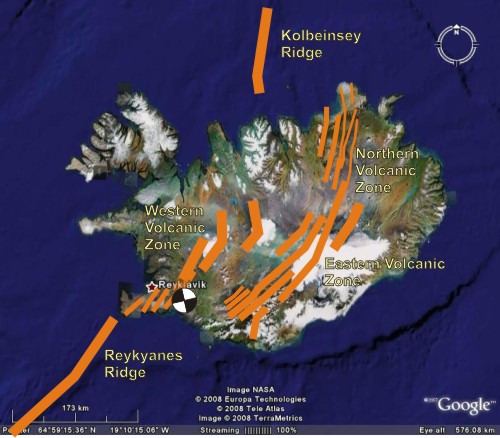

This shows that the plate boundary through Iceland is not a single, linear rift zone. As the Reykyanes Ridge, the segment of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge south of Iceland, reaches the coast, it continues as the Western Volcanic Zone, but fairly quickly dies out as the zone of maximum volcanic activity jumps eastward to the Eastern and Northern Volcanic Zones. From its location, last week’s earthquake is related to this offset.

When the mid-ocean ridges were first mapped in detail in the 1950s, similar offsets (also referred to as fracture zones) were found to be quite common, as you can see from this view of Central Atlantic bathymetry.

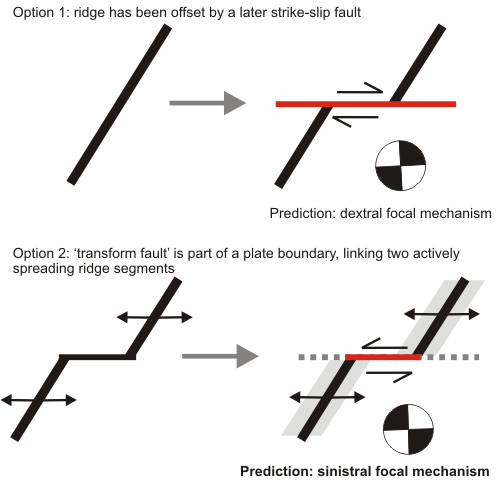

Initially, it was assumed that they represented faults which had chopped up an originally linear ridge. But as the evidence stacked up that new oceanic crust was being actively created at the mid-ocean ridges, Tuzo Wilson suggested that rather than being two superimposed tectonic features within a deforming region of the Earth’s crust, the rifting segments and the fracture zones were all part of the same system, separating rigid crustal blocks that were moving apart from each other. The key point about this nifty idea was that it could be tested; it predicted opposite senses of motion on the fracture zones. Going back to the rift offset we see in southern Iceland, if it is due to a conventional strike slip faulting disrupting an originally linear feature, then the sense of motion will be dextral (basically, if you’re looking across the the other side of a fault as it moves in an earthquake, the ground moves to the right); if it is a ‘transform fault’ that links two spreading centres, then the sense of motion will be sinistral (the ground on the other side of the fault moves left).

Hopefully, you can see that the focal mechanism of last week’s earthquake is indeed sinistral; this suggests that the offset that it is associated with is indeed a transform zone of an extensional plate boundary. Just as it was 40 years ago, seismological evidence remains a powerful tool for demonstrating the predictive power of plate tectonics.

Comments (3)

Links (1)-

Pingback: Friday Focal Mechanism | Highly Allochthonous