![]() The magnitude 6.3 earthquake that stuck central Italy near the city of L’Aquila in April 2009 killed more than 300 people, made tens of thousands more homeless, and caused billions of Euros’ worth of damage. No-one could have predicted exactly when it would strike, or how large it would be when it did, because you can’t predict earthquakes. And yet, despite this, six Italian seismologists and an official of Italy’s Civil Protection Agency are in the process of being prosecuted for the manslaughter of those killed in the earthquake. In Italy at least, it seems you can be held accountable for failing to predict the unpredictable.

The magnitude 6.3 earthquake that stuck central Italy near the city of L’Aquila in April 2009 killed more than 300 people, made tens of thousands more homeless, and caused billions of Euros’ worth of damage. No-one could have predicted exactly when it would strike, or how large it would be when it did, because you can’t predict earthquakes. And yet, despite this, six Italian seismologists and an official of Italy’s Civil Protection Agency are in the process of being prosecuted for the manslaughter of those killed in the earthquake. In Italy at least, it seems you can be held accountable for failing to predict the unpredictable.

The case being brought hinges on a meeting that took place on 31 March 2009, one week before the L’Aquila earthquake hit. Just prior to this there was a swarm of earthquakes in the magnitude 3-4 range in the region, and this seems to have been enough to prompt the Italian Civil Protection Agency to confer with Italian seismologists, to clarify if these tremors were a prelude to a bigger earthquake. In a press conference following this meeting, Bernardo De Bernardinis (the accused Civil Protection Agency official) said:

The scientific community tells me there is no danger, because there is an ongoing discharge of energy. The situation looks favourable.

This statement seems to imply – incorrectly – that the small earthquakes felt up to that point reduced the risk of a larger earthquake later. In fact, they would have had only a minor effect on the stored regional strain that was eventually released by the L’Aquila earthquake. However, misleading as this statement is, it does not appear in the minutes of the meeting: it seems we’re probably looking at De Bernardinis’ own confused interpretation of what the seismologists told him (I wonder – and this is pure speculation – if they were discussing how the swarm that prompted the meeting seemed to be dying down).

However, there is a far more fundamental problem. The implication at the heart of the prosecution’s case is that the press conference should have proclaimed the opposite: that there was a risk of a big earthquake in the coming days. If they had, the prosecution claims, then people in the area would have taken the last minute precautions that would have saved more lives, if only the accused hadn’t translated “their scientific uncertainty into an overly optimistic message”. The problem with this line of reasoning is that there was no basis for saying such a thing based on the information available at the time. The small earthquakes in the week before the L’Aquila main shock may well have been foreshocks, but there’s no way of knowing this in advance; there is nothing inherently ‘fore-shocky’ about foreshocks, it’s just a classification made in hindsight.

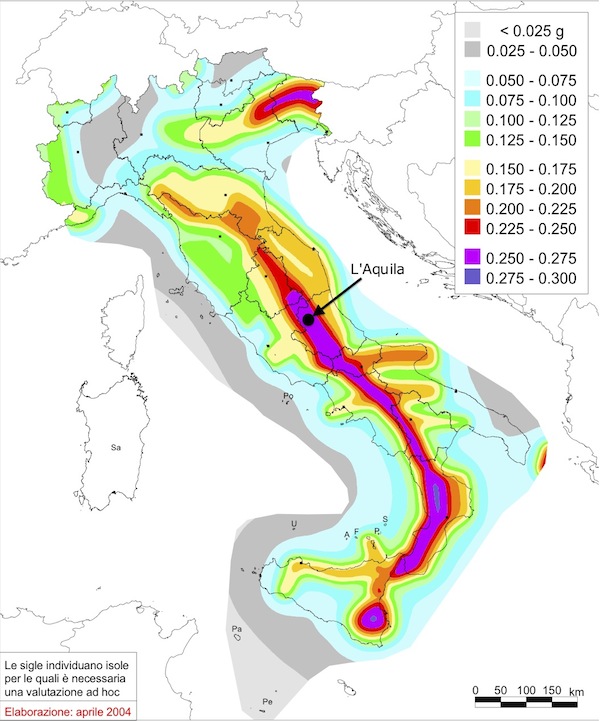

The message the seismologists probably wanted to convey (and, admittedly, failed to) was that there was no immediate danger – beyond the normal risks associated with living in a tectonically active region. In Italy, events like the 2009 earthquake are no surprise at all: since 1900 the country has been stuck by 11 magnitude 6 or greater earthquakes, including the 1915 Avezzano earthquake, only 30 km or so south of L’Aquila, that had an estimated magnitude of 7 and killed more than 30,000 people. Italy’s equivalent of the USGS or BGS, the INGV, produced this map of the seismic hazard in 2004. Guess which city falls smack bang in the middle of one of the areas of highest risk?

Seismic hazard map for Italy, showing the peak ground accelerations that have a 10% chance of being exceeded in 50 years. Source: INGV.

This is the real crux of the issue: for those living in L’Aquila, a damaging earthquake was inevitable. And, given that there is no reliable method of short-term earthquake prediction, waiting for some sort of official warning so that you could then rush around like a headless chicken is not a good strategy. What you need to do is acknowledge you live in a seismically active area, and be prepared for the earthquakes that are a consequence of this, whenever they chose to strike. For the authorities, this means setting and enforcing building codes, improving the resilience of vital infrastructure, and making sure clear emergency response plans are in place. For the general populace, it is about making sure you know how to best protect yourself when your house starts shaking.

This prosecution distracts from this message, and plays to the misguided idea that there was something concrete for the Italian seismologists to miss, or play down, in the run up to L’Aquila earthquake – something that should have prompted an explicit warning. There wasn’t. This is just another example of the perennial problem when talking about earthquake risks. The public wants to be told that they might not want to be in the area next Friday; all a seismologist can justifiably say is that if you hang around for the next 50 years, you’ll definitely feel something. Probably.

Comments (1)