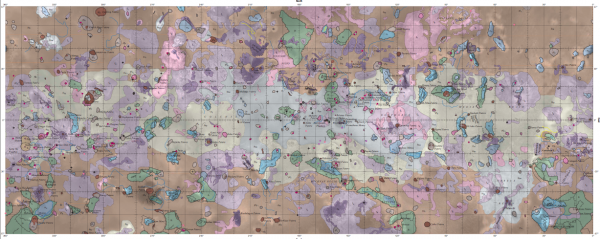

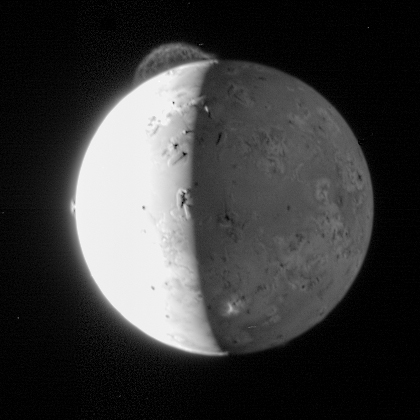

![]() The USGS, in collaboration with NASA, have just released a geological map of Jupiter’s ultra-volcanically active moon Io, based on images from the Voyager and Galileo probes. It is a thing of beauty.

The USGS, in collaboration with NASA, have just released a geological map of Jupiter’s ultra-volcanically active moon Io, based on images from the Voyager and Galileo probes. It is a thing of beauty.

The sheer variety of different geological units that Io’s surface has been divided into is a little eye-opening, especially when you consider that the entire surface of the moon is constantly being resurfaced by the most active volcanoes in the solar system. How can there be so much variety when the whole surface is relatively young volcanic lava?

In fact, the answer is simple: there is so much variety because Io is so geologically active. Hundreds of volanoes are regularly producing individual lava flows, which cover and cut through older flows from the same vent, and other flows from neighbouring vents. Big eruptions dust the surrounding plains with ash. Crater walls collapse and produce debris flows. The surface is faulted and deformed as volcanic edifices are built on top of the crust and magma is extracted from beneath it.

Geological map of Io, zoomed in to part of Io's northern hemisphere. Different lava flows (f_), vents or patera (p_) and crustal blocks uplifted by tectonics (m_) have been distinguished and mapped as separate units. Source: USGS.

So, whilst two bits of rock on Io’s surface might be fairly similar in terms of their composition and mineralogy, they can be very different in terms of their history – how they have got where they are. For geologists, the concept of a ‘mappable unit’ basically boils down to ‘if you can reliably distinguish it, you can map it’, and rocks can just as easily be distinguished by the processes that deposited them, and the relative timing of those processes, as chemistry and mineral content. In the case of Io, for example, lava flows of different ages can be distinguished from each other based on their albedo, colour, and the way they cut across older units, and are themselves cut across in turn. They are thus mappable units, and can be assigned their own colours on a map.

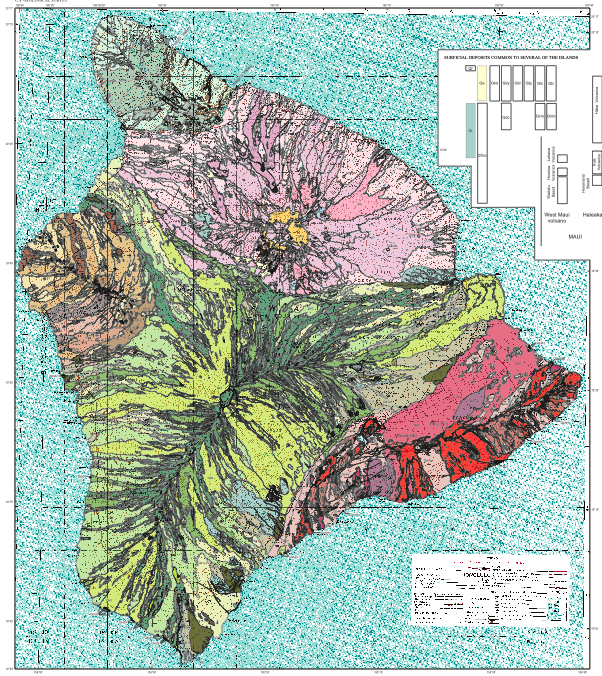

Back on planet Earth, we can see similar principles at work on geological maps of volcanic islands like Hawaii. The whole of the Big Island is effectively made up of variations on a theme of basalt, but assigning it all into one unit would give you a boring – and uninformative – island-shaped blob of a single colour. But different lava flows can be individually mapped, and dated, and traced to different vents, allowing you to produce something a lot more interesting: a map that clearly depicts the rich volcanic history of the Big Island.

Geological map of the Big Island, Hawaii. Not simply all basalt, but all sorts of different basalt. Source: USGS.

It’s not just volcanic rocks either. A single sandstone formation can be mapped as one unit, or divided into individual units representing the different pulses of sediment that have filled up a basin. Glacial tills formed in the last million years can be lumped together, or divided up into markers of the waxing and waning of the ice sheets.

In geology, the composition of a rock and the process that formed it are often intertwined; but even when the type of rock you’re looking at stays the same, the processes forming it can change and give you something entirely new, and distinct – and mappable.

Comments (5)