Error lies at the heart of science; but there are a number of different kinds of “wrong”. An error in hindsight, where a past hypothesis of yours – perfectly reasonable at the time – is disproven by more accurate or complete measurements, or the discovery of unappreciated complexities in the system you’re studying, is just part of the scientific process, even if many scientists have trouble acknowledging such errors. An interpretive error – making questionable inferences from your experimental data, or wrongly using extant knowledge from other sources – is more serious, but is something that peer reviewers are usually only too happy to point out to you (there is, of course, a fine and fairly hazy line between a truly erroneous conclusion and a disagreement over how particular data should be interpreted). By far the worst breed of wrong, however, is the data error, where some sort of experimental or analytical error invalidates your results, and undermines any conclusions you draw from them. Discovering such an error means that corrections have to be issued, or in the worst cases, entire papers have to be withdrawn. It’s Not A Good Thing.

So you can imagine my horror last Friday, when I was confronted with the serious possibility that a correction error had invalidated all of the palaeomagnetic data I collected for my PhD, and hence the work which represented the bulk of my current publication record.

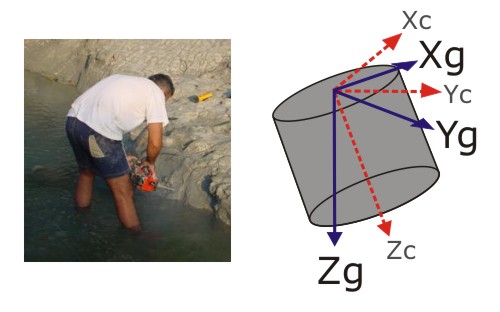

It all started with a puzzling discrepancy. As I’ve discussed before, a number of corrections are required to put directional palaeomagnetic data into the appropriate spatial reference frame. Last week, as I was starting to play around with the preliminary data from my first South African samples, I noticed that the software installed on the lab computer here and the software I’d used during my PhD produced significantly different corrected directions from the same drill core orientations. Both programs work their geometric magic by rotating the sample x, y and z axes to coincide with their original orientations, derived from your measurements in the field.

In both cases I was inputting the z-axis direction – the trend and plunge of the original drill holes – but getting completely different answers. Rather worryingly, this indicated that one of the two programs thought that I was inputting the direction of one of the other sample axes instead. At first I assumed that I was somehow mishandling the new and unfamiliar software, but at the end of last week – after lots of stereonet sketching – I realised that whilst the Jo’burg lab software was correctly rotating the z-axis to align with the measured core orientation, the software that I had used my PhD was rotating the x-axis to align with it instead. This resulted in a direction which was a large angular distance from where it should have been – and I had used exactly the same correction routine for all of the samples I analysed during my PhD. If I was right, this was no simple systematic error, either; not only were all my samples in the wrong reference frame, but each sample was in it’s own wrong reference frame. This would invalidate all my mean directions, all my statistical analyses, everything.

It was at about this point that an entire PhD’s worth of stress hormones decided to dump themselves into my bloodstream. It looked like all the cool and exciting conclusions from my PhD research were built on an exceedingly unsafe foundation. Also, if I was honest with myself, such a glaring mistake galloped far beyond the unfortunate, deep into the realm of the toweringly incompetent. Writing and publishing the necessary corrections and retractions would be equivalent to standing up in a room packed with everyone who might ever hire me and yelling “Hey! I’m a dumbass!”

It was a good job, then, that I turned out to be mistaken – although it took me until Monday to realise it. My salvation lay in the fact that samples were not placed in my old magnetometer in the ‘right’ orientation: what the machine measured as the x-axis was in fact the z-axis of the sample. This substitution meant that when the correction software rotated what it thought was the x-axis, it was actually rotating the z-axis of the sample, which meant that I was supplying the right direction and everything had ended up in the appropriate reference frame. ‘Phew’ is an understatement.

Stressful as it was for me, this whole little escapade brings up some interesting issues regarding the nature of the error-correcting machinery of science. It is often said that individual mistakes don’t particularly matter in the long run, because repeated experiments and testing of conclusions will progressively weed out bad data, mistaken hypotheses, and flawed models. But it has occurred to me that the sort of error that I briefly thought had scuppered my data would be extremely difficult to identify from what is in the public record. The data as presented in a paper are always cleaned up, processed, and corrected; ideally, then, the steps which culminated in the nice clean plots you reveal to the world are also described, so that people can confirm that you’ve treated the data properly. But this is generally a confirmation in principle, rather than taking your raw data and undertaking a time-consuming replication of each processing step. In other words, whereas people might notice if you don’t perform standard procedure x, provided that your numbers don’t look too spectacularly odd they are far less likely to notice if you perform procedure x wrongly.

It’s somewhat sobering to think how much everyone takes on trust that your experimental procedures have been performed correctly and as described. Of course, because it is still exceedingly rare for anyone outside of the author list to have easy access to all the raw data or code from a particular study, people have to trust that is the case. By choosing to place these things away from the scrutiny of the wider scientific community (the pros and cons of which are a whole other argument), the authors have an increased responsibility to audit their own data and procedures, and where mistakes are found, publicise corrections as widely as possible – however personally embarrassing that may be. I’m just glad that in this case, I don’t have to.

Comments (12)