Whenever you’re trying to talk about science to a broader audience, one of the major challenges is cutting out the jargon. Sometimes, though, the real difficulty is not so much in translating the jargon, as identifying it in the first place. This problem his highlighted by BAllenJ’s comment on my last post:

…when you write these geology posts that the non-geologist can enjoy, could you please use the age instead of the geological name, or even better…along with? I need a secret decoder ring (OK, answers.com) to decode stuff like “During the Cretaceous and early Cenozoic…”

He’s absolutely right, of course. I’ve discussed in previous posts the whys and wherefores of the geological timescale – how it attempts to divide geological history up into distinct chunks, each with its own unique tectonic, climatic and biological character. For geologists, it’s a useful shorthand, because we’re familiar with the geological timescale and know more or less where all of the different periods slot in*. I suspect that talking about named periods rather than absolute age ranges also helps geologists to handle the disconnect between the lengths of time we’re discussing when talking about Earth history (tens, hundreds, and even thousands of millions of years), and the lengths of time that our little primate brains can actually get our heads around (ranging from a handful of years down to seconds, depending on how cynical you’re feeling). Regardless, we’re so used to bandying about ‘Cretaceous’ and ‘Cenozoic’ that we forget that they can be, to the layman, words just as impenetrable as ‘diagenesis’ or ‘turbidite’ (or, indeed, ‘allochthonous‘).

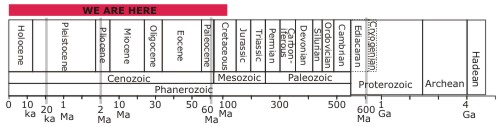

I’m not unaware of this problem, of course, and at a number of places in that post I did provide numerical ages as well as period names. But I didn’t everywhere, partly because I simply forgot to, but also because it’s sometimes difficult to do so without destroying the flow of the text. Also, I’m not entirely convinced that simply inserting the numbers always helps people to really get to grips with where (or when) the hell I’m talking about. Perhaps it would just be easier to show visually when I’m talking about:

This is actually an idea I’ve been toying with for some time, but just hadn’t got around to implementing: place this compressed timescale at the bottom of the post, with the red bar showing the time period I’m talking about, and every time I mention a geological period name, internally link down to it. I’ve just given ‘Tectonics shown to drive changes in biodiversity’ this treatment. Take a look, and let me know whether you think this is a useful addition, or whether I should just stick to adding more numbers. I am a little worried that the text is a little too small, or the logarithmic-esque timescale required to fit everything on nicely might be a little bit confusing. But it’s fun to play…

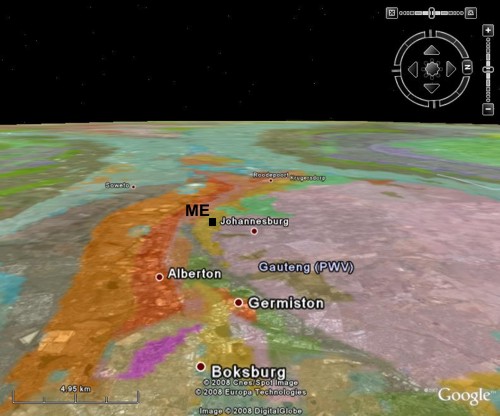

*Of course, even we geologists usually have some shaky areas; as Christie has commented in the past, coming to South Africa gives you a whole new perspective on a period of Earth history which was previously generically filed away under ‘really old stuff’, or ‘that time before multicellular life kicked off’.

Nice plan for content warnings on Mastodon and the Fediverse. Now you need a Mastodon/Fediverse button on this blog.