![]() It seems that pictures like this are not enough for some people:

It seems that pictures like this are not enough for some people:

The millions of barrels of oil that have leaked from the blown out Macando well in the wake of the Deepwater Horizon disaster are going to disrupt the ecology and economy of the entire Gulf of Mexico for months and years to come. But it seems that we shouldn’t be worrying about that. No, what we should be worrying about is the eruption of a giant, 20-mile wide methane bubble from the seabed, generating a megatsunami that would wipe out most people in the Gulf region and poisoning any survivors, before going on to poison the rest of the planet, too.

If anyone is wondering whether this is a credible threat, the only polite answer is an emphatic ‘no’. The facts being warped beyond breaking point to generate this ludicrous scenario are as follows:

- There is probably a lot of methane gas stored in the deepwater sediments of the Gulf of Mexico. But it is not free gas. It is in the form of clathrates, or gas hydrates, which are a form of ice that traps a lot of gases like methane into a solid lattice. Hydrates generally occur in small patches that are widely spread throughout the sediment, rather than in one huge blob. The large volumes that are talked about are due to the large areas of the continental slope where the temperature is low enough, and the pressure high enough, to allow clathrates to form. The idea that there is a huge, continuous, high pressure reservoir of gas beneath the sea floor, just waiting to explode, is fundamentally mistaken. If there was, do you think BP would drill through a vast, easily obtainable hydrocarbon resource to get to a more technically challenging reserve?

- It is also true that gas hydrates are not particularly stable. A small decrease in pressure or increase in temperature can cause them to break down and release the gas that they are storing. Indeed, it has been theorised that destabilisation of the clathrates around the well, due to heat released by the curing of the cement seal, is what caused the well to blow out in the first place. Could continuing clathrate breakdown in the region around the well account for the high amounts of methane coming from the leaking well? It’s possible, but as far as I know still unproven. More importantly, only a vanishingly small percentage of the clathrates, the ones immediately surrounding the borehole, are going to be at all affected by its presence. To release the catastrophic amounts being proposed requires a basin-wide change due to warming of the bottom waters or a drop in sea level. Even BP haven’t screwed things up that much.

- Even if a large volume of clathrates was somehow destabilised (which, as I’ve just pointed out, is not going to happen in this case), you still wouldn’t get a single, apocalyptic, megatsunami-generating explosion.That would require large amounts of gas being produced in a small volume much faster than it can escape, so very high pressures can build up in the surrounding rock and blow it apart from within (this is what happens in an explosive volcanic eruption). In this case, the gas hydrates are in sediments that are just beneath the sea floor, which aren’t even truly rock yet – more like a thick and soupy mud. Because of this, they are fairly permeable to fluids and gas migrating through them, so any gas that is being produced can mostly escape up through the sea bed before dangerous pressures can build up. And because the clathrates are distributed over a large area rather than all being in one place, there will be many, many vent sites, not just one big one.

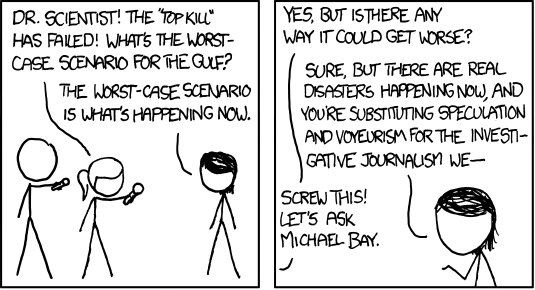

This doesn’t mean the methane being released from the leaking well isn’t worrying: in fact, it’s potentially a huge ecological problem for the Gulf of Mexico. Bacteria in the water column will happily respire it and use up all the oxygen, creating the ‘dead zones’ we’re hearing so much about. Seriously, isn’t reality bad enough? Do we really need to pretend we’re in a Michael Bay movie?

Comments (4)

Links (2)

-

-

Pingback: Geoblogospheric community. What is it good for? | Highly Allochthonous

Pingback: Geoblogospheric community: what is it good for? « Watershed Hydrogeology Blog