![]()

![]() Our last day in Antarctica was filled with a few of my favorite things, and I wished at our last two stops, as I had at many, that we had lots more time to explore and soak in the scenic and geologic richness of our surroundings.

Our last day in Antarctica was filled with a few of my favorite things, and I wished at our last two stops, as I had at many, that we had lots more time to explore and soak in the scenic and geologic richness of our surroundings.

Even from outside the caldera, Deception Island’s volcanic heritage is evident. Photo by A. Jefferson.

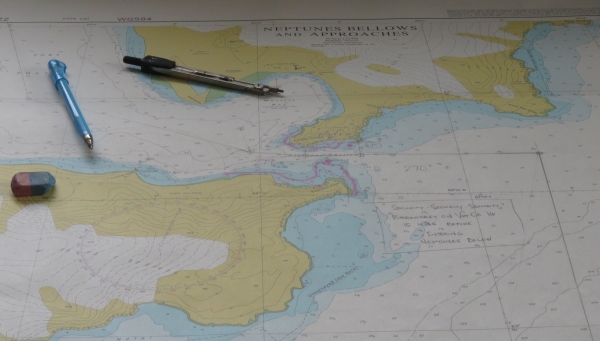

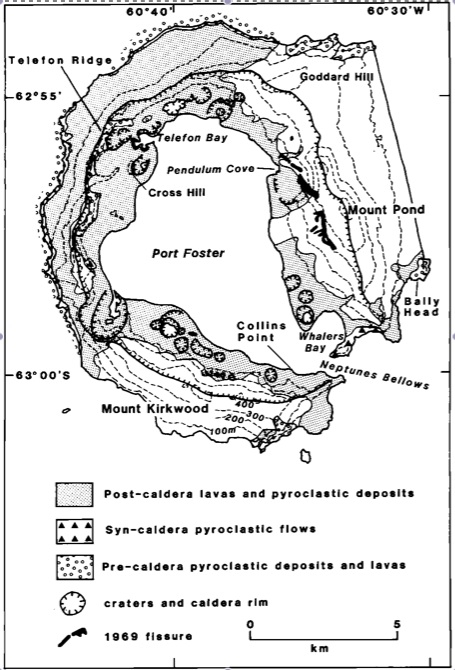

In the morning, we came upon Deception Island, a long-lived shield volcano with a large flooded caldera. There is one narrow and treacherous opening into the caldera, through which ships must carefully navigate to reach the 10 km by 7 km, 190 m deep “Port Foster” on the inside. This opening, called Neptune’s Bellows, allegedly has a submerged rock in the center which has caused significant damage to a number of ships. While our captain was engaged in those maneuvers, we were busy looking at a slice through the volcano.

Deception Island is one of the best studied of Antarctic volcanoes, but like all geologic features in Antarctica, knowledge of it is also limited by ice cover. The caldera forming eruption is thought to have occurred in the last 700,000 years, and pre-caldera rocks are not well-exposed. Where they are found, these old rocks are yellow palagonite tuffs with lava and scoria interbeds. To translate for the non-volcanologists, palagonite tuffs have bits of volcanic glass (with a basaltic composition) embedded in a matrix of palagonite, which is alteration product that results when hot basaltic lava & glass come into contact with water. Basically, it’s a really good indication that there was water around when these deposits were formed. In this setting, that water could be either sea water or snow and ice. The lava and scoria interbeds suggest that at least some eruptions took place in drier conditions. The caldera-forming eruption (think Mt. Mazama becoming Crater Lake) is preserved as pyroclastic flow deposits around Neptune’s Bellows.

Looking from the caldera back at Neptune’s Bellows. On the left are syn-caldera rocks (buff). On the right are post-caldera volcanic products (red and gray). Photo by A. Jefferson.

After the caldera-forming eruption, Deception Island has had lots and lots of volcanic activity and there are numerous tuff cones (steep-sloped volcanic vents indicative of water-magma interactions, called phreatomagmatic eruptions), maars (craters created during phreatomagmatic eruptions), and fissure vents. This volcanic activity is largely controlled by a ring fracture system within the caldera. Some lava flows go down the outer edges of the volcano, but most of the activity has been on the low ground inside the ring fracture. The lavas have diverse compositions – ranging from olivine tholeiites to rhyodacites (low silica to high silica). All told, the volcano is 30 km wide at its base below sea level and is 1200 m high from that base.

We made two stops on Deception Island, both showcasing the recent volcanic activity that has shaped the landscape and impacted the people who took advantage of the island’s safe harbor. Within the caldera, eruptions have been witnessed in 1967, 1969, and 1970, and probable eruptions occurred in 1842 and between 1912 and 1917. This is truly an active volcano.

Our welcoming committee at Telefon Bay consisted of Gentoo and Chinstrap penguins, a Weddell seal (not pictured), and some beautiful red kelp(?). Photo by A. Jefferson.

Our first landing took place at Telefon Bay. The beach was black volcanic sand and there was a dusting of snow on the cinder plains, cones, and craters all around us. The beach area itself is probably an old crater, supplanted by more recent volcanic activity. This part of the island was affected eruptions in both 1967 and 1970, and we hiked up to the rim of a crater possibly formed during one of these eruptions. (I’m working from the same geologic map posted above, plus text, so I’m struggling a bit with exactly which bits of the landscape were created when.)

Looking over a 1967(?) crater. Note the people along the crater rim for scale. Photo by A. Jefferson.

From the crater rim, we hiked in a loop across more young volcanic deposits and had views of a lake and new land formed in the 1967 eruption. The landscape had plenty of juvenile material (lots of scoria), but also a bunch of blocks and older material that looked as if it might have come from a lahar deposit. If it weren’t such a volcanically active place, I would have been worried about humans as geomorphic agents eroding the unconsolidated deposits. However, there are a number of places on Deception Island that are both scientifically interesting and ecologically fragile to warrant protection as Antarctic Specially Protected Areas. Volcanic deposits make great places to study ecological succession on surfaces of known age, and the geothermal features and topography of Deception Island means that it is host to the greatest number of rare and extremely rare plant species in the Antarctic. The lake we looked across to, and the land surrounding it, is encompassed by one of these specially protected areas.

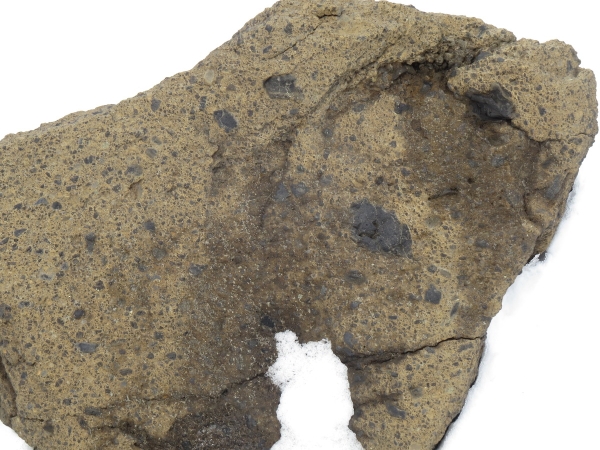

A rock I’m interpreting as an old lahar or pyroclastic flow deposit ejected from a nearby crater quite recently. Photo by A. Jefferson.

Looking towards Neptune’s Bellows from Telefon Bay. I loved the snowdrifts in the lee of the volcanic blocks. Photo by A. Jefferson.

Looking across Telefon Bay towards land created in 1967. This area is now closed to public access as an Antarctic Special Protected Area, because of its ecological fragility and special scientific interest. Photo by A. Jefferson

Crater rim in the background. Hill in front of the crater rim was created as an island in the 1967 eruption and connected to shore by the 1970 eruption. Photo by A. Jefferson.

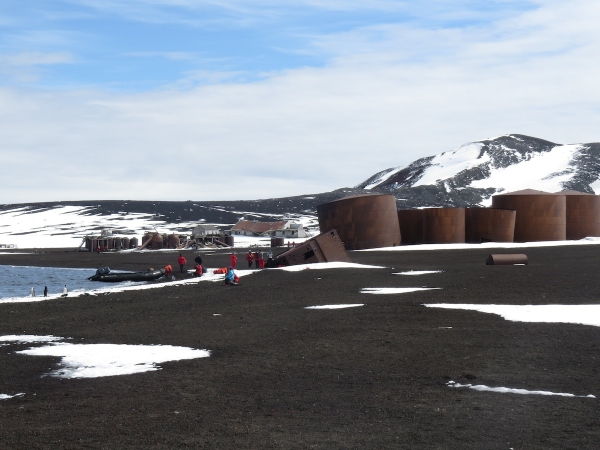

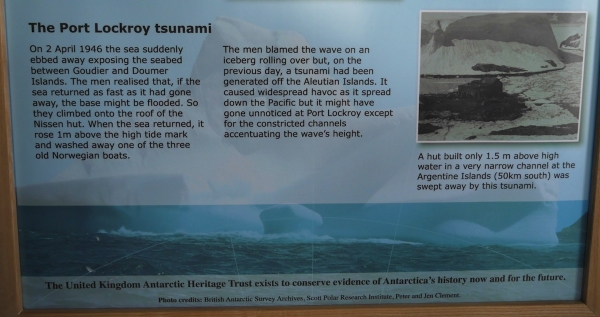

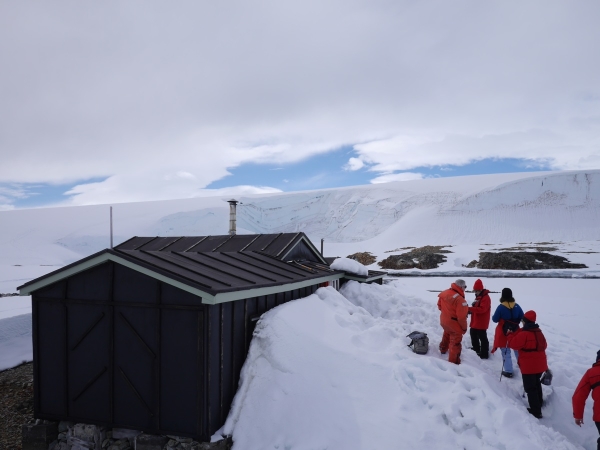

After our explorations at Telefon Bay, we were transported to another site within the caldera, called Whaler’s Bay. This site has the remnants of an old whaling station and a British research station. The whaling station remains (1906-1931) are some of the most significant remains from that awful time of horrific slaughter of tens of thousands of whales each year in Antarctic waters. We’d seen evidence of whaling at Penguin Island and Neko Harbor, but here many of the buildings and fuel oil tanks, whale oil tanks, and cookers were still standing. After the whale processing moved offshore to factory ships, the area was abandoned for a while. In 1944, the British set up a scientific station at Whaler’s Bay and occupied the area until 1969. The Chileans also had a scientific station nearby in Pendulum Cove. Theirs too was abandoned after 1969.

Oil tanks and remains of the whaling station and British station at Whaler’s Bay. Photo by A, Jefferson.

1969 was a year with more volcanic activity in Deception Island’s caldera – in the form of a subglacial fissure eruption that stretched from Pendulum Cove to Whaler’s Bay. As our guides told us, first the Chilean station was hit by pyroclastic ejecta and the Chileans fled for their lives to the British base at Whaler’s Bay. Not long afterwards, the British station was affected by the volcano. The eruption underneath a thin glacier created a meltwater flood and lahar that headed directly toward the British station and caused significant damage to some of the buildings. (Note: if someone has a link that can verify the fleeing Chileans part of this, that would be lovely.) After that, the Chileans and Brits gave up and the only stations on Deception Island now are summer-only ones on the other side of Port Foster. The 1969 lahar also created new land just beyond the British station, now another Antarctic Specially Protected Area, because of its colonization of known age surfaces and the fact it contains the only geothermal heated lagoon in the Antarctic!

The whaler’s graveyard at Whaler’s Bay was partially over-run by the 1969 lahar. Photo by A. Jefferson.

This penguin seemed a bit confused. It spent a long time wandering in circles on the snowbank. Photo by A. Jefferson.

Our final stop of the day – of the trip! – was on Livingston Island, where we got to see the evidence of much older volcanic and biological activity. Livingston Island is huge, complex, and mostly ice covered. But we landed at Walker Bay near Hannah Point, where there was a thin strip of land exposed – ecologically interesting land, both in the modern day and in the Cretaceous. Walker Bay is the eroded remnant of a volcanic caldera formed tens of millions of years ago, when the Antarctic Peninsula was an active volcanic arc above a subduction zone, in contrast to the rift-related modern volcanism at Deception and Penguin Island. The cliffs that back the bay’s beach are a 500 m sequence of basaltic andesite to dacitic lavas, interbedded with pyroclastic and thin sedimentary beds. Two K-Ar dates of the sequence give ages of 87.9+/-2.6 million years and 67.5+/-2.5 million years.

Here, however, it’s the sedimentary beds that are the most geologically interesting, for they contain a rich assemblage of plant fossils. There are 18 taxa recognized from leaf imprints and woody stems, predominantly ferns and conifers of the Podocarpaceae family. Podocarps are classic Antarctic flora, dating from before the breakup of Gondwana and now found throughout the Southern Hemisphere. Interestingly, there is also one angiosperm (flowering plant) identified in the plant fossils at Walker Bay, and angiosperm pollen is also found in the rocks. Because the fossiliferous layers in the middle of the cliff-forming sequence, you can’t walk up things in situ. However, a sort of open-air museum had been created at the back of the beach, with a large number of fossil-rich rocks set up for display. This was a place I particularly worried about the ethos of taking only pictures and leaving only footprints, but our guides at least kept a close eye on everyone. Today, the vegetation at Walker Bay is limited to large patches of moss. Admittedly, this is much more vegetation than at most sites we’d visited, but still quite depauperate compared to what was there in the ice-free late Cretaceous, a good 30 to 50 million years before it entered its current deep freeze.

Anne and her mother Carol Jefferson inspect the Walker Bay Cretaceous plant exhibit. Photo: Chris Rowan, 2013.

The modern plants and animals also cried out for our attention at this site as well. Lots of elephant seals were molting, wallowing, mock fighting, and generally being impressively large and belchy. There were also chinstrap penguins and nesting Southern giant petrels. The visitor code of conduct specifies that humans must stay at least 5 m away from all wildlife, but is also says to stay at least 50 m away from the giant petrels — more if a change in behavior is noted. Don’t mess with a bird with a 2 m wingspan!

Nesting southern giant petrels, observed from a long way away with a very good zoom lens. Photo by A. Jefferson.

Just beyond the beach at Walker Bay is Hannah Point. This area is ecologically rich, with several species of plants and breeding grounds for chinstrap, gentoo, and macaroni penguins, Antarctic (blue-eyed) shags, snowy sheathbills, kelp gulls, Antarctic terns, three species of spetrel, skuas and the aforementioned southern giant petrels. For this reason, the point is closed to visitors during breeding season. I’m glad the area is closed to visitors, and at least my impressive zoom lens gave me a view of what the fertile area looks like.

A long, choppy zodiac ride took us away from Livingston Island and brought an end to our Antarctic landings. Now only a northward crossing of the Drake Passage and series of flights up the length of the Americas were ahead of us.

Smith Island: our last glimpse of the Great Southern Continent as we headed back north. Photo: Chris Rowan, 2013

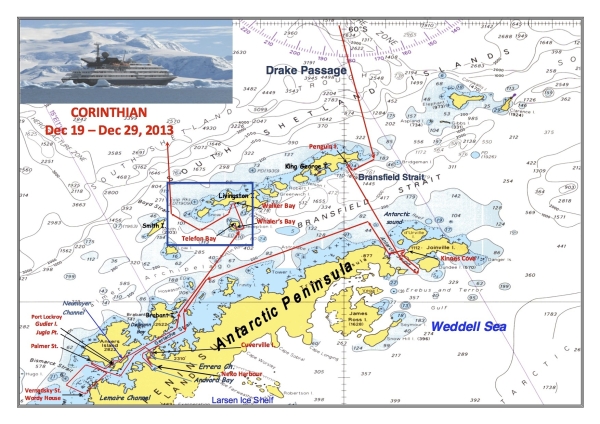

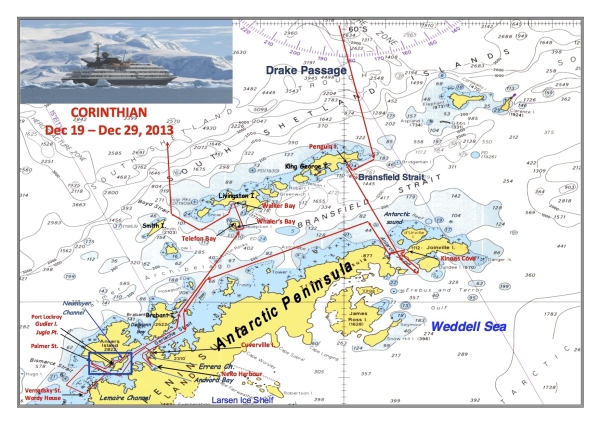

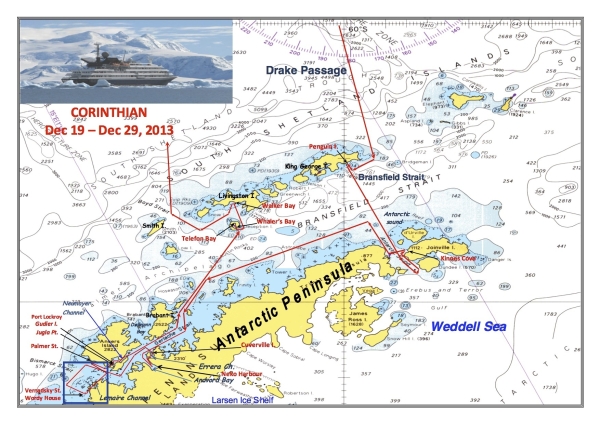

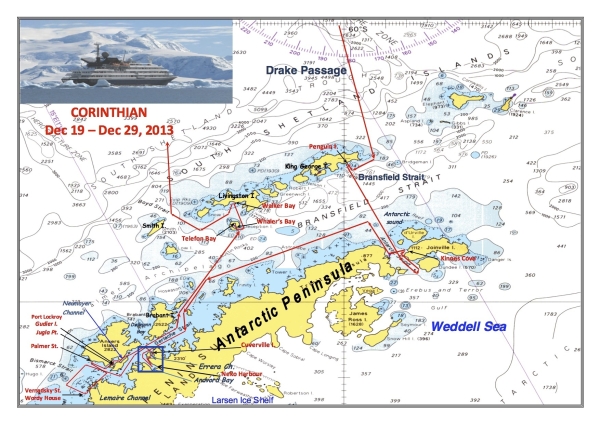

Our areas of exploration on 26 December 2013 are shown inside the blue box at the center of the map.

References:

Smellie, J.L. (1990) D. Graham Land and South Shetland Islands, in Volcanoes of the Antarctic Plate and Southern Oceans (eds W.E. LeMasurier, J.W. Thomson, P.E. Baker, P.R. Kyle, P.D. Rowley, J.L. Smellie and W.J. Verwoerd), American Geophysical Union, Washington, D. C.. doi: 10.1029/AR048p0302

Smellie, J. L. (2002). The 1969 subglacial eruption on Deception Island (Antarctica): events and processes during an eruption beneath a thin glacier and implications for volcanic hazards. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 202(1), 59-79.

Leppe, M., Michea, W., Muñoz, C., Palma-Heldt, S., & Fernandoy, F. (2007). Paleobotany of Livingston Island: The First Report of a Cretaceous Fossil Flora from Hannah Point.

Nice plan for content warnings on Mastodon and the Fediverse. Now you need a Mastodon/Fediverse button on this blog.