(reposted, with some modifications, from ye olde blog)

It seems like megatsunamis are back in vogue, but this time a different culprit is in the frame. Around the turn of the millennium a lot of publicity was given to the suggestion that a 200 cubic kilometre-sized chunk of the western flank of Cumbre Vieja, an active volcano on La Palma in the Canary Islands, was poised to fall into the sea in a future eruption. Modelling suggested such a collapse would send a gigantic tsunami racing westward across the Atlantic, and the eastern seaboard of the US would be assaulted by 50 m high waves that would penetrate up to 20 km inland (for comparison, the Boxing Day 2004 tsunami produced waves 20-30 m high which penetrated 2-3 km inland on the Sumatran coast, a mere 160 km away from the epicentre).

This apocalyptic scenario was put forward by Bill McGuire and his colleagues at the Benfield Hazard Research Centre. McGuire has become the go-to guy when you want a geological scare-quote for your breathless documentary about how we’re all doomed, whether by megatsunami, supervolcano, or some other hyperbolically titled geological phenomenon. In my old department in Southampton, some people who have studied past collapse events in the Canaries think that the risk is being a tad…overhyped (see also here for the Benfield team’s counterargument), because you seem to get a series of much smaller landslides rather than one big one which will Wipe Out the Whole of Western Civilisation.

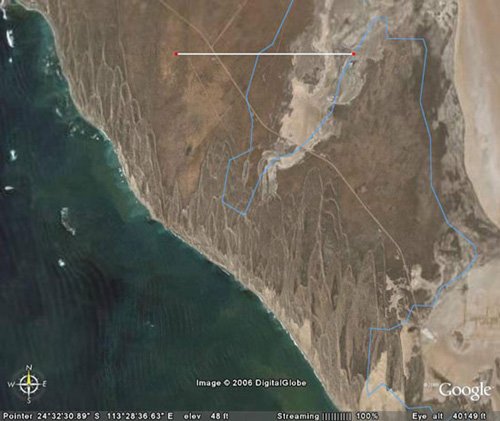

At the end of 2006 Phil called our attention to an article in the New York Times (free registration required) which highlights another potential source for really big waves – oceanic asteroid impacts, which a group of scientists led by Dallas Abbott have proposed as the source of some interesting wedge-shaped deposits, referred to as ‘chevrons’, you find on some shorelines, particularly around the Indian Ocean. Firing up Google Earth, we can find them on the West Australian coast (the line on this and the following images is 5 km long:

Nice plan for content warnings on Mastodon and the Fediverse. Now you need a Mastodon/Fediverse button on this blog.