Mid-ocean ridges are a fundamental component of the Earth’s tectonic engine: they mark places on the earth’s surface where two plates are moving apart, creating space for mantle rocks to move upwards, decompress, and melt. Every year, the resulting volcanic activity produces around 20 cubic kilometres of new ocean crust. However, our current understanding of the details of this process – exactly how the melt gets to the surface, and how and when it erupts when it gets there – is still rather hazy. The problem is that all the action is taking place beneath 2 or 3 km of seawater, making it quite difficult to monitor what’s going on. There are also tens of thousands of kilometres’ worth of ridge to choose from, so finding the section that are currently volcanically active is rather like trying to find a needle in a haystack – whilst blindfolded.

It follows that any information about the scale and characteristics of mid-ocean ridge eruptions is pretty valuable; and this is exactly what a new paper in Geology by Soule et al. provides us with – a nice snapshot of a recent volcanic eruption on the East Pacific Rise.

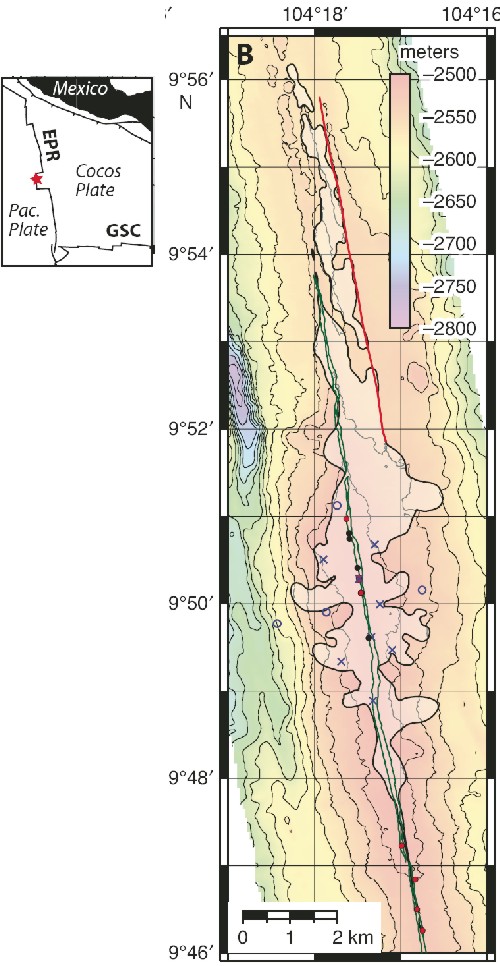

This particular eruption hit the news last year due to the rather unusual manner of its discovery: scientists found that several seismometers that they were trying to recover from this part of the ridge axis were refusing to budge, as a result of being engulfed in freshly-erupted basalt (they are marked by crosses in the figure above). This is actually not as much of a coincidence as it might seem: an eruption had been observed on this section of the East Pacific Rise in the early 1990s, and changes in hydrothermal vent chemistry and earthquake activity indicated that a further eruption might be imminent, so the seismometers had been deployed specifically in the hope that they might observe the seismicity leading up to, and associated with, the predicted eruption which eventually buried them.

The above map was built up using a special camera system which can be towed just above the ocean floor, taking detailed images as it goes. Because less than a year had elapsed between the eruption and the surveys, it was easy to spot the fresh black lava, because it had yet to be covered by sediment settling out from the ocean above.

(image source)

As the map shows, the flow is fairly large, covering almost fifteen square kilometres. It is also quite irregular in shape, with multiple lobes extending several kilometres away from the ridge axis; this might indicate that the lava was being simultaneously erupted from several different vents and fissures. Interestingly, the total volume of magma released by this eruption (including the fraction which didn’t make it all the way to the surface) is less than <15% of the melt held by the magma chamber beneath the ridge axis; this suggests that in this part of the ridge at least, the crust builds itself up through more frequent small eruptions rather than more widely spaced, larger ones.

This sort of study is exactly what Brian is talking about. There’s nothing Earth-shattering here, but by gradually pooling together the detailed observations from many studies like this, we will eventually know enough to understand the bigger picture of how oceanic crust is put together.

Soule et al. (2007), Geology 35(12), p1079-82 [doi]

Comments (1)