![]()

![]() Christmas Eve in Antarctica involved our first look at how people live and work in this harsh environment – both today and in the early days of exploration – and possibly the most fabulous scenery yet.

Christmas Eve in Antarctica involved our first look at how people live and work in this harsh environment – both today and in the early days of exploration – and possibly the most fabulous scenery yet.

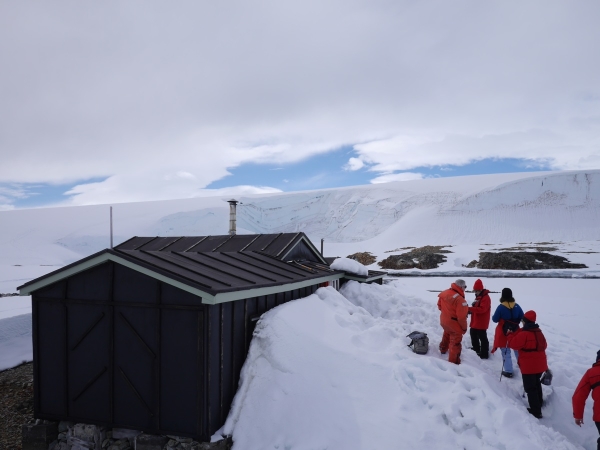

From Anne’s journal entry: “On the night of the 23rd, we made for the USA’s Palmer Station, where we were hoping to be the first tourist ship of the season; unusual ice conditions in the harbour had kept previous visitors away. In the morning I went up on deck and saw a research station that I thought must be Palmer. But it wasn’t – ice had caused us to change course to the Ukrainian Station Vernadsky.”

We later found out that on the other side of Antarctic, another vessel was having considerably more trouble with sea ice than a forced diversion. When we got back home, the first question everyone asked was, ‘was that you?’. It wasn’t – all the ice forced us to endure was a spectacular sunrise in a slightly different location to the one we were expecting. At 65º15′ south, this was also the closest we got to the South Pole on our expedition.

A small (~12 man) outpost located on one of the Argentine Islands, Vernadsky is actually the former British Faraday Station: it was sold to the Ukraine for one pound in 1996. Since the Antarctic Treaty would have required the UK to remove – at great cost – all trace of the base’s existence if it had been shut down, this is not as bad a deal as it might initially seem.

We got a tour of one of the station building, which still bore many signs of its former nationality – lots of signage in English, and the obligatory station pub.

The world’s most southerly pub? A bar installed when Vernadsky was the UK’s Faraday Station. Photo: Chris Rowan, 2013.

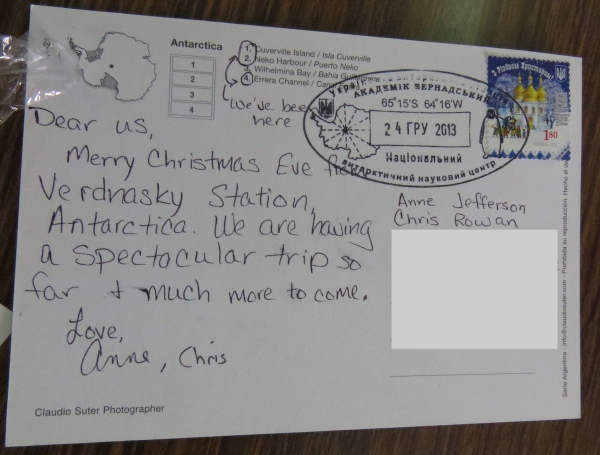

There was also a gift shop that provided to opportunity to send postcards back home via supply ships, a process that could take up to three months. Being scientists, we of course sent one to ourselves so we could time how long it actually took.

Chris also had the opportunity to hike across some (hopefully!) thick sea ice to an earlier iteration of the British Antarctic base. Built in 1947, Wordie House was named after the chief scientist on Ernest Shackleton’s epically abortive 1914-1917 expedition. It operated until 1954, when a new base where Vernadksy now stands was opened. Now a designated historic site, Wordie House gives an insight into what it was like for scientists in the early days of Antarctic research – namely lonely and cramped.

Wordie House: actually the second outpost built by the British on the Argentine Islands: the first was possibly destroyed by a tsunami (!) during the winter of 1946/7. Photo: Chris Rowan, 2013.

Sample supplies for British Antarctic scientists in the 1940s and 50s, on display in Wordie House. At least they had coffee… Photo: Chris Rowan, 2013

But this long occupancy has reaped a rich scientific harvest: meteorological data has been continuously collected here since 1946, giving us one of the longest climatic records from the Antarctic. (continuing these measurements was one of the conditions of the British handing over Vernadsky). Longer-term records like this help us to understand the current rapid warming in this part of the world a little better. Monitoring at this station was also pivotal in our discovery of the Antarctic ozone hole.

On his return inter-island treck, Chris noted some crevasses opening up at the contact between the sea ice and the shore. This was definitely the right time to notice these.

The weather remained fine – fine enough that lunch was served outside on one of the upper decks. As excellent as the food was, the real star was the scenery, which managed to become even more spectacular as we cruised northeast up the Lemaire Channel. You may have trouble believing these photos – we do, and we were there! – but it really was that scenic.

Anne: “we sailed through a narrow channel with high cliffs, glaciers and icebergs on either side of us. Chris and I (and many other passengers) stood on deck the whole time – taking lots of pictures and enjoying the good weather and scenery. A highlight for me was happening to see our ship strike a glancing blow on a bergy bit and watch it break in half”.

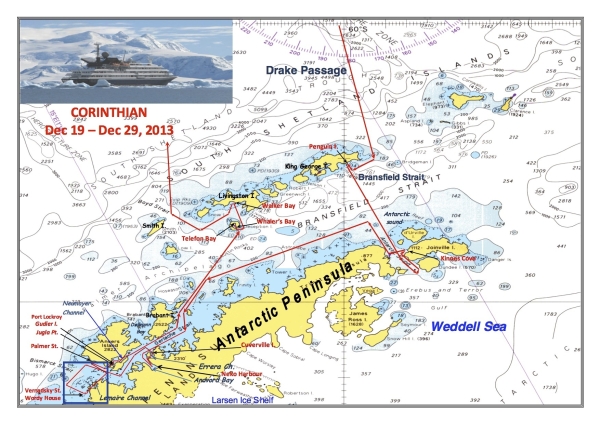

Where we were today:

Nice plan for content warnings on Mastodon and the Fediverse. Now you need a Mastodon/Fediverse button on this blog.