Early this morning a magnitude 6.3 earthquake struck Italy, centred on the city of L’Aquila to the north-east of Rome. The BBC reports that at least 150 people have been killed, and tens of thousands may have been made homeless.

Earthquakes in this region are not unusual: this map of seismicity between 1981 and 2002 from the INGV shows, Italy experiences frequent shallow earthquakes, mainly distributed along the Apennine mountain range that runs along the northeast coast (sorry for the squint-inducing nature of this – you could also have a look at this rather crowded USGS version). Typically these earthquakes are smaller, a high magnitude 5 at most, but nine of magnitude 6 or greater have occurred in the last hundred years or so.

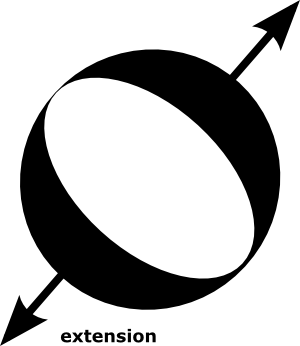

All this activity is the result of Italy being right in the thick of the slow collision between the African and Eurasian plates that has, amongst other things, resulted in the uplift of the Alps. At first glance, it is therefore quite surprising to see that the focal mechanism for this earthquake is characteristic of an extensional earthquake, due to stretching of the earth’s crust, not a compressional one. The extension is oriented in a northeast-southwest direction, at right angles to the Apennine range:

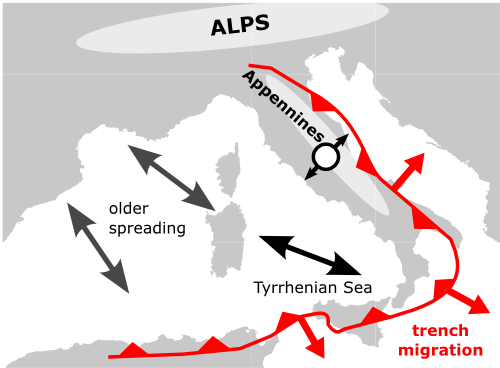

So why is extension occurring in a mountain range? The tectonic history of the western Mediterranean is actually quite complicated; rather than being the last remnants of a large ocean that has been mostly destroyed by subduction as Africa and Europe move together, the oceanic crust here has actually all been created by back-arc spreading in the last 40 million years or so, as the collision zone (marked by the red line which runs around the east and south-east coast of Italy and Sicily and into North Africa), has migrated south and east away from Europe, stretching out the crust in the over-riding plate as it does so.

So although at a broad regional scale two plates are colliding, at a more local level the current back-arc spreading in the Tyrrhenian Sea to the southwest appears to be a major driver of tectonics in Italy, to the extent that thrust faults that built up the Apennines are now being reactivated as extensional normal faults. Unfortunately, this switch doesn’t make the earthquakes themselves any less damaging when they do occur.

Comments (15)