![]()

![]() A busy week for both of us this week – Anne had a stimulating few days at the ScienceOnline 2013 conference in North Carolina, while Chris tried to achieve something other than teaching prep. But, through all this, we still found some cool links to share with y’all.

A busy week for both of us this week – Anne had a stimulating few days at the ScienceOnline 2013 conference in North Carolina, while Chris tried to achieve something other than teaching prep. But, through all this, we still found some cool links to share with y’all.

Up-Goer 5

-

The Up-Goer 5 challenge continues apace, with Ten Hundred Words of Science reaching more than 300 submissions to date. We’re also now on Twitter as @Ten100words, and on Facebook

- Chris wrote about the challenge at the Scientific American Guest Blog:

http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/2013/01/27/science-in-ten-hundred-words-the-up-goer-five-challenge/ - Lisa Grossman also blogged for New Scientist about the challenge:

http://www.newscientist.com/blogs/culturelab/2013/01/up-goer-five.html - When people say science has impenetrable jargon, I wonder if they’ve recently been to an art gallery…do we need a ‘Ten Hundred words of Art?’

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2013/jan/27/users-guide-international-art-english

(via @edyong209, @tomstandage)

Volcanoes

- Nice post from Erik Klemetti highlighting how molten lava is much more viscous than you might think.

http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2013/01/sampling-lava-tolbachik-eruption/

The video of Tolbachik lava flows that he’s referring to is pretty cool.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/earthvideo/9832045/Rare-glimpse-of-volcanic-activity-on-remote-Kamchatka-peninsula.html - Sea-floor spreading, on land: good stuff from David Pyle on research into rifting processed in Afar, Ethiopia

http://volcanicdegassing.wordpress.com/2013/02/01/sea-floor-spreading-on-land/ - Time-lapse DEM shows growth of Mount St. Helens lava dome between 2004 and 2008: growth that has pushed the Crater Glacier out of the way.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u4ld6EQqY3w&feature=youtu.be

(via @rschott) - Spectacular footage from White Island NZ: really shows how much more active it is than when I visited 10 years ago.

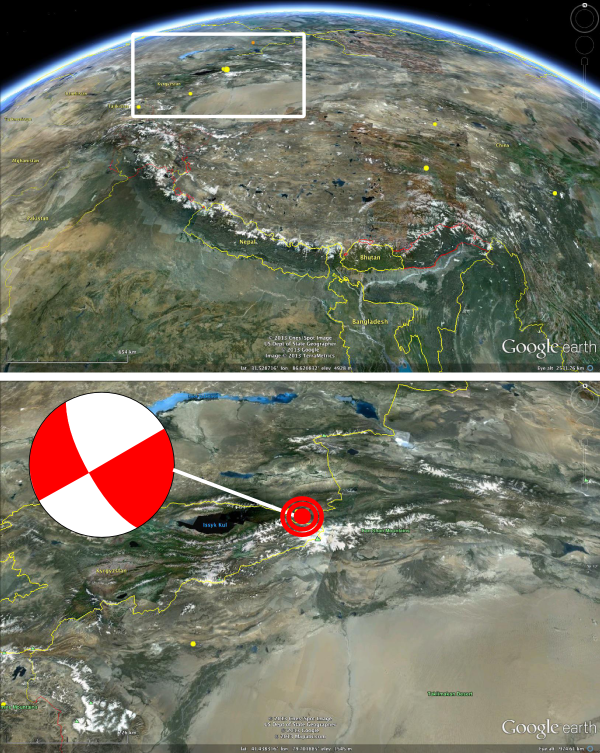

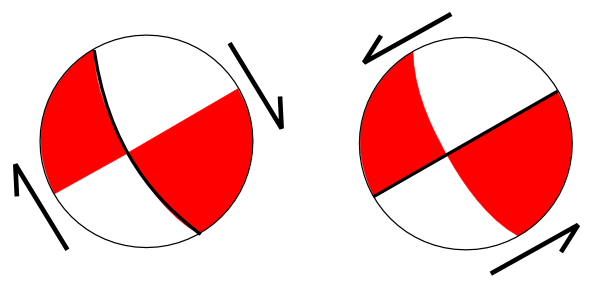

Earthquakes

- Last Saturday marked 313 years since the last great earthquake on the Cascadia subduction zone.

http://www.pnsn.org/blog/2013/01/24/the-last-cascadia-great-earthquake-and-tsunami-313-years-and-ticking

Planets

- A very nice summary of what we’ve learnt from Dawn’s sojourn at Vesta

http://blogs.jpl.nasa.gov/2013/01/the-giant-asteroid-a-retrospective/

(via @ProfAbelMendez) - Eruptive history of Olympus Mons reconstructed using only topography & how crust has deformed under its weight.

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0012821X12007066

(Paleo)climate

- Oldest ice core recovered from Greenland suggests ice sheet there might be more stable than thought?

http://blogs.agu.org/wildwildscience/2013/02/01/greenland-ice-core-may-rewrite-some-climate-books/

Water

- Interesting article on the growth of green storm water management projects in US cities. Key quote: “nature is often very good at things we humans find hard to accomplish through classic, straight-line engineering”.

http://e360.yale.edu/feature/to_tackle_runoff_cities_turn_to_green_initiatives/2613/ - Traditional fossil fuel plants: 10-60 gallons #water per kWhr electricity. W/dry cooling? 0.8. Solar and wind? Zero.

http://www.pacinst.org/reports/water_for_energy/

(via @PeterGleick) - Brisbane central business district to be flooded for 2nd time in 3 years (as it has been flooded many times before)

http://www.perthnow.com.au/news/national/brisbane-cbd-braces-for-its-second-flood-in-two-years/story-fndo6bgc-1226563818419

(via @watersecurity) - Video: Sinkhole near a construction site in China swallows several buildings:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/china/9833738/Sinkhole-swallows-whole-building-complex-in-China.html - Water main break floods part of NYC:

http://gothamist.com/2013/02/01/water_main_break_floods_flatiron_di.php#photo-12

(via @jmunshi_south) - Took my students to the Cuyahoga in Kent last week, site of what I think is a really good dam removal compromise:

http://www.kentohio.org/reports/dam.asp - Sonic daylighting of an urban stream – fascinating idea! Broadcasting sounds of buried river

http://www.jordandalton.com/scajaquada/proposal.html

(via @WoodinRivers, @losturbanrivers) - CSO fix + stream restoration! : Philadelphia #daylighting the Indian Creek – a #losturbanriver

http://planphilly.com/articles/2013/01/21/daylighting-project-reveals-a-hidden-creek

(via @losturbanrivers) - Interesting sounding new paper in Nature Climate Change: Major flood disturbance alters river ecosystem evolution (paywall)

http://www.nature.com/nclimate/journal/v3/n2/full/nclimate1665.html?WT.ec_id=NCLIMATE-201302#/affil-auth

Environmental

- Maggie Romuld (@rivrchik) wrote about what she saw when I sent her a picture through my office window: http://www.maggieromuld.ca/2013/02/01/through-highlyannes-window/

- Nicholas Stern: ‘I got it wrong on climate change: it’s far, far worse’

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2013/jan/27/nicholas-stern-climate-change-davos - What will departing US Energy Secretary Steven Chu’s Legacy Be? As with most pieces asking such questions, answer is ‘come back in 20 years’.

http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/2013/02/01/what-will-steven-chus-energy-legacy-be/ - US energy report suggests natural gas and renewables industries in ‘unholy alliance’ to see off coal.

http://climatedesk.org/2013/01/charts-renewables-in-bed-with-natural-gas/

General Geology

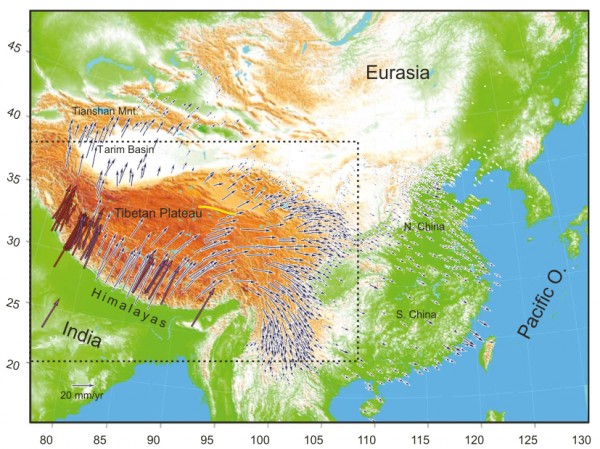

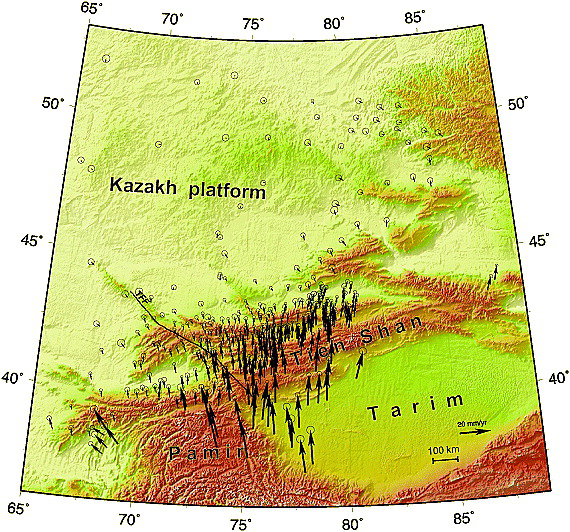

- Matt Hall concedes that calling Euler a geophysicist is a bit rich, but argues we couldn’t do geophysics without him. He also derived Euler poles, which describe the motion of rigid plates on a sphere – so we couldn’t do plate tectonics without him, either.

http://www.agilegeoscience.com/journal/2013/1/29/great-geophysicists-7-leonhard-euler.html

(via @kwinkunks) - Nice post by Garry Hayes on aerial interpretation of geology from drainage patterns.

http://geotripper.blogspot.com/2013/01/the-airliner-chronicles-wrinkles-tell.html - Mantle xenoliths contain primary magnetite that may be able to carry stable remanence at upper mantle temps/pressures.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2012GL054100/abstract

Interesting Miscellaney

- @BoraZ unveils his latest blogging opus, this time on blog comments. We don’t generate vast comment threads here at Highly Allochthonous, but the ones we get are excellent, and we value every one.

http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/a-blog-around-the-clock/2013/01/28/commenting-threads-good-bad-or-not-at-all/ - A good post on the trickier aspects science outreach, although like ‘impact’, seems ‘outreach’ has as many definitions as there are people in the discussion.

http://scienceblogs.com/sciencepunk/2013/01/26/1195/ - Boo! Miriam Goldstein going on blogging hiatus! But yay! It’s because she’s going to be kicking ass and taking names in DC!

http://deepseanews.com/2013/01/to-take-arms-against-a-sea-of-troubles-my-life-in-blogging-and-farewell/ - Past attempt to coin another grandiose-sounding buzzword, some interesting points : Why we need ‘Long Data’, not just ‘Big Data’

http://www.wired.com/opinion/2013/01/forget-big-data-think-long-data/

(via @EuroGeosciences) - Emphasis is on the ‘could’, but always fun to dream big technological dreams: 7 Massive Ideas That Can Change the World

http://www.wired.com/business/2013/01/ff-seven-big-ideas/all/ - Hmm. ‘Near-living’ crystals? Interesting self-organising behaviour, but save the hype for when you nail replication…

http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2013/01/living-crystal/ - A elegant real-time representation of the global tweeting patterns.

http://tweetping.net/ - Worth revisiting: Where are the women geoscientists?

http://www.agiweb.org/workforce/Currents/Currents-033-GenderOccupations.pdf

Nice plan for content warnings on Mastodon and the Fediverse. Now you need a Mastodon/Fediverse button on this blog.