In the wake of this weeks rather spectacular eruptions of the Chilean volcano Chaitén (which is being well-covered by the Volcanism Blog; more cool photos are available here, and at NASA’s Earth Observatory), a commentator has asked for some clarification on “how geologists classify volcanoes as active, dormant or extinct.”

In the wake of this weeks rather spectacular eruptions of the Chilean volcano Chaitén (which is being well-covered by the Volcanism Blog; more cool photos are available here, and at NASA’s Earth Observatory), a commentator has asked for some clarification on “how geologists classify volcanoes as active, dormant or extinct.”

The simple answer to this question goes thusly:

- An active volcano is one that is presently erupting (or at least growling a lot, with lots of seismic and thermal activity).

- A dormant volcano is currently inactive, but could feasibly erupt in the future.

- An extinct volcano is one that is both inactive and unlikely to erupt again in the future.

In many ways, I’m not sure that this classification is actually very informative, because these categories turn out to be rather fuzzy and tricky to determine. Even what constitutes a ‘presently active’ volcano is a little problematic: a cycle of magma chamber recharge and eruption occurs over geological timescales, so it makes little sense to only include volcanoes that have erupted in the past week, month or year (or even the past decade or century). For this reason, places such as the Smithsonian’s Global Volcanism Programme put any volcano that has erupted in recorded human history, or in the Holocene (the last 12,000 years or so), onto the active list.

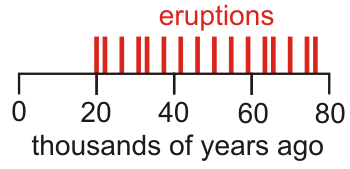

The division into ‘dormant’ and ‘extinct’ is also tricky, because what you need is some idea of a volcano’s eruptive history; not just the date of its last eruption, but the number and frequency of eruptions over a longer time. For example, lets say that you can date the last eruption of a particular volcano to 20,000 years ago, and dating of older lava flows shows that prior to that time there were eruptions every couple of thousand years or so:

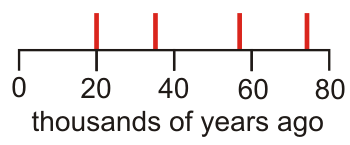

In this case, several eruptive cycles have been and gone since the last eruption, and we might be justified in saying that this volcano is extinct. In contrast, we might find that the eruptions are much more infrequent, say every 15,000 years or so:

In this case, we are still within the timeframe required for one eruptive cycle, and the magma chamber could still be refilling as a prelude to the next explosion. More detailed examination – trying to seismically image the magma chamber, or looking for gas emissions or hot springs, might give us some clues about whether your friendly neighbourhood mountain is dead, or merely dozing.

The problem, of course, is that for many of the world’s volcanoes this long-term information is just not available. If we look at Chaitén’s eruptive history, there was only one known eruption prior to this week’s pyrotechnics, which has been dated to around 10,000 years ago. The eruption has been described as a ‘surprise’, but in fact we don’t know enough to know if we should be surprised or not.

Comments (7)