There’s nothing particularly deterministic about starting a new year on January 1st. Our wall calendars happen to do so because of the circumstances of history. For hydrologists in the northern hemisphere, January 1st is not a great time to declare one year dead and a new one born. So instead, we transition between years on the 1st day of October. October 1st, 2012 marks day 1 of the 2013 water year. But, why?

There’s nothing particularly deterministic about starting a new year on January 1st. Our wall calendars happen to do so because of the circumstances of history. For hydrologists in the northern hemisphere, January 1st is not a great time to declare one year dead and a new one born. So instead, we transition between years on the 1st day of October. October 1st, 2012 marks day 1 of the 2013 water year. But, why?

The Upper Cuyahoga River as it might look about the time of the new water year. Photo by Ohio DNR (click image for source). A 40 km section upstream of Kent is a state scenic river and I really want to canoe it.

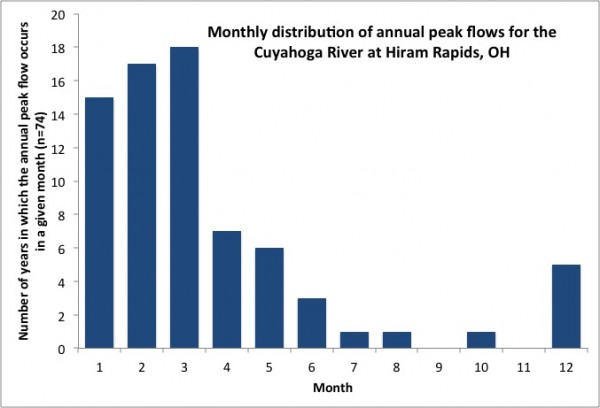

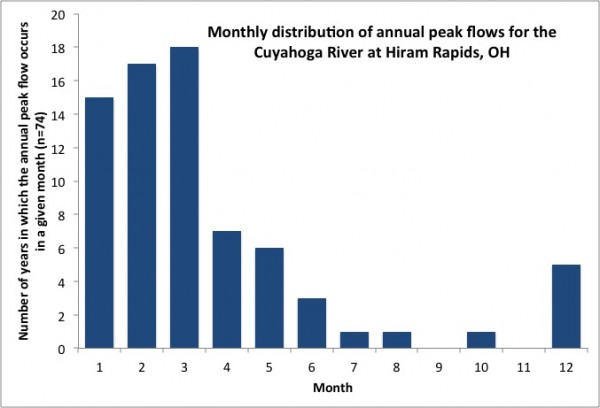

Many hydrologic analyses involve calculating statistics on an annual basis. We might want to calculate annual streamflow to determine how much drier 2012 was than 2011. Or we might want to look for trends in the size of floods. For the example of flood statistics, the most common way to get a time series of floods is to identify the largest flood occurring in each year. This “annual peak flow” record is then used within the framework of a probability distribution function to assign a probability of given size flood occurring in any one year. (Problematically, this has been called a “flood frequency distribution”, leading to unnecessary confusion on the part of the public, but I digress…)

We use only the largest flow each year to calculate statistics because it avoids statistical complication. Principally, we want to ensure all of our events are independent of each other. Let’s say there are two days with really high flows in a year. The highest flow is 27.8 m3/s and the second flow is 24.1 m3/s. If the first measurement was made on January 29th and the second one was from March 18th, then these two data are independent (i.e., not the same flood). But if one is from January 29th and the other is January 30th, they are clearly not independent and should not both be used to calculate statistics as if they were. So, we try to avoid this dependence issue by using only the largest flow each year.

Here’s where we come back to the idea of the water year. Let’s use an example from my local stream gage – the Cuyahoga River at Hiram Rapids. There was a big flood on December 31st, 1990 – the biggest flood of the whole year – reaching a peak flow of 71.4 m3/s. On January 1st, 1991 the water was still high – 66.8 m3/s. After that excitement, the rest of 1991 was pretty dry and flow never again gets anywhere near as high, peaking at 25.0 m3/s in early March. How do we calculate the statistics? If we used the calendar year as our basis, we’d end up double counting that late December flood and we’d throw our flood statistics off.

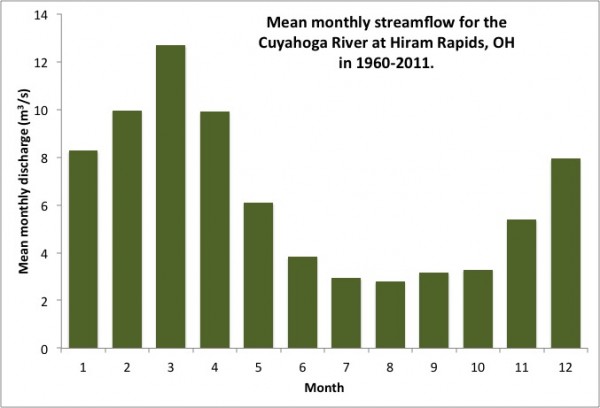

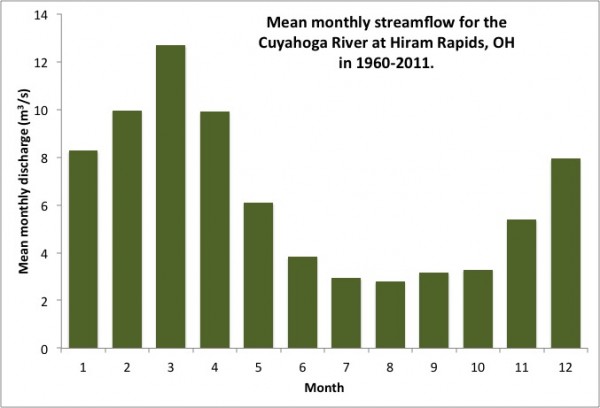

Instead, hydrologists use October 1st as our cut-off date. In many parts of the Northern Hemisphere, summer is a period of low streamflow, driven by strong evapotranspiration and atmospheric circulation patterns. (A prominent exception to the lack of summer flooding is when tropical cyclones make landfall.) In winter, rain-on-snow can produce large floods in some regions, while decreased evapotranspiration and more frontal storms increase the chances of flooding in some southern regions. In the spring, seasonal snowmelt produces flooding in northern and alpine regions. That leaves the autumn as the period least likely to have frequent flooding. Also, because evapotranspiration is subsiding with cooler temperatures, soil moisture and stream flow don’t tend to be recovering from their low points in the summer. So autumn is a time of transition and a time when extremes are unlikely. The graphs below illustrate this for my local stream gage, but similarly shaped distributions would likely exist for many other gages in the US and beyond.

Thus, it’s a perfect time of year to the clear the books and declare a new year for hydrologic statistics. And it’s got as much or more physical rationale than when we change the calendar on the wall. Happy New Water Year Everyone!

USGS data on annual peak flows for the Cuyahoga River at Hiram Rapids (gage #04202000) illustrates that summer and fall have the least frequent big floods.

Mean monthly discharge for the Cuyahoga River at Hiram Rapids shows that summer is the period of lowest flow and that by September and October average discharge is starting to increase.

![]() Today is the second day of the 2012 DonorsChoose Science Bloggers for Students challenge. It’s also Earth Science Week, with this year’s theme “Discovering Careers in the Earth Sciences.” Today, in particular, is “No Child Left Inside Day.” Finally, it’s Ada Lovelace Day, for celebrating the achievements of women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. So there can be no more appropriate day to contemplate who inspired us to love the Earth (sciences) and how we can help the next generation find their own inspiration and education.

Today is the second day of the 2012 DonorsChoose Science Bloggers for Students challenge. It’s also Earth Science Week, with this year’s theme “Discovering Careers in the Earth Sciences.” Today, in particular, is “No Child Left Inside Day.” Finally, it’s Ada Lovelace Day, for celebrating the achievements of women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. So there can be no more appropriate day to contemplate who inspired us to love the Earth (sciences) and how we can help the next generation find their own inspiration and education.

Nice plan for content warnings on Mastodon and the Fediverse. Now you need a Mastodon/Fediverse button on this blog.