![]() Imagine that one day, an apartment block in a major city catches fire. The fire brigade arrive too late, and the whole block burns down with people still trapped inside. An investigation reveals that the building’s fire alarm system was faulty and did not send out any warning to the residents, or the fire service. The survivors of this disaster seek legal redress against the owners of the building for failing to protect them. ‘The alarms should have sounded and warned us,’ they say. Would you agree with them? Most people probably would.

Imagine that one day, an apartment block in a major city catches fire. The fire brigade arrive too late, and the whole block burns down with people still trapped inside. An investigation reveals that the building’s fire alarm system was faulty and did not send out any warning to the residents, or the fire service. The survivors of this disaster seek legal redress against the owners of the building for failing to protect them. ‘The alarms should have sounded and warned us,’ they say. Would you agree with them? Most people probably would.

Now imagine that instead of burning down, the apartment block is burgled, and a resident who walks in on the thieves ends up being shot. Just before this, a spate of armed robberies in the local area got some press attention, and in an interview the chief of police says something along the lines of ‘we’re investigating, but crime rates are not significantly higher than usual, so please stay calm.’ An investigation in this case shows that security in the building was somewhat lacking: doors were often left unlocked. The residents again seek legal redress – against the chief of police. ‘You shouldn’t have played down the obvious danger to our building,’ they say, ‘if only you’d said we were going to be burgled, we would have made sure the doors were locked.’ Would you agree with them now?

In the L’Aquila earthquake trial, which has just concluded with the conviction of six scientists and one official for multiple counts of manslaughter, the prosecution made (and the court apparently accepted) an argument akin to the first scenario: the scientists failed to sound a proper warning (or, as the prosecution put it, they provided ‘false reassurance’ by saying there was no increased risk) before the magnitude 6.3 earthquake struck in April 2009, and they are therefore culpable for the 309 deaths that resulted. However people try to spin it into being about poor risk communication rather than a failure to predict the unpredictable, the basic underlying argument remains that there should have been a warning, but there was not, and therefore people died.

However, as I argued back when the trial first kicked off, there was no scientifically justifiable reason to think there was an elevated risk of a large earthquake, beyond the background risk of living in a seismically active region with a history of large earthquakes. The regional swarm of smaller earthquakes that prompted the fateful meeting between the scientists and the Italian Civil Protection Agency said nothing about the chances of an earthquake within the next week, within the next month, or the next 5 years – except in hindsight.

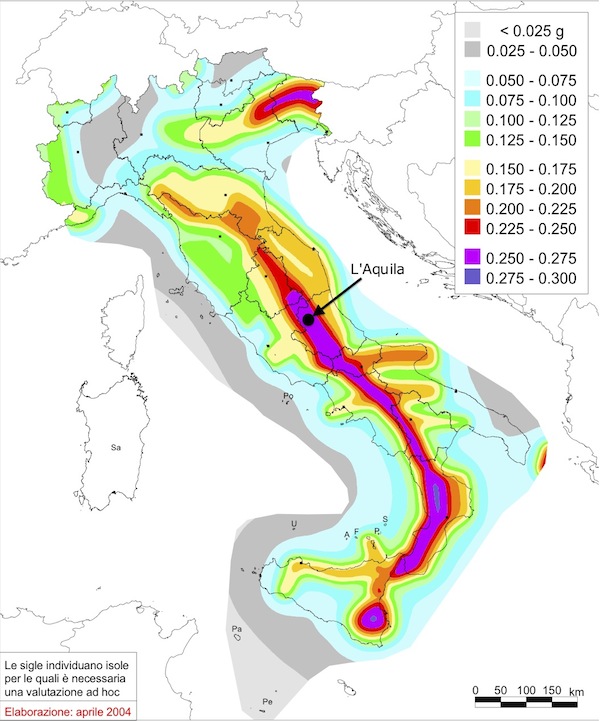

Seismic hazard map for Italy, showing the peak ground accelerations that have a 10% chance of being exceeded in 50 years. There is always a high earthquake risk near L’Aquila. Source: INGV.

In fact, I’d argue that this situation was a lot more like the second scenario I described above; that earthquake hazard is much more akin to crime rates than fire risk. Crime is a fact of life in a big city, and if you’re sensible you don’t wait for specific warnings to take precautions. Every day, regardless of any specific crime wave going on at the time, you lock your doors; you secure your valuables; you take care where you walk at night. These everyday, habitual actions minimise the risk, but everyone is aware that despite these precautions, you might still get burgled. The police chief’s comments were not intended to imply there was no risk of crime at all, and in an ideal world should probably have ended with an admonition to take the normal precautions of locking your doors. However, if the residents of the burgled flats were unaware that cities have higher crime rates, and certain actions make you safer, and suffered as a result of this lack of knowledge, I’m not sure you can assign blame to one man speaking in one interview: it points to a much deeper communication issue.

In a similar fashion, there is never a time when the people of L’Aquila are not at risk of a large earthquake – it’s a fact of where they live, irrespective of what background seismic activity is occurring at any particular time. The downfall of the prosecuted scientists appears to be that they made their assessment of no elevated risk in this context, not realising that most people (including, perhaps, Bernardo De Bernardinis, the convicted Civil Protection Agency official) did not understand that “no elevated risk” did not mean “no risk”. This points to a communication failure, but a long-lived, systemic one, not specific to these scientists and one press conference.

In earthquakes, lives are almost never saved by evacuations before the fact, because specific, timely warnings are currently scientifically impossible. They are saved by rigorous and well-enforced building codes, and a populace that knows to drop, cover and hold on. This is why the L’Aquila verdict is so damaging: not only will it have a chilling effect on what scientists are willing to say in public about the geological risks an area or population face, but it reinforces the all-too-common idea that earthquake safety is like a fire alarm; you only need to take action when there is a specific short-term warning. It’s like expecting the police to show up at your door to warn you that your house is probably going to be robbed tomorrow – and only then locking your doors. We need to get people focussed on the door locks – basic, everyday actions that improve their safety – instead.

Comments (13)

Links (6)-

-

-

-

-

-

Pingback: L’Aquila Earthquake: Trial, Verdict and Response | Adventures in Geology

Pingback: Conviction of Italian seismologists – a nuanced warning « The Trembling Earth

Pingback: What’s up? The Friday links (46) | paleoseismicity.org

Pingback: mastering astronomy | I’ve got your missing links right here (27 October 2012) | Not Exactly Rocket Science

Pingback: Stuff we linked to on Twitter last week | Highly Allochthonous

Pingback: Seismologists Convicted in Earthquake Case - Forbes