![]() In Minnesota, two Saturdays ago, the weather was ridiculously warm, but the trees knew it was autumn and were well into their fall foliage fireworks. It was the perfect afternoon to enjoy a walk around one of Minnesota’s most famous natural features. The name of the state derives from the Dakota word minisota for “water that reflects the sky.” Minnesota is also known as “the land of 10,000 lakes,” though the state’s Department of Natural Resources gives the tally as 11,842 lakes greater than 10 acres (4.04 ha) in size.

In Minnesota, two Saturdays ago, the weather was ridiculously warm, but the trees knew it was autumn and were well into their fall foliage fireworks. It was the perfect afternoon to enjoy a walk around one of Minnesota’s most famous natural features. The name of the state derives from the Dakota word minisota for “water that reflects the sky.” Minnesota is also known as “the land of 10,000 lakes,” though the state’s Department of Natural Resources gives the tally as 11,842 lakes greater than 10 acres (4.04 ha) in size.

The lake whose circumference I chose to ramble was Staring Lake in Eden Prairie, a southwestern suburb of Minneapolis. I lived near the lake when I was doing my M.S. degree at the University of Minnesota, but it had been nearly 10 years since last I had walked around the 155 acre (62.7 ha) lake. The trail was as pretty as I remembered, and soon I encountered the spot where Purgatory Creek flows into the lake, draining 42 square kilometers of suburban and urban landscapes.

Staring Lake is a flow-through lake, and a little farther along the trail, Purgatory Creek exits the lake, heading for the Minnesota River. The day I walked the trail, the lake was low, and the streambed for lower Purgatory Creek was mostly dry, with just stagnant pools of water accentuating its meandering channel pattern. I’ve seen both sides of Purgatory Creek flowing much more vigorously, as a Minnesota winter’s worth of snow rapidly melted off the land.

A bluff rises 26 m high, from the south shore of the lake, though the lake itself has a maximum depth of 5 m, and an average depth of 2 m. The lake’s location and topography are the result of Minnesota’s glacial and post-glacial history.

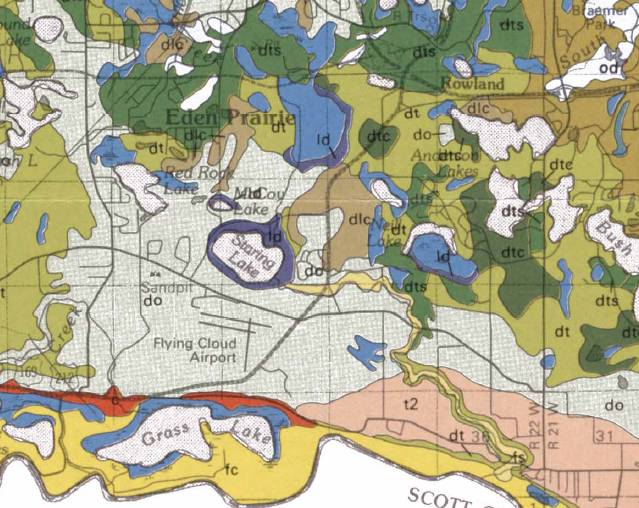

Surficial geology of Staring Lake and surrounding areas, excerpted from Plate 3 of the Hennepin County Geologic Atlas, 1989. The Minnesota river forms the southern boundary of the map area. The gray (do) south of the lake is outwash, the greens are till (dt = loamy till, dtc = clayey till, dts = sandy till), purple is lacustrine deposits (ld), blue is organic deposits (do) (i.e., wetlands), t2 is a Minnesota River terrace, c is colluvium and small alluvial fans, and fc is clayey floodplain alluvium.

The Late Wisconsin glaciation is described in the Hennepin County Geologic Atlas as the dominant force shaping the landscape around Staring Lake. According to the Geologic Atlas, “Hennepin County was completely covered by ice sheets of both domains [the Superior Lobe and the Des Moines Lobe] during the last glaciation. … Although the Superior Lobe once reached across Hennepin County and into Carver County, it apparently did not remain at its maximum very long, but retreated to a more stable position where it constructed the hills of the St. Croix moraine.” The St. Croix moraine lies just a bit to the north of Staring Lake, in those green till map units.

“While stagnant blocks of Superior lobe ice were melting, glacial ice from the Keewatin center moved into Hennepin County. This ice sheet, named the Des Moines lobe, … After the ice sheet retreated to downtown Minneapolis and west of the Calhoun chain of lakes, its meltwater laid down a broad outwash plain (unit do) fed by several large streams moving across and within the stagnating ice and draining through the St. Croix Moraine. … The Eden Prairie outwash plain also was laid down at this time, but over silty sediment from an earlier lake trapped between the moraine and retreating ice. A minor readvance of the Des Moines lobe laid a thin layer of till over the western part of the Eden Prairie outwash.The pitted character of parts of both outwash plains reflects continued melting of ice after deposition ceased and collapse of outwash already in place. Small ice-walled lakes (unit dlc) formed on drainage divides where no outlets were available to the major meltwater streams. (Hennepin County Geologic Atlas, 1989).”

Based on this, as best I can tell, Staring Lake is probably one of the small ice-walled lakes described in the above text, though Purgatory Creek has, during the Holocene, created both an inlet and outlet for the lake. The geologic atlas goes on to say: “Most of the lakes and bogs in Hennepin County are in depressions created by eventual melting of buried remnants of the two last ice advances.” The atlas concludes, “Lakes and bogs are filling in with sediment and organic debris (units ld and o). Human activity in places has speeded up the process (unit od).”

The Minnesota River Valley is probably the most prominent topographic feature of the Minneapolis region, and that’s got its own glacial and post-glacial story to tell. But that will have to wait for another day. For it’s a scenic Saturday afternoon here in North Carolina, and there are pumpkins waiting to be picked.

Comments (2)

Links (2)-

-

Pingback: Our Highly Allochthonous travels in 2011 | Highly Allochthonous

Pingback: How I use “new media” « Watershed Hydrogeology Blog