![]() The Highly Allochthonous family got pretty lucky on our trip to Antarctica: we enjoyed calm seas, including both ways across the infamously stomach-churning Drake Passage, and fairly clement weather every day of our trip.

The Highly Allochthonous family got pretty lucky on our trip to Antarctica: we enjoyed calm seas, including both ways across the infamously stomach-churning Drake Passage, and fairly clement weather every day of our trip.

Our Antarctic vessel, surrounded but not hemmed in by sea-ice, Neko Harbour. Photo: Chris Rowan, Dec 2013.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the continent, the MV Akademik Shokalskiy, on a cruise designed to follow in the footsteps of early 20th century explorer Douglas Mawson, found itself trapped in thick sea-ice by unfavourable winds.

The Akademik Shokalskiy has got a bit more up close and personal with the ice. Source: BBC

Fortunately, neither the ship nor its crew and passengers were in real peril, and the passengers have now been rescued. But their misadventures have not gone without criticism, most prominently highlighted by Andy Revkin at the New York Times. These criticisms basically boil down to two main points of contention:

- the rescue efforts, which have diverted icebreakers from several nations from their scheduled duties, have heavily disrupted other Antarctic research: Revkin highlights how the speedy dispatch of the Australian icebreaker from their station in East Antarctica has delayed the offloading of supplies and research equipment.

- the spectacle of climate scientists getting trapped in ice on an Antarctic research cruise has “energized climate change contrarians”, who have been loudly chortling about it online.

The first accusation can’t be dismissed out of hand, although the language in which it is expressed – describing it as an ‘unessential’ ‘bungled’ ‘misadventure’ that has badly disrupted ‘serious science’ (all words used in Revkin’s piece, and mirrored by his continued highlighting of criticism on his Twitter account, where ‘fiasco’ is a commonly used adjective) seems rather judgemental. You can’t question the disruption, but some of that appears to be just the nature of working in Antarctica. It’s a big, harsh, environment with long supply lines and only a limited pool of local resources, which means that any unscheduled events, such as your icebreaker getting stuck in ice itself, or your government taking a while to decide if it wants to fund itself or not, can have serious and long-lasting knock-on effects on everyone working down there. In an already disrupted season, seeing your supply ship sail off to rescue someone else is no doubt an additional frustration. But while it is pertinent to question whether, by trying to stick to a fixed itinerary rather than adapting to the prevailing conditions, the expedition took unnecessary risks, a strong apparent undercurrent of much of the criticism is that the cruise was not ‘real science’ and should never have been dispatched to Antarctica in the first place. Expedition leader Chris Turney has written a strong defence of its scientific merit, but personally, the implicit comparison to cruises like ours, which didn’t pretend to be anything more than tourism*, seems unfair.

As for the assertion that this has provided succour to the climate denial industry, colour me unconvinced. Long-term observation of the corner of the internet occupied by the self-proclaimed ‘sceptics’ indicates that you hardly need to throw them bones; they’ll seize onto any happening, anywhere, that they can trumpet as part of their narrative (regardless of the actual facts of the matter). In fact, from where I’m sitting in Ohio, it’s easy to predict what their fixation will be this week:

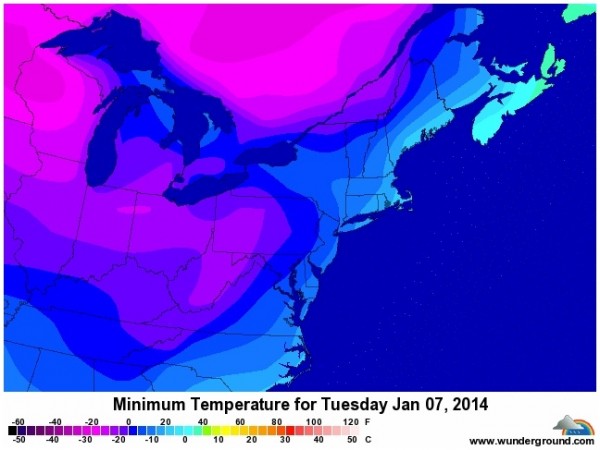

It’s a bit chilly in these here parts right now. Forecast map from Weather Underground.

Yes, the old ‘cold spell, therefore no climate change’ canard. Of course, there’s also a record heatwave in Argentina right now (something I personally experienced whilst dashing around Buenos Aires airport, on our somewhat less-than-smooth return journey to the northern hemisphere), and Australia has just had the warmest year on record, but we all know that warm-weather anecdata don’t count, right? Sadly, whilst managing to grasp that no one individual event can be definitively be used as evidence of anthropogenic climate change, there is a mysterious failure on the part of some to realise that the converse is also true.

*Antarctic cruise operators take seriously minimising damage to the unique and fragile environment we were privileged to see close-up, and we are hoping to share some of our experiences in future posts; but the only data we brought back was in our digital cameras.

Comments (3)