![]() In the early hours of 13 April 1992, the border region in western Europe where Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands meet was shaken by a magnitude 5.4 earthquake, caused by northeast-southwest extension in the Roer Valley Graben. The shaking was severe enough to damage buildings 30-40 kilometres from the epicentre. 40 kilometres to the south, in the small town of Valkenburg, a group of British schoolchildren on a European excursion were sleeping peacefully in their beds, a 13 year-young version of this geoblogger amongst their number.

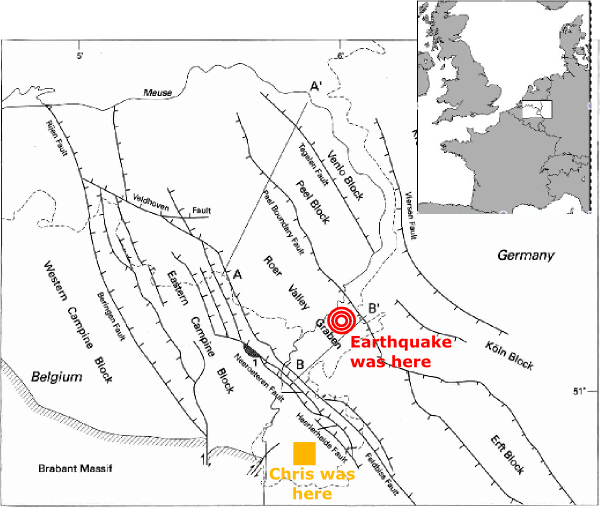

In the early hours of 13 April 1992, the border region in western Europe where Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands meet was shaken by a magnitude 5.4 earthquake, caused by northeast-southwest extension in the Roer Valley Graben. The shaking was severe enough to damage buildings 30-40 kilometres from the epicentre. 40 kilometres to the south, in the small town of Valkenburg, a group of British schoolchildren on a European excursion were sleeping peacefully in their beds, a 13 year-young version of this geoblogger amongst their number.

Location of the Roermond earthquake on 13th April 1992; location of Chris on 13th April 1992. Source for map: Geluk et al. 1994 (click for pdf).

I distinctly remember waking up to the room shaking and (rather woozily) thinking, “Earthquake!” But I also distinctly remember then thinking, “You don’t get earthquakes in the Netherlands. I must be dreaming,” before turning over and going back to sleep. Imagine my surprise the next morning when I discovered that not only had everyone else in our hotel shared my “dream”, but that the shaking had been strong enough to toss some of them from their beds. And that is how I semi-slept through what remains my only up close and personal encounter with the tectonic forces that shape our planet: forces that I would end up studying for a living, little did I know it at the time.

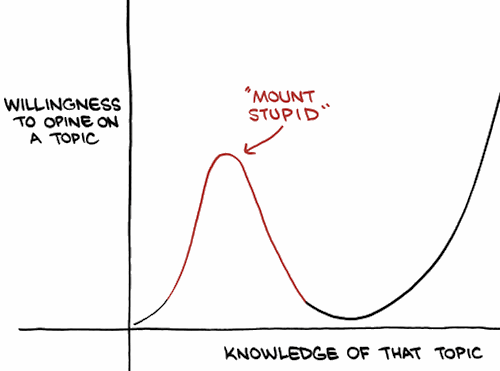

I normally tell this story for humourous effect, but a part of me always cringes a little inside when I recall these events, because it also illustrates how, despite me already having ambitions to become a scientist at this age, I was still a long way from thinking like a scientist. Firstly, I assumed in the arrogance of precocious youth that I already knew everything worth knowing about earthquakes. I had read that earthquakes were associated with the boundaries of tectonic plates, and I also knew that the Netherlands was nowhere near such a boundary. I had read nothing, or at least remembered nothing, about the earthquakes that occur within plates, but I wasn’t yet mature enough to realise how much I didn’t know.

Perhaps 'Mount Unknowingly Ignorant' would be more accurate. Source: Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal (click for full comic).

Perhaps more seriously, when confronted with a contradiction between what I thought I knew and actual reality, I responded with reflexive denial rather than curiousity. Even if it was 100% established that earthquakes only ever occurred at plate boundaries, a true scientist would not respond to an apparent earthquake in the Netherlands with a cry of “that’s impossible!’ A true scientist would think “hmmm, that’s funny…” and start investigating.

Narrative causality would demand that I close this story by telling you that not only did realising my mistake the next morning set me on the path to developing a proper scientific mindset, but also that it inspired me to take an interest in geology and tectonics. Sadly, neither is true. It took a few much more painful lessons before I became properly humble about my knowledge of the world; and before I learnt to stop bending the world to fit my preconceived notions, and actually observe and think more carefully about what was going on around me. And although I can’t completely rule out some subconcious effect of the Roermond earthquake on my later career choices, it took me at least six more years before I truly discovered the wonders of geology.

Now I know better than to dismiss the earthquake potential of places like central Europe. The Netherlands might be a long way from a true plate boundary, but there is a historical earthquake record going back centuries in this region, and paleoseismic studies following the 1992 earthquake found several fault scarps in the area with signs of Quarternary displacement. The Atlantic coast of the US has recently been described as a ‘passive-aggressive’ margin, hosting faults that can build up significant elastic strain over centuries and millenia before rupturing in earthquakes that could reach magnitude 7. Likewise, its European counterpart is not without its seismic dangers.

Corrective note: This post title originally referred to me sleeping through the ‘largest European earthquake in 200 years’. I think I originally meant to write ‘one of the largest’, but even then that’s a bit of an over-reach if you’re including Italy and Greece’. The title has now been appropriately modified.

This post was written in response to Ron Schott’s Accretionary Wedge call for stories of the most memorable or significant geologic event that we’ve directly experienced. Even if I sort of slept through it, I should at least get partial credit, right?

Nice plan for content warnings on Mastodon and the Fediverse. Now you need a Mastodon/Fediverse button on this blog.