I’ve been reading a few news items today about fossilized black smoker chimneys from China. This rang a few bells, as I wrote about a paper which talked about exactly the same thing on ye olde blog back in January. As it turns out, it’s the same paper, by Jianghai Li and Tim Kusky , which has only just been officially published – it came to my attention via a Sciencedirect e-mail alert when it was in press (accepted but still waiting for formatting and a slot in the next available journal issue). Was that a faux-pas I wonder?

Anyway, as it appears to be topical, I thought I’d repost my thoughts. I have to say that I’m a little suspicious of the ‘key evidence of life’s beginnings’ spin being applied to these findings – the first evidence of life in the geological record comes in beyond the 3.5 billion year mark, meaning that there is more distance between the first replicating organisms and these black smoker microbes as there is between the black smoker microbes and us. As I say below, this discovery could be considered suggestive, but drawing too many sweeping conclusions would be a tad hasty.

From ye olde blog:

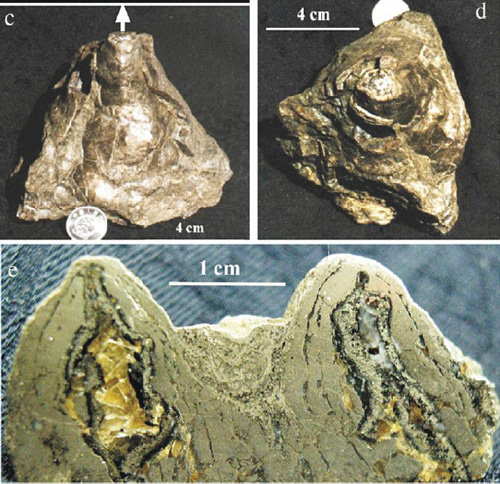

These are pretty cool – some excellently preserved black smoker chimneys from a 1.43 billion year-old massive sulphide body in northern China:

Hydrothermal vents occur at mid-ocean ridges or volcanic hotspots: seawater, permeating down through cracks in the crust, comes into contact with hot rocks above the magma chamber, and reacts with them as they are heated to a couple of hundred degrees C – leaching out metals such as lead, copper, zinc and iron. These hot, buoyant fluids then return to the surface at vent sites, mix with sulphate-rich seawater and rapidly cool, leading to the precipitation of iron sulphides in chimney-like structures. Here’s a more typical view:

Individual vents are generally short-lived, and when the upwelling hot fluids inevitably migrate somewhere else, the fragile spires tend to collapse under their own weight. Massive sulphide bodies – valuable sources of metal ore – are built from the debris of many generations of collapsed smokers in a long-lived vent field. So it’s quite rare to see such well-preserved fragments. I just wish the authors had included some pictures of the things in situ.

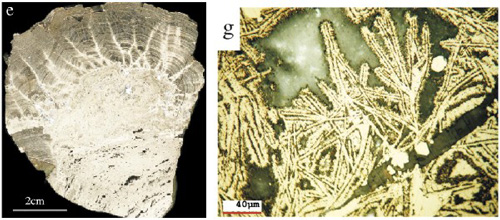

Under the microscope, you can even see evidence of fossilised microbes: on the outside of the chimneys are stromatolite-like ‘microbialites’ – layered deposits of sulphides and organic carbon, sometimes containing mineralised filaments similar in morphology to bacteria found in and around modern vents.

Hydrothermal systems – where interesting chemistry is driven by geothermal energy – is considered to be one place on the early Earth where life could have perhaps arisen; those favouring such a scenario (which includes those hoping for extraterrestrial life in places like Europa) will be happy to see evidence of a flourishing ecology in such environments so long ago.

Source: Li and Kusky (2007), Gondwana Research 12, 84-100 [doi]

Comments (1)