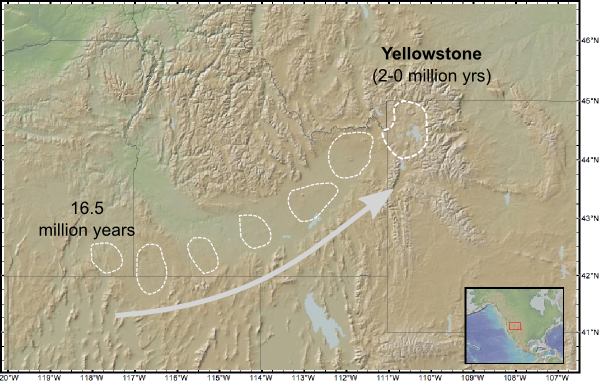

![]() A couple of weeks ago, I showed the trough excavated through the mountains of the western US by explosive caldera eruptions above the migrating Yellowstone hotspot.

A couple of weeks ago, I showed the trough excavated through the mountains of the western US by explosive caldera eruptions above the migrating Yellowstone hotspot.

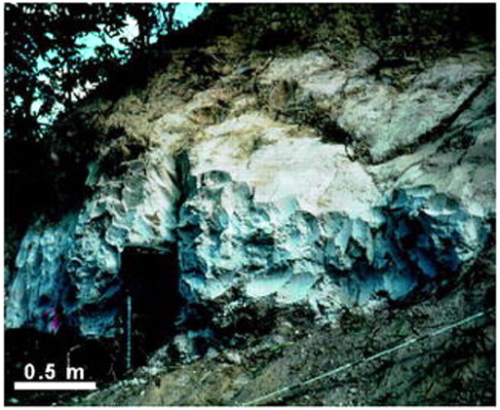

These eruptions excavated a lot of rock: the most recent eruption of the Yellowstone caldera, 600,000 years ago, pulverised 1000 cubic kilometres of crust into ash and threw it into the atmosphere. When it finally settled to the ground again, a lot of it had drifted or been blown hundreds of miles away from Yellowstone. It settled in Kansas.

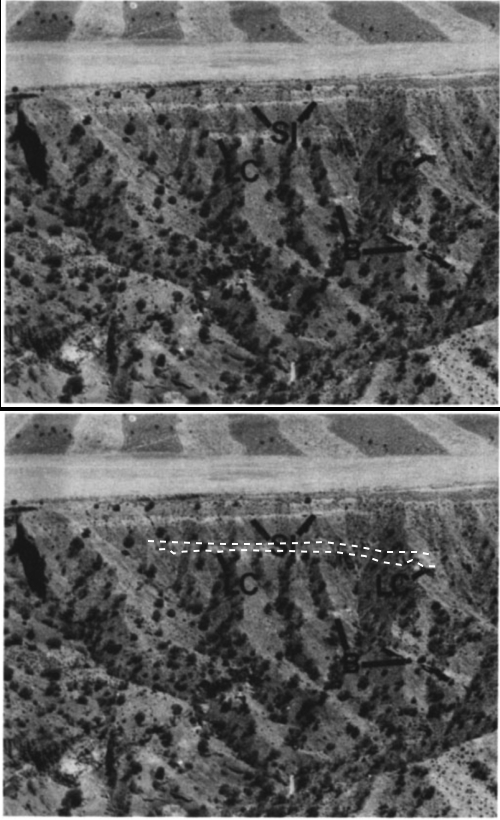

It also settled in Utah (apologies for the rather distant and grainy photo).

And some floated as far as Western Iowa.

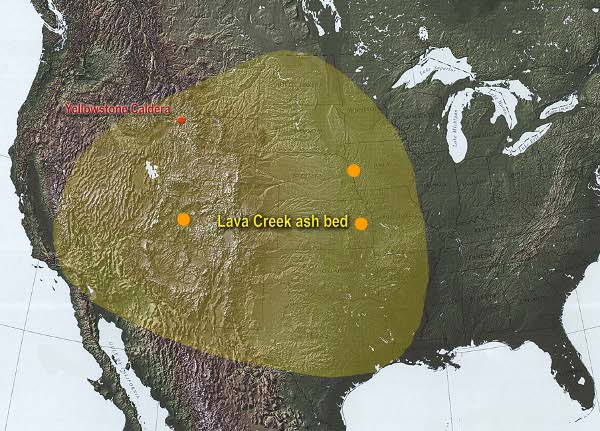

In fact, 0.6 million year-old ash layers, with a distinctive mineral composition that links them to the same eruptive event and to the Yellowstone caldera, can be found in sequences over a sizeable proportion of the continental US. Collectively, this unit is known as the Lava Creek Tuff (sometimes referred to as the Pearlette ash in older literature).

Distribution of Lava Creek Tuff in continental United States. Orange dots - ash layer outcrops pictured above.

This is another way that the almost unimaginable scale of a large caldera eruption compared to the kind of volcanic activity we have direct experience with can be highlighted. The ash from the Eyjafjallajokull eruption earlier this summer was dispersed more than 1000 km from Iceland by strong winds, totally disrupting air travel as it went; but the ash that settled on the ground in Western Europe was, at most, a light dusting – it would be generous to say half a millimeter. As the outcrops above demonstrate, an equivalent distance (1000 kilometres) from Yellowstone, the Ash Creek tuff is about half a meter thick – one thousand times thicker. Three orders of magnitude. Somewhat eye-opening, don’t you think?

On the plus side, the Lava Creek tuff, and similar widely distributed ash layers from earlier eruptions of the Yellowstone caldera chain since 16 million years ago, provide a set of useful correlative markers between sequences in widely seperated sedimentary basins in the US – igneous index fossils, if you will.

Comments (11)