![]() A magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck Haiti this evening, causing extensive damage to the capital, Port-au-Prince, and probably causing many casualties. The map below shows where the main shock occurred (red), as well as the epicentres of the numerous aftershocks (orange) that occurred in the following 5 or 6 hours (and continue even as I write).

A magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck Haiti this evening, causing extensive damage to the capital, Port-au-Prince, and probably causing many casualties. The map below shows where the main shock occurred (red), as well as the epicentres of the numerous aftershocks (orange) that occurred in the following 5 or 6 hours (and continue even as I write).

The main shock appears to have initiated less than 25 km southwest of Port-au-Prince; this close proximity meant that the city would have endured the maximum possible shaking intensity from an earthquake of this size, leading to extensive damage. Here’s the focal mechanism, courtesy of the USGS:

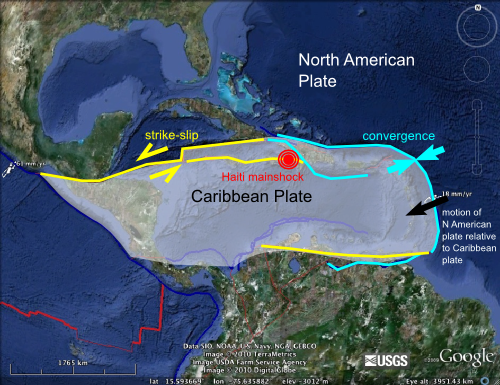

With the help of my recent post on focal mechanisms, it is hopefully obvious that the rupture occurred on a primarily strike-slip fault, with the crust on each side of the fault moving horizontally relative to the other side. To understand why there is strike-slip faulting in this area, we need to step back, and look at a simplied map of the entire Caribbean:

The Caribbean is contained on its own separate little plate; a rather diminutive part of the tectonic jigsaw that is the Earth’s crust. It is surrounded on three sides by the much larger North and South American plates, both of which are moving approximately westwards with respect to the Caribbean plate at around 2-3 centimetres a year. On the eastern edge of the plate, the boundary runs perpendicular to the direction of relative plate motion, so there is compression and subduction (and subduction volcanism, exemplified by the likes of Montserrat). However, as the boundary curves around to form the northern boundary of the Caribbean plate, where the Haitian earthquake occurred, it starts to run parallel to the direction of relative plate motion, making strike-slip faulting along E-W trending faults the most likely expression of deformation in this region. This is exactly what the Haitian quake appears to record.

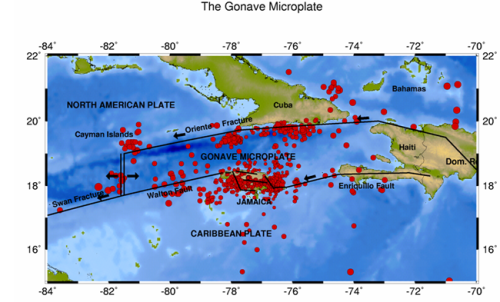

Note also that deformation across the northern plate boundary appears to be distributed – some motion is accommodated on faults that are located a little bit away from the actual plate boundary, further inside the plate interior. The Haitian quake appears to have occurred on one of these faults: based on the position of its epicentre the rupture is extremely close to the Enriquillo Fault, which appears to be a major strike slip fault running across the southern end of Haiti. This is the fault most likely to have ruptured.

Tectonic map of the Northern Caribbean (Source)

There is nothing particularly unusual about this earthquake given the tectonic context. Unfortunately, however, Haiti is a very poor country – one of the poorest and least developed in the world – so unfortunately, its government was not in a position to really do much to prepare for the inevitable large earthquake, leaving tens of thousands to suffer the consequences.

Update from Anne: Chris has been featured in a Nature News Briefing: “The Haiti Earthquake in Depth” along with more information about the faults in question and the known seismic risk of the area.

Further updates:

Haiti’s seismic future

What next for the Enriquillo Fault?

Comments (35)

Links (1)-

Pingback: Friday Focal Mechanisms: Haiti, revisited | Highly Allochthonous