![]() Before everyone was distracted by Eyjafjallajokull disrupting air travel and tongues alike, the geo-worry of the moment was not volcanoes, but earthquakes. So far this year there have been six earthquakes of magnitude 7 or greater, including the a devastating magnitude 7.0 quake in Haiti, a truly enormous tsunami-generating magnitude 8.8 off the coast of Chile (although fortunately, the tsunami hysteria was greater than the actual tsunami), and a 7.2 in northwest Mexico. Most recently, last week’s magnitude 6.9 in western China/Tibet also caused much damage and many casualties.

Before everyone was distracted by Eyjafjallajokull disrupting air travel and tongues alike, the geo-worry of the moment was not volcanoes, but earthquakes. So far this year there have been six earthquakes of magnitude 7 or greater, including the a devastating magnitude 7.0 quake in Haiti, a truly enormous tsunami-generating magnitude 8.8 off the coast of Chile (although fortunately, the tsunami hysteria was greater than the actual tsunami), and a 7.2 in northwest Mexico. Most recently, last week’s magnitude 6.9 in western China/Tibet also caused much damage and many casualties.

Whenever the world experiences what seems like a run of especially damaging earthquakes, people start to wonder if it has some long-term significance, with some seeing precursors of their impending apocalypse of choice. The USGS has clearly been fielding some questions about the perceived uptick in seismic activity, as last week they released a statement that in terms of earthquake frequency 2010 is so far on course to be a relatively normal year.

Scientists say 2010 is not showing signs of unusually high earthquake activity. Since 1900, an average of 16 magnitude 7 or greater earthquakes – the size that seismologists define as major – have occurred worldwide each year. Some years have had as few as 6, as in 1986 and 1989, while 1943 had 32, with considerable variability from year to year.

With six major earthquakes striking in the first four months of this year, 2010 is well within the normal range. Furthermore, from April 15, 2009, to April 14, 2010, there have been 18 major earthquakes, a number also well within the expected variation.

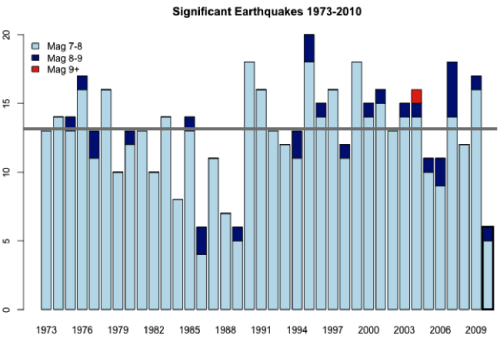

I thought this point could be best illustrated visually, so I ran a search through the USGS/NEIC earthquake catalogue for earthquakes of magnitude 7 or greater that have been recorded globally since 1973 (the starting point of the database). The results are plotted below. In the last 28 years, there have been on average around 13 such ‘significant’ earthquakes a year, with a magnitude 8 occuring about every year and a half. This average rate is marked by the grey line on the plot: if we extraplolate the six major earthquakes recorded in the first four months, 2010 is on course to experience 18 major earthquakes, a little above average but well within the variability shown by the whole dataset (and it’s actually closer to the centennial average of 16 major quakes a year reported by the USGS above).

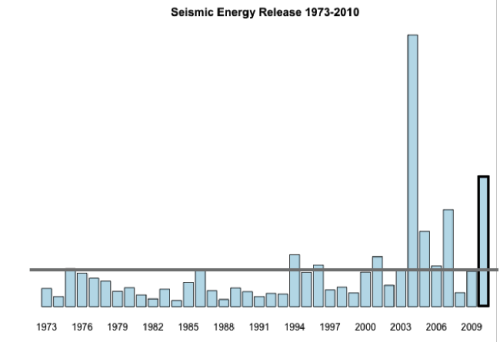

However, looking at earthquake frequencies may not be the best way to examine this issue. What we’re really interested in is the total energy being released by these earthquakes, and because the magnitude scale is logarithmic, a single magnitude 8 is responsible for releasing many times more energy than a magnitude 7. In fact, an increase of one unit of earthquake magnitude, which corresponds to a 10-times increase in the amplitude of the earthquake waves recorded by a seismometer, corresponds to a 32-times increase in the total seismic energy released. If you look at the frequency distribution on the graph above with that fact in mind, it immediately becomes clear that the relatively infrequent magnitude 8 and 9 earthquakes actually release far more energy than all those magnitude 7s. A plot of annual seismic energy release clearly shows this: there is a lot more year-on-year variability, because in some years there are one or two magnitude 8s and in others there are none, and there are too few magnitude 7s to make up the difference. The year that really stands out is 2004: it was only a slightly above average year in terms of earthquake frequency, but one of those quakes was the magnitude 9.1 Boxing Day earthquake off Northern Sumatra, which released as much energy as 1500 magnitude 7s, all in one go.

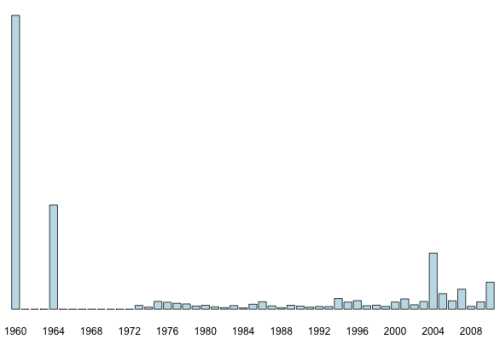

Interestingly, 2010 does stand out a bit on this plot thanks to that magnitude 8.8 off Chile, which is, behind the Sumatra earthquake, the 2nd biggest earthquake recorded since 1973. Indeed, if you’re willing to squint a bit, you might hypothesise that there does seem to be an increase in the rate of seismic energy release in the last 5 years. However, the significance of this is easily refuted by adding a couple of events from just before the NEIC catalogue starts: the 1960 Chile earthquake (magnitude 9.5), and the 1964 Prince William Sound earthquake (magnitude 9.2).

Effectively, the entire 27 years’ worth of seismic energy release recorded in the NEIC catalogue only represents about three quarters of the energy released by just these two earthquakes. So, if there was ever a time to announce the oncoming seismic apocalypse, the early 60s would have been the time to do it – even if you would then have had to cope with the embarrassment of us still being here. The problem is that the seismic rhythms of the planet operate over timescales much longer than a year, or even a decade. Over hundreds and thousands of years, there is some regularity to the seismicity in a particular area, driven as it is by tectonic forces that can remain relatively constant over millions of years. But we humans don’t see things on that broad temporal scale: instead we are stuck right in the temporal guts of a random process, giving the occasional large earthquake much more significance that it actually has in the grand scheme of things.

There is a slightly more subtle point here too. The seismic energy released so far this year was mostly due to just one earthquake: the magnitude 8.8 off Chile. Whilst it caused $30 billion of damage and killed more than 500 people, in terms of human impact it was dwarfed by the earthquake in Haiti – despite that quake releasing less than 1/500th of the energy. As Kim explained a while back, Port-au-Prince was right next to a shallow rupture, so the shaking due to the earthquake was extremely intense; in Chile, the fault rupture was deep and offshore, and by the time it had reached the towns and cities on the coast, the seismic energy had spread out, resulting in a wider region of strong, but not quite so intense, shaking.

So really, worrying about rates of large earthquakes is a little beside the point. For human populations and infrastructure it’s not so much a question of how much energy is being released, but where that release is taking place.

Comments (11)