![]()

![]() Palaeoblogger extraordinaire Brian Switek has often expressed frustration at the fact that many recent popularisers of evolution have a habit of downplaying the importance of the fossil record in studies of evolution. However, when reading the opening chapters of Written in Stone, Brian’s thoughtful and engaging attempt to bring fossils back to the center of evolutionary theory, you can’t help but wonder if, to a certain extent, palaeontology marginalised itself. When Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, palaeontologists did not exactly welcome his vision of life’s gradual evolution by natural selection with open arms. Some of the general scepticism was at least partly fuelled by a conflict with their religious beliefs; Richard Owen and Charles Lyell were notable examples of this. But it can’t have helped matters that Darwin went out of his way to point out the imperfections of the fossil record, the focus of their lives’ work. Darwin’s vision matched up in a broad sense to the narrative of life’s history written down in the geological record, but at the level of individual species, the gradual transitions expected if natural selection were at work were not so readily apparent. Darwin argued that what were at first glance geologically rapid disappearances of old species, and relatively abrupt emergence of new ones, was more a reflection of the incompleteness of the rock record than of what was actually occurring during these transitions.

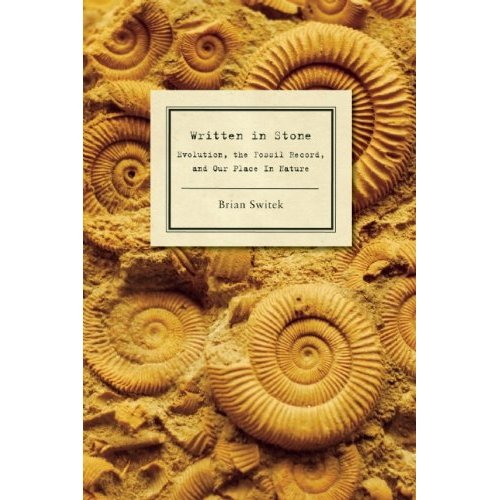

Palaeoblogger extraordinaire Brian Switek has often expressed frustration at the fact that many recent popularisers of evolution have a habit of downplaying the importance of the fossil record in studies of evolution. However, when reading the opening chapters of Written in Stone, Brian’s thoughtful and engaging attempt to bring fossils back to the center of evolutionary theory, you can’t help but wonder if, to a certain extent, palaeontology marginalised itself. When Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, palaeontologists did not exactly welcome his vision of life’s gradual evolution by natural selection with open arms. Some of the general scepticism was at least partly fuelled by a conflict with their religious beliefs; Richard Owen and Charles Lyell were notable examples of this. But it can’t have helped matters that Darwin went out of his way to point out the imperfections of the fossil record, the focus of their lives’ work. Darwin’s vision matched up in a broad sense to the narrative of life’s history written down in the geological record, but at the level of individual species, the gradual transitions expected if natural selection were at work were not so readily apparent. Darwin argued that what were at first glance geologically rapid disappearances of old species, and relatively abrupt emergence of new ones, was more a reflection of the incompleteness of the rock record than of what was actually occurring during these transitions.

It is certainly true that the geological record is fundamentally patchy. A large amount of the time recorded by even the most rapidly deposited sedimentary rock is marked by periods of non-deposition, or even erosion. But perhaps palaeontologists would have been less defensive if Darwin had placed more emphasis on the fossil record being incomplete in another sense. Geology was still a fairly young science, which meant that the types and ages of the rocks in many areas, particularly outside of Europe, remained very poorly known. If such basic geological facts were lacking, some of the gaps in the fossil record could potentially be filled, by the many new fossil forms that were undoubtedly hiding in these uncharted sequences, waiting to be discovered. In Written in Stone, Brian expertly describes how over the last century and the half, new discoveries have indeed filled in the details of some of the most important transitions in the fossil record: how the descendents of a group of Devonian fish became land-dwelling tetrapods; how the distant ancestors of mammals were the first terrestrial vertebrates to flourish, before giving way to the dinosaurs in the aftermath of the Permian extinction; how the end-Cretaceous extinction allowed what had now become mammals to flourish again, with some of them (whales and dolphins) returning to the ocean once more. It describes our growing understanding of the dinosaurian ancestry of birds – including the fact that feathers long predated the evolution of flight – and our species’ own messy emergence from a tangled family tree of fossil hominids.

Indeed, one of the important messages of this book – and through it, the fossil record – is that evolution is messy. There is no linear ‘March of Progress’, with a simple succession of related forms linking the old lineage with the new. Instead, a radiation event produces a bewildering array of evolutionary brothers, sisters, and cousins, all living at the same time. Natural selection then gradually prunes away at this diverse family tree until only a few isolated branches are left to carry on alone. The chapters on horses and mammoths are particularly effective in communicating this more nuanced view of evolution, which is vital for properly understanding our own recent evolutionary history.

But this is not the only area where Brian cleverly paints a more messy, yet accurate, scientific picture for the reader. The scientific process itself also suffers from being viewed through the lens of the ‘March of Progress’ – as nothing but a line of successful discoveries sequentially building on each other over time. Those of us who practice science know that this is a long way from the truth: any scientific step forward is usually preceded by several steps back and sideways, and a great deal of arguing over the map. Each of the chapters in Written in Stone not only describes an evolutionary transition, but also how our understanding of that transition has itself evolved over the past 150 years, as new discoveries have rewritten what we thought we knew. There is often an interesting sense of acceleration: as palaeontology has matured, it has got to the stage where the act of discovering a new fossil simply provides a target for a bewildering array of new analytical techniques that can begin to unravel its secrets. But the reader also gets a compelling narrative of the scientific mis-steps, the dead ends, the characters and egos that have, in turn, driven palaeontology forward, sent it off course, or even blocked it.

Written in Stone is a true treasure trove; everyone who reads it will learn a great deal about the fossil record and palaeontology. Yet almost as valuable is the fact that Brian has not just revealed evolution in all its untidy glory, but the scientific process itself.

Comments (1)