![]() It wasn’t the biggest seismic event of the week, but this shallow (15 km depth) magnitude 6.0 that shook the remote southeast corner of Kazakstan on Monday still caught my attention.

It wasn’t the biggest seismic event of the week, but this shallow (15 km depth) magnitude 6.0 that shook the remote southeast corner of Kazakstan on Monday still caught my attention.

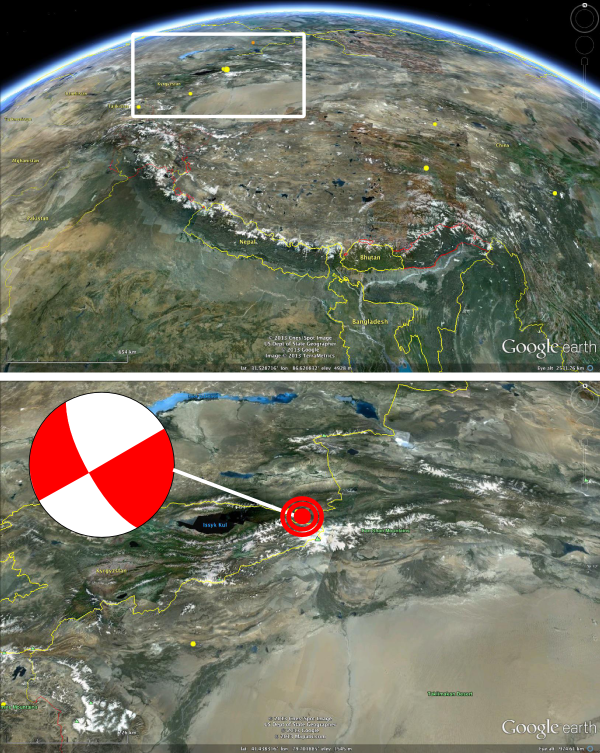

Location and (strike-slip) focal mechanism for Monday’s M6.0 earthquake in the Tian Shan Mountains, SE Kazakstan.

Located within the Tian Shan mountains, this earthquake is testimony to the profound and ongoing regional impact of the collision of India with Asia over the past 50 million years or so. This crash of continents has thrown up the Himalayas, and behind them raised the Tibetan plateau; but GPS measurements of deformation for this region show that even 500 kilometres further inland still, the northward motion of India is still being felt, pushing and squashing the Asian crust, raising the Tian Shan mountains – and causing this earthquake.

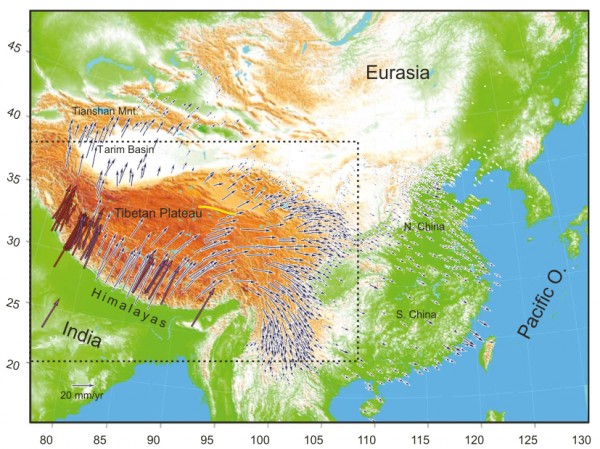

GPS measurements of deformation associated with collision between India and Asia. Motion vectors are relative to the non-deforming interior of Asia. Source: Gan et al., 2007.

This is a good example of how unlike plate tectonics in the strict sense the deformation of continental crust can be: rather than large, rigid chunks of crust which interact only at their edges, the ‘plate boundary’ between India and Asia stretches a long way into Asia. Rather than a single fault system, you have an entire region gradually absorbing India’s inward charge. But this event is interesting for another reason: the reported focal mechanism suggests that the rupture was due to strike-slip motion on a fault, either dextral strike slip on an northwest oriented fault (north-east side moving south-east) or sinistral strike-slip on a southwest oriented fault (northwest side moving southwest).

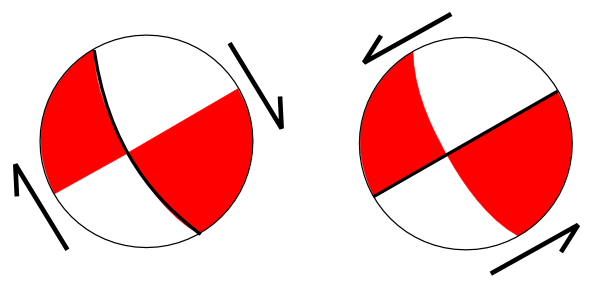

The two possible interpretations of the focal mechanism. Dextral strike slip on NW-SE fault, or sinistral strike-slip on a SW-NE fault.

Strike-slip is perhaps a bit of a surprise, since most earthquakes in this region seem to be on thrust faults accommodating north-south compression. These faults mostly appear to be following a northeast-southwest trend, which might suggest that we are seeing sinistral strike-slip on one these structures, as in the first possibility above. However, this implies some sort of lateral escape tectonics in this area, where rather than being all squashed and crumpled up to make room for India’s incursion, some of the Asian crust simply moves out of its way. This is clearly evident in eastward GPS vectors seen in eastern Tibet, but is not particularly compatible with the SW-NE trend of the GPS-derived motion in the Tian Shan. However, it turns out that about 200 km to the west, on the other side of Lake Issyk Kul, there is an 800 km-long, active, northwest-southeast trending dextral strike-slip fault, the Talas-Fergana Fault (TFF):

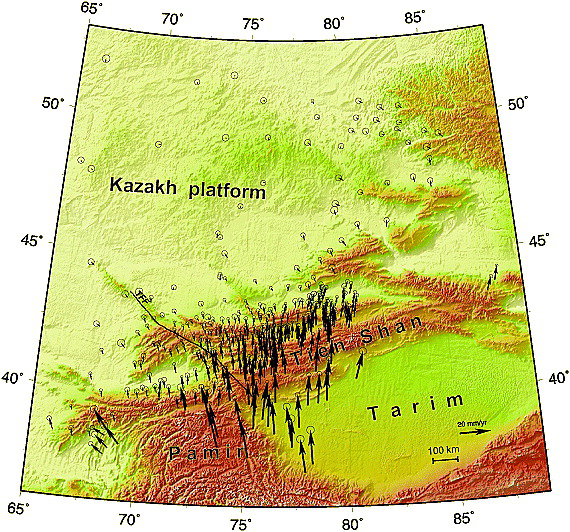

GPS velocity field for Tian Shan; motion vectors relative to stable Eurasia. TFF=Talas-Fergana Fault. Source: Zubovich et al., 2010.

Monday’s earthquake could therefore have occurred on a smaller but similarly oriented structure east of the Talas-Fergana fault (meaning that the first of the two possibilities suggested above is correct). Over 1000 km beyond the main collision front, the northern motion of India is causing deformation; and in the Tian Shan that deformation is being accommodated by N-S strike-slip faults as well as E-W thrust faults. Why is it doing it that way? I suspect it may have something to do with us being near the eastern edge of the Tarim Basin, which is thought to be a strong, rigid block that is not deforming very much. Based on the GPS velocities in the figure above, the Tarim block appears to transmit the stress from the Himalayas and Tibet further northwards into the Tian Shan than is possible in the weaker crust beyond its edges. Strike slip faults such as the Talas-Fergana fault, and possibly the fault that ruptured on Monday, are accommodating the difference. That’s continental tectonics for you: why use one fault when you can use whole different sets of faults at the same time?

Note:No promises, but I’m hoping to make this a quasi-regular feature again.

Comments (2)