On the 2nd day of Christmas my true love sent to me: 2 concordant zircons…

On the 2nd day of Christmas my true love sent to me: 2 concordant zircons…

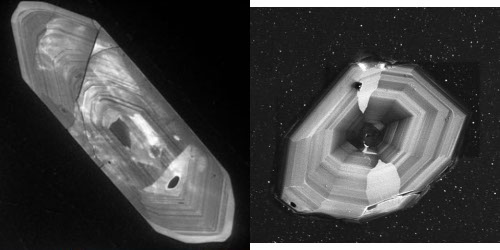

If you want to accurately date a rock, you really want to grind it up and extract some grains of zircon. This mineral has several useful properties: it is very hard and chemically inert, even at quite high temperatures, so will survive relatively intact even if the rest of the rock it is surrounded by is extremely squeezed, squashed and metamorphosed.

In addition, zircon’s crystal structure allows lots of uranium to be trapped within a grain when it forms, but virtually no lead. This doesn’t mean that you don’t find any lead within zircons if you chemically analyse them – you do. But this lead was produced within the crystal after it formed, by the radioactive decay of uranium. In fact, two different decay processes are at work: uranium 238 decays to lead 206, uranium 235 decays to lead 207. Therefore you have two ways of getting a radiometric age for the zircon: you can measure the ratio of uranium 238 to lead 206, or you can measure the ratio of uranium 235 to lead 207. This means that zircons have a built in cross-check: if you calculate the age using both of these ratios, and they are the same within error, the age is said to be concordant, and you can have more confidence that the age you have determined reflects the original age of formation (a resetting event would affect the different ratios to a different degree, and result in discordant ages).

We’re currently trying to extract some zircons – or baddeleyites, which are similarly useful for dating but more common in mafic rocks than zircons sometimes are – from the dykes I sampled in Oman last year. Of course, I could probably do with more than two, but two would be a start!

Comments (6)