![]() Anthropocene! Naming a new geological time period after ourselves certainly has a nice dramatic ring to it, even if it smacks of the hubris that got us into our current climatic mess in the first place. But can our species, as The Straigraphy Commission of the Geological Society of Londo claim in the GSA Today paper that everyone is talking about (update: Brian and Greg has also contributed enlightening perspectives), really justify claiming a place on the geological timescale?

Anthropocene! Naming a new geological time period after ourselves certainly has a nice dramatic ring to it, even if it smacks of the hubris that got us into our current climatic mess in the first place. But can our species, as The Straigraphy Commission of the Geological Society of Londo claim in the GSA Today paper that everyone is talking about (update: Brian and Greg has also contributed enlightening perspectives), really justify claiming a place on the geological timescale?

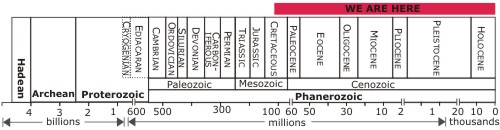

To properly evaluate this claim, we first need to understand the reasoning behind the present subdivisions of the geological timescale, which is something that I’ve touched on before:

The overarching goal of Geology as a science is to reconstruct the history of the Earth, and each of the geological periods can be considered chapters in this story; each one has its own distinctive characters – the form and diversity of life – and setting – the climate and the configuration of the continents.

The character of the Earth at any point in time is determined by a complicated interaction between many different forces, including tectonics, climate, and even life. As these different forces work with and against each other, an equilbrium of sorts can eventually be reached: for millions or even tens of millions of years, the same climatic cycles and temperatures prevail, the same species dominate in their various habitats, and the same sorts of depositional processes and patterns predominate in the various sedimentary basins around the world. Things are far from being static, but if you jumped half a million years ahead within such a period you would still recognisibly be on the same planet.

However, this equilbrium is unstable – the forces that control it cannot, and do not, remain constant over time. An ocean basin opens or closes, mountain belts rise, or sea levels fall, and suddenly the uneasy balance is disturbed; the Earth has to find a new geological equilbrium, and the climate, biosphere and depositional patterns may change significantly as it does so. Now if you jumped forward half a million years, you may imagine yourself to have travelled to another world entirely, so little is there left to remind you of the Earth that was.

So, to a first order, the various subdivisions of the geological timescale represent periods of time that have their own distinctive geological and biological character, with the boundaries being drawn within the periods of flux as the Earth adjusts itself to a new geological reality. Deciding on the details of these subdivisions is a much more subjective process, however. How important is a particular change – does it represent a new epoch? A new period? A new eon? And where do you mark the boundary when a shift to new conditions occurs over timescales of hundreds of thousands of years or more? Is it even practical – is there a suitable horizon in the fossil or geochemical record associated with the shift, that allows it to be reliably identified across different sequences worldwide? Such questions can lead to huge spats, such as the current Quaternary kafuffle. My feelings on this particular question are mixed: on the one side, there’s lots of historical baggage associated with the Quaternary – it’s original definition was something along the lines of ”all the stuff that isn’t rock yet’, which is hardly a great starting point if you’re trying to find a more technical description. On the other hand, this pedantic zeal to purge it completely from geological usage seems a little bit over the top: why not just say that it’s an informal equivalent to the Pleistocene and Holocene, and leave it at that? Of course, I have my own issues with having the Holocene as a division of equal rank with, and hence separate from, the Pleistocene – it’s just another interglacial as far as I’m concerned.

So what of the Anthropocene? In the GSA Today paper Jan Zalasiewicz and his co-authors present clear evidence (excellently summarised by Callan) that following the Industrial Revolution, as our population and demand for energy, fed mainly by burning fossil fuels, have soared, so has our impact on the global environment. We have now reached the point where we are going to have a clear impact on the geological record; the changes in sedimentation patterns, the disappearances or changes in distribution of various plant and animal species, and the effects of ocean acidification are all going to leave their mark.

The real issue is that the nature and impact of these changes is far from clear – the Earth is still a long way from fully responding to what we have wrought, and it’s still not clear how different and distinct the new geological reality is going to be from what has come before. If we stall the cycle of ice ages and interglacials, then perhaps we should draw a line under the Pleistocene and Holocene and define a new epoch. But what if the ice caps melt completely? Or the rate of species extinction continues to deplete the biosphere? Or we have now entered an age when human activity has permanently overwhelmed the more sedate geological controls on the state of the planet? If this happens, we could justify drawing a line under the Neogene, or the Cenozoic, or even (if we’re going to get really grand and sweeping about it) the Phanerozoic itself. Alternatively, if we get our act together and moderate our environmental impact, or if the climatic changes that we are forcing manage to cripple human civilisation (the real risk of climate change, as I have stated many times before), a brief excursion could reverse itself within a few tens of thousands of years, and the planet could return to a state indistinguishable from the Pleistocene (although you can’t reverse the extinctions). What do you call it then? Perhaps future geologists will puzzle over the weird “Anthropocene member” found around the world, where the planet seemed to go mad for a short period.

It seems to me that not only is the form of the timescale pretty subjective, but also that it only really be decided upon in hindsight. There’s something endearingly optimistic in the idea that our civilisation is going to stick around for long enough that this issue is going to be relevant; but in many ways, the need for an Anthropocene would be a testament to our failure to get our environmental act together.

Zalasiewicz, J., Williams, M., Smith, A., Barry, T.L., Coe, A.L., Bown, P.R., Brenchley, P., Cantrill, D., Gale, A., Gibbard, P., Gregory, F.J., Hounslow, M.W., Kerr, A.C., Pearson, P., Knox, R., Powell, J., Waters, C., Marshall, J., Oates, M., Rawson, P., Stone, P. (2008). Are we now living in the Anthropocene. GSA Today, 18(2), 4. DOI: 10.1130/GSAT01802A.1

Comments (8)