![]() It turns out that, by US standards at least, I’m quite close to the Driftless Area that Anne posted about earlier this week. But unlike that corner of Minnesota, Illinois is whatever the opposite of ‘driftless’ is: it was covered by ice 20,000 years ago, and was blanketed with a thick layer of sediment released from that ice as it melted over the next 10,000 years or so. Because sediment tends to fill in all the low bits of the landscape first, the end result of this inundation is unlikely to inspire people to break out their rock climbing gear (there is, of course, some topography in the form of the Great Lakes, which have been filled in by water rather than sediment).

It turns out that, by US standards at least, I’m quite close to the Driftless Area that Anne posted about earlier this week. But unlike that corner of Minnesota, Illinois is whatever the opposite of ‘driftless’ is: it was covered by ice 20,000 years ago, and was blanketed with a thick layer of sediment released from that ice as it melted over the next 10,000 years or so. Because sediment tends to fill in all the low bits of the landscape first, the end result of this inundation is unlikely to inspire people to break out their rock climbing gear (there is, of course, some topography in the form of the Great Lakes, which have been filled in by water rather than sediment).

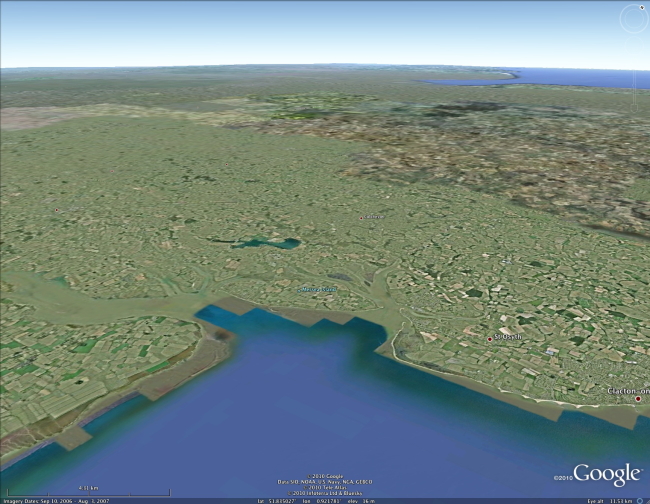

This is hardly the first time that I’ve found myself living in an area with a distinct lack of inspiring topography. For the first 21 years of my life, I lived in East Anglia, a region of the UK whose maps are well known for marking hills scarcely worthy of the name.

Northern Essex and Suffolk, looking NW.

East Anglia is flat for the same reason Illinois is flat – it is covered in gravels, sands, and muds laid down by melting ice sheets – although in Southern England most of this drift was deposited a few glacial cycles before the last one.

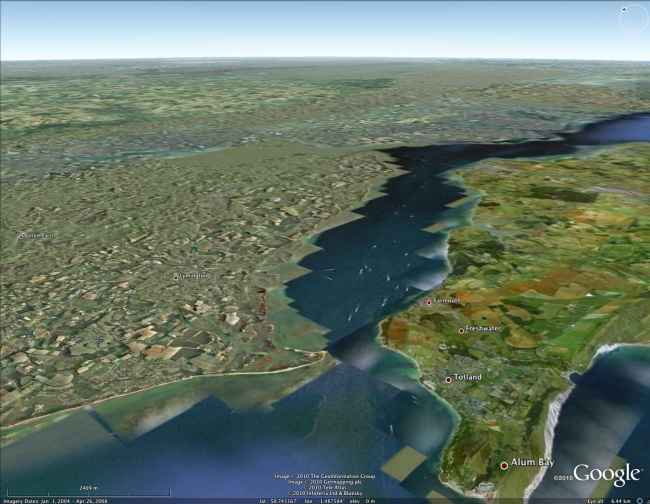

I studied for my PhD in Southampton, on the south coast of England. Hampshire is not quite as flat as East Anglia, but it’s still only mildly hilly.

Southampton, the Solent and the Isle of Wight (right). Looking ENE.

However, the flatness here is nothing to do with glacial deposits; bedrock is at or close to the surface over much of the region. However, that bedrock is mainly chalk, with some clays. With these weak and crumbly rocks underfoot, you’re never going to get topography more dramatic than the rolling hills of the Downs.

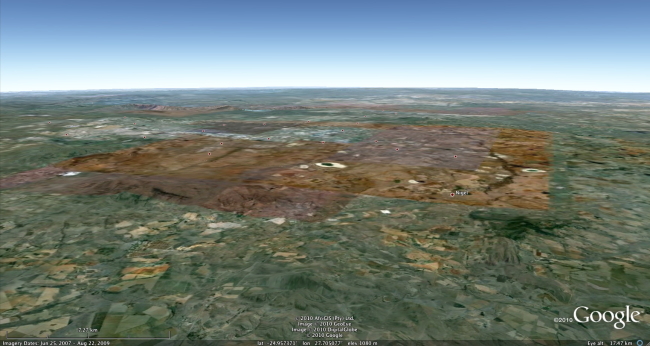

After Southampton, I moved a bit further afield, to Johannesburg. The quartzite ridges of the gold-bearing Witwatersrand Formation aside, the amount of relief is surprisingly low when you consider you’re at an altitude of 1750 m, and situated mostly on hard, old granites, volcanics, and sandstones. But these hard, old rocks have sat there for hundreds of millions of years, having most of their rough topographic edges smoothed off by hundreds of million years of erosion (the high elevation is a more recent development, a result of hot upwelling mantle beneath the African continent). The flatness here is not due to recent sedimentation, or lithology, but time.

Johannesburg, looking NW.

Geologists like mountains. I’ve often grumbled about how, with the honourable exception of Edinburgh, I’ve often ended up living a long way away from any peaks; and, by implication, the cool geology. It’s not true, of course. But I haven’t really considered before how just as there are many ways that a landscape can end up being pointy, there are several ways that it can end up being flat.

Comments (4)