![]()

![]() The further back in time we go, the more and more fragmented the Earth’s geological record becomes. Whilst not exactly common, rocks with ages up to about 3.5 billion years old are found at multiple points on the Earth’s surface. However, rocks older than this are much less common. Extensive outcrops older than about 3.8 billion years are exceptionally rare, possibly because a series of very large meteorite impacts prior to this time – the Late Heavy Bombardment – largely destroyed any older bits of crust. The Acasta Gneiss in northern Canada, dated at around 4.03 billion (4030 million) years, is generally regarded as the oldest known outcrop of crust, although a recent study has claimed that the Nuvvuagittuq greenstone belt, also in northern Canada, may be as old as 4280 million years. The only known bits of the Earth that are older are 4.2-4.4 billion year-old zircon crystals found in the Jack Hills Conglomerate in Australia; the conglomerate itself was deposited about 3 billion years ago, but it contains debris eroded from much older, and now long-vanished, bits of crust.

The further back in time we go, the more and more fragmented the Earth’s geological record becomes. Whilst not exactly common, rocks with ages up to about 3.5 billion years old are found at multiple points on the Earth’s surface. However, rocks older than this are much less common. Extensive outcrops older than about 3.8 billion years are exceptionally rare, possibly because a series of very large meteorite impacts prior to this time – the Late Heavy Bombardment – largely destroyed any older bits of crust. The Acasta Gneiss in northern Canada, dated at around 4.03 billion (4030 million) years, is generally regarded as the oldest known outcrop of crust, although a recent study has claimed that the Nuvvuagittuq greenstone belt, also in northern Canada, may be as old as 4280 million years. The only known bits of the Earth that are older are 4.2-4.4 billion year-old zircon crystals found in the Jack Hills Conglomerate in Australia; the conglomerate itself was deposited about 3 billion years ago, but it contains debris eroded from much older, and now long-vanished, bits of crust.

Two or three data points is not a hell of a lot to go on when trying to reconstruct the evolution of the early Earth, especially when the material involved is far from pristine (the Acasta Gneiss, being a gneiss. has been partially remelted, for example). It is therefore no surprise that the geological timescale for the period between the Earth’s formation, about 4.56 billion years ago, and the start of the Archean Eon, usually pegged at about 3.8 billion years ago, is rather lacking in detail. This period is usually referred to as the ‘Hadean’, which is more of a reference to the presumed conditions on the Earth’s surface than a subtle pointer to the fact that we don’t know what the hell was really going on.

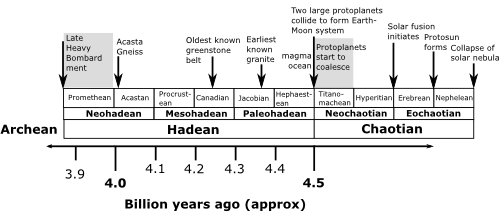

However, this has not stopped Colin Goldblatt and his co-authors having a go at adding a bit more structure to the Earth’s earliest days – and beyond. The ‘Chaotian’ eon at the start of their proposed new timescale is a common framework for the entire solar system, beginning with the gravitational collapse of the gas cloud that it would eventually form from. Key events – such as the initiation of solar fusion, or the first interactions between sizeable protoplanets that condensed from the protoplanetary disk – mark the boundaries between different eras and periods within the Chaotian. The start of the Hadean is marked by the collision of the proto-Earth, which the authors call Tellus, with another Mars-sized protoplanet, forming the Earth-Moon system.

Proposed new timescale for the formation of the solar system (Chaotian) and the evolution of the early Earth (Hadean). Click for a larger image

Thus, the Chaotian marks the time when solar system first became a distinct entity from the galactic neighbourhood; the beginning of the Hadean is when the Earth’s geological history begins to be shaped as much by internal processes, such as mantle convection, as by external events such as collisions with other protoplanets, Similarly, from beginning of the Archean, at the end of the Late Heavy Bombardment, internal processes start to completely dominate the Earth’s geological evolution; extraterrestrial collisions can still have significant geochemical and biological impacts, but they no longer melt the entire crust. Conceptually, I find this quite a nice way of looking at it.

The authors also attempt to subdivide the Hadean, but because we still don’t understand the key events in the Earth’s geological development over this period, it’s not quite as successful. The Hephaestean period probably covers the recovery from the Moon-forming impact. The Jacobian, Canadian and Acastan periods refer to the Jack Hills zircons, Nuvvuagittuq greenstone belt and Acasta Gneiss, respectively, but although these outcrops can give us clues about what the Earth was like when they first formed, it is a bit risky to try to characterise an entire planetary system from one sampling point. For example, the Jack Hills zircons tell us that granite – in other words, continental crust – was forming 4.4 billion years ago, but this is only a minimum age; we have no evidence that it wasn’t forming before that. Also, for all we know greenstone belts were also forming at exactly the same time, and have just not been preserved. The small amount of data we have available means that a single new outcrop might force the entire timescale to be redrafted.

It’s difficult to know if we’re ever going to be able to construct a truly robust, process based timescale for the first 700 million years of Earth’s history, because it’s unclear how much we’ll ever truly know about the Hadean. Still, this is an interesting attempt to set the story of our planet’s birth into a slightly more structured framework.

Goldblatt, C., Zahnle, K. J., Sleep, N. H., & Nisbet, E. G (2010). The Eons of Chaos and Hades Solid Earth, 1, 1-3

Comments (9)