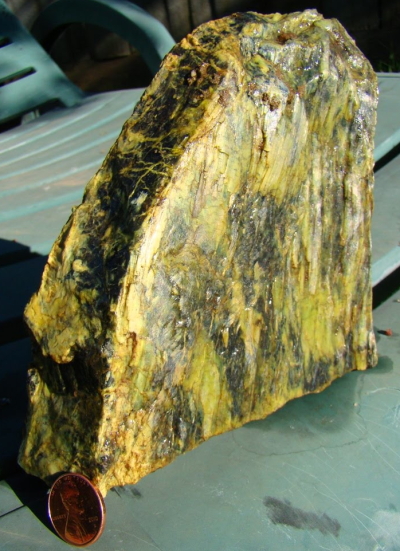

![]() Serpentinite is a very striking rock. olive green and glossy, even rather soapy to the touch when fresh, and a vibrant red when weathered, it’s easy to spot when you’re out in the field.

Serpentinite is a very striking rock. olive green and glossy, even rather soapy to the touch when fresh, and a vibrant red when weathered, it’s easy to spot when you’re out in the field.

Serpentinite is striking visually because it also has quite striking mineralogy. It has a very different composition from most rocks you find at the Earth’s surface: it is far richer in magnesium and poorer in silica. That’s because it wasn’t actually formed at the Earth’s surface, not really: it’s a piece of the Earth’s mantle, originally from 10 kilometres or more beneath the surface. The mantle is mainly composed of a rock called peridotite: if you bring some peridotite up from the mantle and add a bit of water you get the mineral serpentine, which is the principal constituent of the rock serpentinite.

As you might imagine, it takes some pretty extreme geological activity to bring material up from below the base of the crust to the surface. The presence of serpentinite is a badge of tectonic honour, a testament to the extreme deformation suffered by the places it is found. In Oman, it is found where a whole section of oceanic crust has been thrust up onto the continental margin, rather than being subducted under it as it usually is.

Weathered part of the lower crustal sequence, Oman ophiolite. Photo by C.J. Rowan, 2009

In the Alps and Himalayas, it is found even in the highest peaks, the merest trace of the once vast Tethys ocean that once separated Africa and India from Eurasia before being swallowed up by a vast and ongoing continental collision.

And you also find serpentinite in California – lots of it. It is the legacy of a time 30 million years ago when, instead of the western part of the state grinding northwards against the eastern side along the San Andreas Fault system, there was instead a subduction zone, where two plates pushed together. In the process, fragments of microcontinents, seamounts and other tectonic detritus was mashed into the eastern coast of California, creating a confusing collage of exotic terranes, and in some cases bringing deeply buried things – like serpentinite – to the surface. It’s presence is one of the major clues that California’s deformational past was very different from what is seen today.

Essentially, serpentinite is like a big red flag telling geologists, “interesting tectonic stuff here!” But in California, that might not be the only red flag that you will be seeing in the future, if the state government have their way. It turns out that serpentinite is California’s state rock (although they actually specify the mineral, serpentine, rather than the rock). As a Brit, I’m not entirely sure what that means, but it certainly hasn’t resulted in any general awareness of what serpentine is, what it represents, and – most importantly in this instance – what it isn’t. California Senate Bill SB 624 is intended to strike off serpentine as the state rock, claiming.

Serpentine contains the deadly mineral chrysotile asbestos, a known carcinogen, exposure to which increases the risk of the cancer mesothelioma.

This assertion is, to say the least, not quite accurate. Chrysotile is one of 20 serpentine group minerals. This variety means that chrysotile is not necessarily a significant constituent of every chunk of serpentinite. Furthermore, ‘asbestos’ is a descriptive term applied to a mineral’s habit, or physical shape – it means that the crystals are long and fibrous. Chrysotile is not the only asbestiform mineral, and whilst prolonged exposure to amphibole asbestos minerals such as tremolite and actinolite have been shown to be strongly linked to mesothelioma, no such link has been proven for chrysotile.

Of course, we can’t expect everyone to be up-to-date on their mineralogy (indeed, I had to look some of this up), and whilst it would have been nice if someone in the State Senate had bothered to check with some geologists before voting the bill through, it doesn’t really matter that much, right? Well, it would seem not: enshrining such erroneous information in law could have considerable legal consequences, given the common occurrence of serpentinite in California. Andrew Alden explains:

SB624’s sponsors are mesothelioma lawyers setting a trap by having the state declare that serpentine, in and of itself, is a carcinogen. This will allow them to rack up billable hours in court whenever anyone—a landowner who wants to shut down a noisy historic railroad line, the owner of a rural hilltop palace who wants developers out of his viewshed, opponents of a new highway—is willing to invoke the “A-word” asbestos on their behalf.

Something fishy is certainly going on with this bill, because as it turns out we shouldn’t be so quick to decry the California Senate’s geological ignorance. The bill they voted through was about composting; it was only after the vote that the bill’s sponsor, Senator Gloria Romero, inserted the anti-serpentine text. You can actually see it for yourself in the online records: compare the description for the bill between April 13 2009, and the description for May 19 2010. Again, as a Brit, I don’t really understand how that’s at all consitutionally valid, but whatever the legalities it certainly smells a little funny.

I’m a little late to this cause, and regular geoblog readers are no doubt aware of how, thanks largely to the efforts of the tireless Garry Hayes of Geotripper, the fuss about this bill has grown on Twitter and is now gracing the pages of the New York Times (if you do need to get up to speed, Silver Fox has a comprehensive collection of links). I can only agree with Garry that education is much better than litigation: actually teaching people about serpentinite will not only prepare them to use caution if they do come across any veins of chrystolite (although they’d have to be returning again and again to pound it up and inhale it to be at any real risk), but will also teach them about all the fascinating geological stories that the presence of serpentinite signposts.

So beware, Californians: if you’re not careful, Texas – blessed, lest we forget, with the stupidest school board this side of the Dark Ages – will be laughing at you. Laughing at you for wasting your time on a non-existent health threat from your state rock, when you have a few slightly bigger problems that need dealing with. But it’s not too late to save yourself from this ignominious fate. The bill has yet to come up to a vote in the California assembly, and there’s always the Governator to lobby – Garry Hayes’ excellent open letter would be a good place to start.

Comments (8)