On Saturday night, as many people were enjoying an evening out in Maryland, and I was enjoying an evening in in Ohio, a tweet from Johns Hopkins professor and Baltimore resident, Dr. Sarah Horst caught my eye:

I didn't know it was possible for this much water to fall from the sky all at once

— Sarah Hörst (@PlanetDr) July 31, 2016

She followed up with a video and an offer for people to come whitewater rafting on her driveway. After those tweets, I found a virtual deluge (pardon the pun) of tweets from Baltimore and surrounding residents describing unbelievable rainfall and swiftly rising waters. Soon, reports of people trapped in cars and swiftwater rescues underway began to pour in, from parts of the Jones Falls stream valley in Baltimore and from Ellicott City, 10 miles to Baltimore’s West.

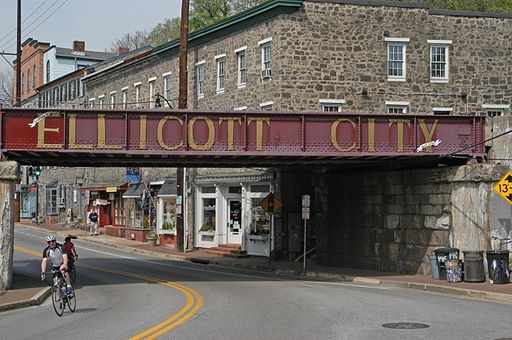

Downtown Ellicott City, in drier times. Photo by Scott Sagihirian used under a Creative Commons license. Sourced from Wikimedia.

Ellicott City is well-known in the Baltimore-Washington area for its historic downtown with a wide selection of shops and restaurants, which would likely have been quite popular on Saturday evening. I remember a fun evening out there a few years after college, when I had a mini-reunion with my roommates.

But this Saturday evening it started to rain. And then it began to rain really really hard. And then the floodwaters began to rise:

WOW H/T Meteorologist Justin Berk and Historic Ellicot City Inc flooding in Ellicott City #Maryland. @capitalweather pic.twitter.com/uqHvlMK6n4

— Marshall Shepherd (@DrShepherd2013) July 31, 2016

By the light of day, the extent of the damage became clear.

Oh man. Just got to walk down Main Street in Ellicott City. One word: Destruction. pic.twitter.com/csaPnHED09

— Kevin Rector (@RectorSun) July 31, 2016

Cars washed away and stacked on top of each other (imbricated in the flow direction). First floors of stores and restaurants covered in mud, with 200 buildings damaged, some probably beyond repair. Sidewalks buckled, ripped away, and collapsed. Harrowing tails of escapes upstairs, up ladders, and uphill. Rescued people via human chains and via emergency responders. Two dead. Washed away in the torrents.

Ellicott City had received 4.5 inches of rain between 7:30 and 8:30 pm and more than 6.5 inches of rain over the course of the evening. Some estimates of the rainfall amounts are even higher, but all show Ellicott City as the bullseye of the downpour:

Quick rainfall analysis resulting in July 30, 2016 #ellicottcity #flashflood. These 3h amts are off the charts! pic.twitter.com/GpsxQKh829

— Greg Carbin (@GCarbin) July 31, 2016

24 hr observed precipitation through 8am this morning pic.twitter.com/c69dI12g8i

— NWS DC/Baltimore (@NWS_BaltWash) July 31, 2016

This amount of rain in such a short time blows our precipitation records out of the water. (Sorry, the puns just write themselves.) No official records are kept in Ellicott City, but based on nearby records, the rain event has a probability of something like 0.1% in any given year. We often call this a 1000-year storm, but just because it happened in 2016 tells us nothing about whether it will happen again in 2017, so probability is a better way of expressing that. Of course, precipitation records are nowhere near long enough to tell us about 0.1% probabilities, so what can really be said is that this rain event was unprecedented in the 100-200 or so years of records we have for the site.

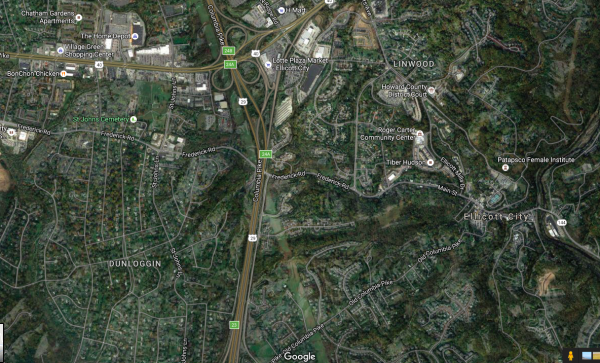

Being caught in a record-breaking deluge is enough to put a damper on a Saturday evening out, but being caught in that sort of rain storm on Main Street of Ellicott City is a disaster. Ellicott City has the hydrologic misfortune of being located where three streams come together in a narrow valley. The combined stream runs right along the back of Main Street businesses, before funneling into the Patapsco River.

I’ll have another post, later, that puts Saturday night’s flooding into the historical context of flooding in Ellicott City and the surrounding area. For now, let’s just say that this is hardly the first time Main Street has seen raging waters pass through the business district. What made Ellicott City a good location for water-based transportation and milling in the 1700s makes a risky location for a town ever since.

As resdients and business owners begin to clean up from yet another flood, they might be asking themselves a few questions: “Does it make sense to rebuild in a place with such a history of flooding?” That’s a question whose answer depends on economic decisions about acceptable losses in the insurance world and personal and societal decisions about acceptable risks.

Residents, business owners, and insurers might also be asking themselves a science question: “Does our changing climate make events like this more likely?” The short answer is, yes, although attributing the increased chances of any single event to climate change is a complicated business. But there is good evidence that extreme precipitation has increased in intensity over the past few decades, and our climate models suggest that intense rain events will continue to get more intense in the future. That’s because a warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapor, making available more water in the sky when it all comes pouring down on a place like Ellicott City. While the details of exactly where and how much precipitation extremes will increase are still an area of debate, some writers are beginning to describe climate change as weaponizing our atmosphere. Maybe that’s a bit hyperbolic, but people trapped in the floodwaters Saturday night might not think so.

There’s one more thing that likely contribute to Saturday night’s disaster and makes matters worse for Ellicott City now and in the future.

Storm drain receiving urban runoff. Photo by Robert Lawton, used under a Creative Commons license from Wikimedia.

So was Saturday night’s flash flood a freak event with a 1-in-a-1000 probability? Was it a symptom of an increasingly extreme climate system? Or was it manufactured by urban land use and inadequate stormwater management upstream? It’s quite possible that it was all three. Further, given the geography of Ellicott City and all of the above factors, a flood like this was an eventual inevitability. It’s just too bad for those who set out to enjoy a night out that it happened to be this particular Saturday night.

Nice plan for content warnings on Mastodon and the Fediverse. Now you need a Mastodon/Fediverse button on this blog.