![]() It’s pretty hot here in Chicago right now, and the forecast says we’re going to spend most of the next week sweltering. It’s apparently shaping up to be the hottest June in a quarter of a century.

It’s pretty hot here in Chicago right now, and the forecast says we’re going to spend most of the next week sweltering. It’s apparently shaping up to be the hottest June in a quarter of a century.

Forecast for Chicago on Weather Underground this morning. for the not metric people, 38 C is about 100 F.

In the face of these temperatures, I have to admit that I’m glad I can retreat to my cool, air conditioned office for some relief. It is a rather guilty relief, though, since I’m aware that a lot of energy goes into cooling my department so far below the outside temperature. Of course, I come from a country where air conditioning is relatively rare, especially in a domestic setting. A quick look at the current weather conditions in my homeland should give you a clue as to why; the UK has a summer barely worthy of the name more often than not, and even in a “good” one you might only feel the need for some artificial cooling a handful of weeks in a year, which hardly make the economics of buying and installing an air conditioner compelling. It is a definite luxury. The US is a different story: there are swathes of the south and central US where it would be difficult to function if you were left totally at the mercy of the ambient summer temperatures; US cities like Las Vegas and Orlando were built with the assumption that houses would be air conditioned as surely as they were built on the assumption that every family would own a car – for better or for worse, in both cases.

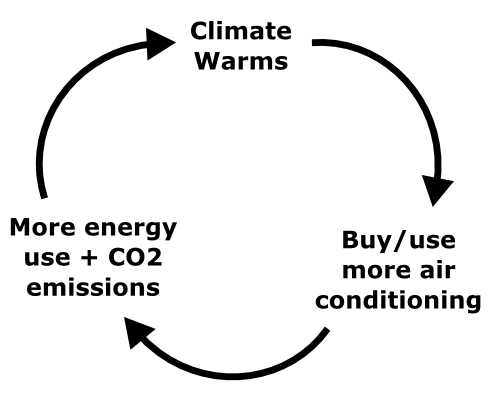

So I can acknowledge that air conditioning is more useful and important in the US, even if I still balk at the notion that it’s some sort of right (the Twitter hashtag #firstworldproblems would appear to be appropriate for that one). But the issue of the environmental cost of keeping ourselves comfortable still troubles me; and in a summer that seems to be delighting in breaking temperature records left, right and centre, I found myself contemplating the paradox that through our increasing greenhouse gas emissions, we might be increasing our demand for air conditioning – and part of those greenhouse gas emissions are the result of the operation of air conditioners. Could this be an example of a positive feedback loop?

Positive feedback loops are often talked about in relation to global warming. There’s the ice-albedo feedback, whereby melting ice exposes land (or in the Arctic, sea) that absorbs rather than reflects solar radiation and drives more melting. There’s also the worrying notion that warming in the polar regions will destabilise gas hydrates and release large amounts of methane into the atmosphere, which will further accelerate warming. But these feedbacks are all entirely due to natural systems responding to our perturbation of the atmosphere, whereas this would be a positive feedback to global warming within our own civilisation: the increasing temperatures could be altering our behaviour in a way that will further warm the climate. It’s an interesting notion; the big question in my mind is the parallel effect of increased winter temperatures reducing the amount of energy we use for heating, which could entirely cancel out the increased summer energy use.

I’m also wondering if there might be other potential examples of civilisational feedback loops. One other possibility I’ve been considering is the relationship between agriculture, population growth, and soil degradation: more agriculture (and soil usage) supports faster population growth, that demands more agriculture. But that is complicated by the notion of carrying capacity – there is only a finite amount of land you can farm, and this would put a brake on a runaway feedback effect. Any other suggestions? Some possible negative civilisation-driven feedbacks would also be nice, if only to make us feel a bit better about ourselves.

Comments (2)