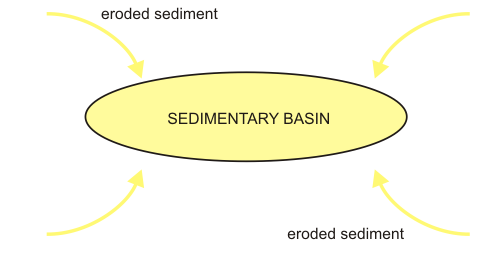

Sedimentary rocks are deposited wherever there is a hole that needs filling in. This hole – a sedimentary basin – can be created by tectonic events such as rifting, slower thermal subsidence caused by cooling of the crust (which increases its density), or things like a rise in sea level.

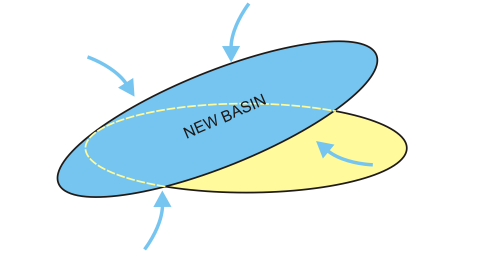

However, on a tectonically active world such as ours, it doesn’t stop there; later events both cover up and dismember the original sequence. Perhaps another rifting event forms a newer sedimentary basin, covering up the older rocks.

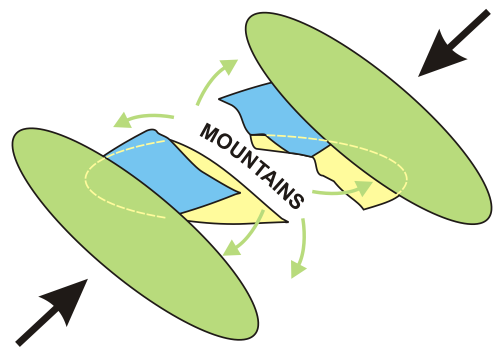

Later, perhaps a plate collision uplifts these rocks into a chain of mountains, and large sections are eroded back down to the original bedrock, removing any sign that they were there at all, as the ancient sediments are recycled and redeposited in new basins further away.

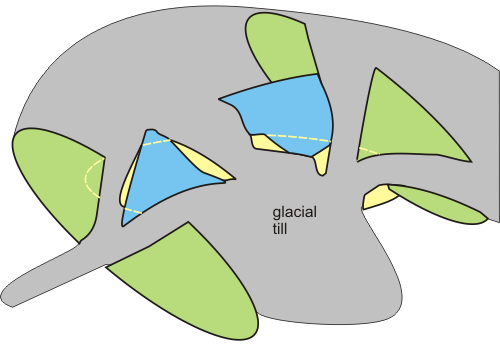

Later still, perhaps an ice age produces giant glaciers that grind away all but a few scattered remanents, and cover most of the rest with the detritus when they finally retreat.

When presented with the outcrop pattern in the final figure, would it be obvious that all the yellow blobs were once part of the same sequence, deposited in the same basin? Not without the handy colour coding, it wouldn’t. Connecting up all these different outliers requires lots of detailed study, looking for common patterns of changes in sediment type, geochemistry, and fossil content. And the older the rocks are, the more difficult making these connections gets. The lack of fossils in Precambrian rocks closes one of the more reliable routes to correlation. Older sequences also tend to be more fragmented, and have usually been subjected to many tectonic and volcanic episodes which might have altered the same rocks in very different ways, depending on where they are found. Some information, such as the full extent of the basin, and the processes which formed and filled it, might have been forever lost. So, for a geologist, reconstructing a picture of worlds long past is like trying to solve a jigsaw puzzle where most of the original pieces have been removed, and sometimes replaced with pieces from another puzzle entirely. Trying to work out which pieces are which is just as vital as working out the picture they are part of.

Comments (3)