![]() This view up the south-western slopes of Kohala volcano on the Big Island of Hawaii is a study in climatic contrasts.

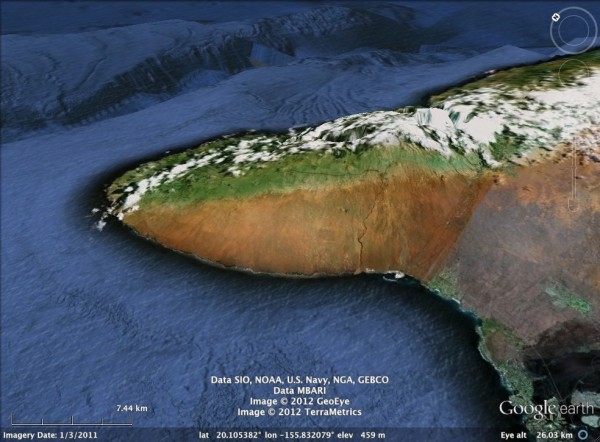

This view up the south-western slopes of Kohala volcano on the Big Island of Hawaii is a study in climatic contrasts.

Looking north-east towards the summit of Kohala volcano, Big Island, Hawaii. Photo: Chris Rowan, 2012.

The ground that I’m standing on is dry, and clearly arid: the sparse and obviously parched vegetation suggests that this landscape sees very little rainfall most of the time. Yet at the very moment I took this photo, the top of Kohala itself is wreathed in storm clouds. When we visited the summit earlier in the day, the weather was fortunately a little more amenable, but the green, green grass and the forests on the summits of the cinder cones show that it is no stranger to precipitation.

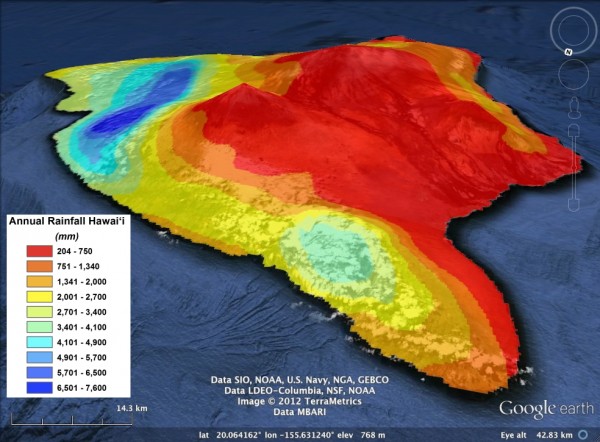

From altitude, the contrast between the lower and upper slopes is even more striking.

This is all caused by Hawaii’s position in the midst of the northern hemisphere’s trade winds, which blow moist air against the north-east slopes of all the Hawaiian islands.

Forced upwards on the other side of Kohala, the air cools, condenses into clouds and rains out all of its moisture as it crosses the summit, created a dry rain shadow on the south-west slope. This orographic precipitation, or “relief rain”, is hardly unique to Hawaii, but the combination of a very tall volcanic mountain, isolated in the middle of an ocean, and fairly constant wind patterns do mean that on the Big Island and other ocean islands experience very large changes in rainfall over exceedingly short distances. From where I was standing, it was less than 10 miles to the other side of Kohala as the crow flies, but along that line the average annual rainfall increases 20-fold (up to 4 metres, compared to 20 cm or less).

Mean annual rainfall for the Big Island. Perspective view from the north: Kohala is the promontory in the right foreground. Google Earth overlay from the Rainfall Atlas of Hawaii (http://rainfall.geography.hawaii.edu/)

The people who guided our trip around Kohala are interested in how these large variations in rainfall affect the development of the volcanic landscape. One obvious effect is on the rate of soil development. The lava in this roadcut is probably around 100,000 years old, and whilst weathering in the dry conditions here has produced some top-soil, it’s fairly thin – perhaps a metre or so. Up near the summit, more rainfall has led to a lot more soil.

Thick soil horizon revealed by a slump on the summit of Kohala, Big Island, Hawaii. Photo: Chris Rowan, 2012.

It’s easy to see why you can get some pretty cool science done in a place with high climatic variability and an easily datable landscape. It’s relatively straightforward to trace a lava flow across many different climatic zones, and since you know that the composition of the initial bedrock and the elapsed time are the same, any changes you observe in processes like soil development will be almost entirely be due to differences in rainfall. It’s rarely so easy to untangle all of these variables. I guess this is why our trip guides endure the extreme hardship of a field season on Hawaii: it gives them the rare opportunity to do fieldwork with good experimental controls. Yes, that must be the reason…

Comments (6)

Links (1)

-

Pingback: Pequenas anotações de viagens virtuais 64 - Uma Malla Pelo Mundo