![]() One of the big challenges of my new job is managing my teaching load, which requires me to prepare and then give four 75 minute lectures a week, every week of term. The challenge is especially great in this, my first semester on the job, since both of the courses I’m teaching are new to me. Although there is some overlap with courses I’ve taught before in Southampton and Edinburgh, much of the time I’m starting from scratch.

One of the big challenges of my new job is managing my teaching load, which requires me to prepare and then give four 75 minute lectures a week, every week of term. The challenge is especially great in this, my first semester on the job, since both of the courses I’m teaching are new to me. Although there is some overlap with courses I’ve taught before in Southampton and Edinburgh, much of the time I’m starting from scratch.

Lecture preparation is therefore a big part of my workload at the moment. A rule of thumb I’ve seen bandied about suggests about two hours of preparation for every hour of lecturing. That may be about right, although I’m finding it depends greatly on the course content. For subjects I have previously taught, I already have some idea of how I want to present it and can move right into writing the lecture; but for subjects that I haven’t really taught before, there’s the additional step of making sure that I understand the material, and have clarified the major points that I need to cover, before I can get to actually preparing slides and figures.

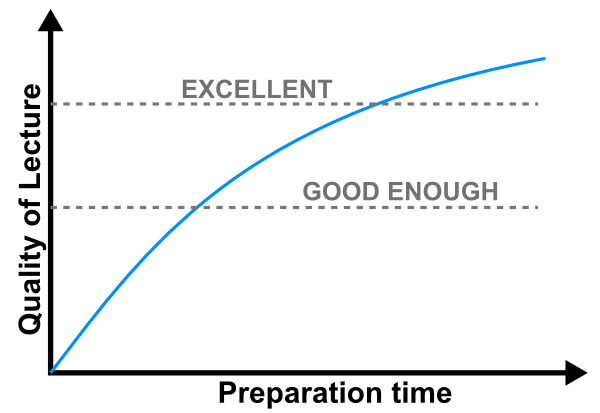

One thing I have noticed, however, is that regardless of when I actually start my preparations, I still find myself tweaking them the hour before I’m due to give them. It seems that like so many other things, lecture preparation expands to take up the time available. More significantly, the return on my time investment does not stay constant: working twice as long on a lecture does not mean it is twice as good. Whilst there is clearly some lower bound below which you don’t have a viable lecture, past a certain point you move from mostly creation – amassing material, creating slides and coming up with worked examples – to mostly tweaking – changing slide order, refining text and figures, creating more detailed notes. This time is not wasted – the lecture will still get better – but the amount of benefit gained for a given chunk of time starts to level off.

The asymptotic lecture preparation curve: as your improve your course materials, it takes more and more time to improve them further.

This is why I can find myself working on my lectures on the day I give them even if I started my preparations in plenty of time: because you’re not ever going to honestly say that you have created the perfect lecture on, say, earthquake seismology, you can always find ways to improve it. But this is also where things get dangerous for this humble junior academic: if I want my research career to continue, then I need to be writing and publishing papers, planning and starting future investigations, and writing and submitting grant proposals. And it is becoming clear that I am need to actively, deliberately, make the time in my schedule to do these things. If I still need to work on tomorrow’s lectures, I need to put that aside and still spend this morning writing that paper, doing that reading, or writing that code: otherwise I could quite easily spend the entire day getting those animated slides just right.

The trade-off here is that obviously, if I’m limiting the time I’m spending on my lectures, they’re not going to be quite as good as they could be if I did eschew a morning of paper writing to work on them as well. This is not something I’m particularly comfortable with yet, but it’s part of the balancing act I need to perfect: spending enough time overseeing all my areas of responsiblity without neglecting something or running out of hours in the day.

My only comfort is that no lecture plan survives contact with the audience: things that work well in your head, or on your own in your office, don’t work quite so well in the lecture hall. So my aim at the moment is to commit enough time to produce good lectures, that clearly set out the key concepts my students need to learn; but to leave the more involved tweaking until next time I teach these courses, when I have a better idea of which tweaks will be most effective, and where I need to spend time making my lectures clearer or more evocative. And because I’ll not be starting from nothing, on the next iteration the hours I allocate can be used to move higher up the asymptotic curve.

The other thing I’ve discovered in the past few weeks – and I probably shouldn’t find it so surprising – is that seven years of blogging about earthquakes, tectonics and other geological matters is an invaluable source of interesting case studies and explanatory figures that quite nicely illustrate important concepts. In that respect, in between stressing about time management, I’m actually quite enjoying reaping what I’ve sown.

Comments (6)