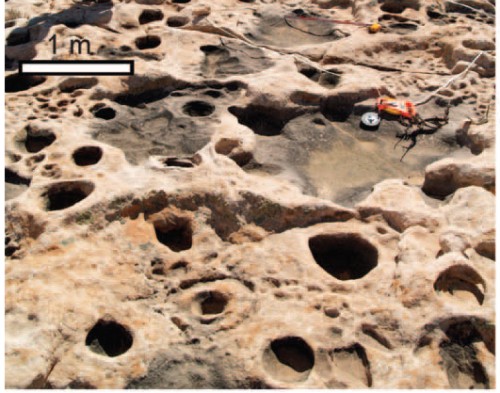

![]() If they weren’t being mentioned all over the place, these things would make a fine geopuzzle; I certainly wouldn’t guess that these things were dinosaur tracks. They look much more like potholes to me, and if If I came across this in the field, that would probably be what I’d call them. Which shows how much I know.

If they weren’t being mentioned all over the place, these things would make a fine geopuzzle; I certainly wouldn’t guess that these things were dinosaur tracks. They look much more like potholes to me, and if If I came across this in the field, that would probably be what I’d call them. Which shows how much I know.

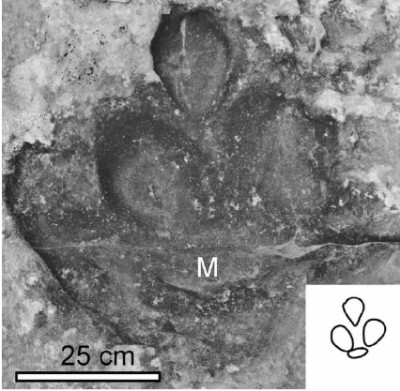

A more interesting question is, how do Winston Seiler and Marjorie Chan justify this interpretation? In their paper, they provide a number of reasons. The first one is that they “are of the proper size range”, which is a bit weak. Fortunately, they also provide more compelling reasons. For a start, about one sixth of the impressions that they studied in detail actually look like footprints.

Furthermore, there seems to be a morphological continuum from the clearer examples like this into various grades of “if you squint…”. In other words, if you look carefully, you can clearly see the obvious footprints are clearly just better-preserved versions of the less obvious ones. If they were weathering features, you’d probably expect a lot more randomly shaped, clearly unrelated impressions.

Another good indicator is that the floors of the “prints” are not flat, but slope in a fairly consistent direction. The shape and the consistency are both important. As the weight on your foot shifts when you push forward off a soft surface, the toe will push further down into the ground than the heel. If you have a track, the slope of every print should point in the direction of travel.

Finally, the way the rims have slumped and deformed suggest that these impressions formed early, before the mud became rock.

Thus, as if by magic, an ancient trampling ground for dinosaurs is revealed. It’s not magic at all of course, but a lot of careful study. To conclude that these things were footprints required the position, shape, and distribution of almost 500 of them to be carefully recorded. Without that sort of attention to detail, claiming dinosaur tracks would have had just as much support as calling them holes in the ground.

W. M. Seiler, M. A. Chan (2008). A Wet Interdune Dinosaur Trampled Surface in the Jurassic Navajo Sandstone, Coyote Buttes, Arizona: Rare Preservation of Multiple Track Types and Tail Traces PALAIOS, 23 (10), 700-710 DOI: 10.2110/palo.2007.p07-082r

Comments (2)