![]() During our little climatic digression in this week’s podclast, Chris brought up a study that I hadn’t heard about, in which Paul Newman (no, not that one) of NASA’s Goddard Centre (who have a nice write-up) and his colleagues play a game of climatic what if: what if the discovery that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) destroyed stratospheric ozone had been ignored, and were not phased out in the decade following the signing of the Montreal Protocol in 1987? Do our more sophisticated climate models, which can more accurately simulate atmospheric chemistry and wind patterns, confirm the hypothesis that if we had continued to emit CFCs and other ozone destroying chemicals, the ozone layer would have been severely damaged?

During our little climatic digression in this week’s podclast, Chris brought up a study that I hadn’t heard about, in which Paul Newman (no, not that one) of NASA’s Goddard Centre (who have a nice write-up) and his colleagues play a game of climatic what if: what if the discovery that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) destroyed stratospheric ozone had been ignored, and were not phased out in the decade following the signing of the Montreal Protocol in 1987? Do our more sophisticated climate models, which can more accurately simulate atmospheric chemistry and wind patterns, confirm the hypothesis that if we had continued to emit CFCs and other ozone destroying chemicals, the ozone layer would have been severely damaged?

To answer this question, Newman et al. ran two scenarios in the same climate model, and charted the evolution of stratospheric ozone in each. The first model was based on the current (low) emissions of ozone-destroying chemicals resulting from the implementation of the Montreal Protocol; in the second, rather poetically named “world avoided” model, CFC emissions increase by 3% a year (“business as usual”) after 1974, when the ozone alarm was first sounded (and was presumably ignored in this parallel universe).

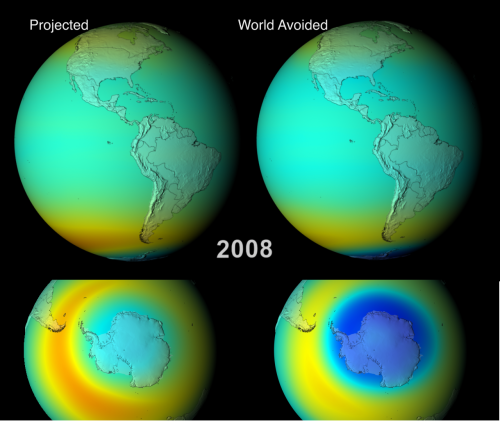

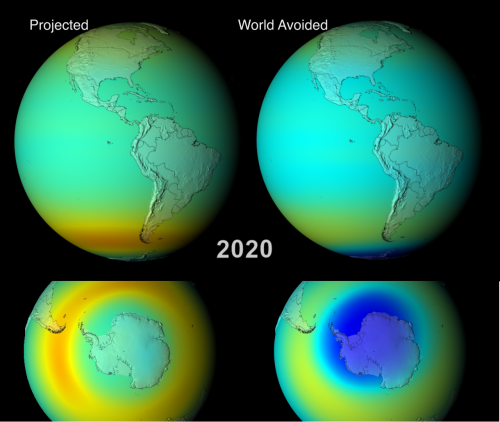

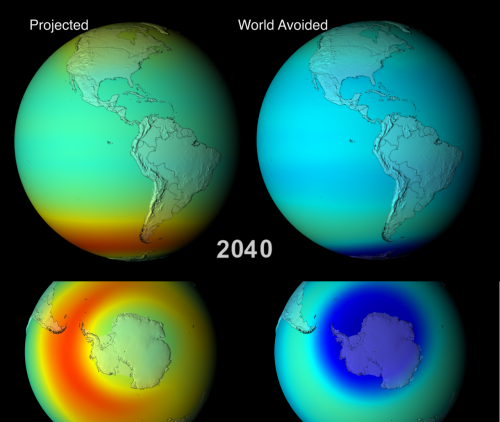

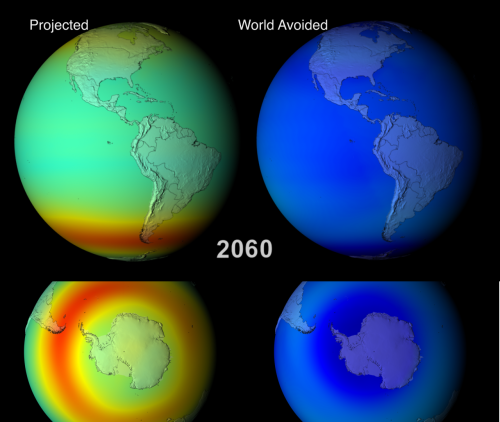

Animations fully depicting the results of both scenarios between 1974 and 2065, are available, and are well worth a watch. Below I show some edited highlights: side-by-side comparisons of the two models during September/October (southern hemisphere spring, when the Antarctic ozone hole reaches it’s maximum extent) in 2008, 2020, 2040 and 2060.

The snapshot from last year already shows a clear divergence between the two models; the ozone hole in our reality is still prominent (once you account for the difference in scale, it matches quite well with the actual one), but far more ozone seems to be being destroyed in the world we avoided. The models therefore suggest that even though the ozone hole hasn’t fully healed, cutting back on CFC emissions has clearly limited the extent of the damage.

This difference in the south polar region becomes more pronounced through 2020 and 2040; the animations also show that by 2040, the Antarctic of the “world avoided” has an ozone hole for all or most of the year, rather than just for a couple of months. Even more ominously for the residents of this alternative world, the much bluer colours at lower latitudes indicate that ozone depletion is also occurring outside the polar regions. In fact, by 2040 the average atmospheric concentration of ozone is below the 220 Dobson Units (DU – see the scale below the 2008 figure) which is used to characterise the modern ozone hole. So in a certain sense, there is no ‘hole’ anymore – it’s gone global.

And if that looks scary, by 2060 there’s virtually no stratospheric ozone anywhere. It’s gone, and with it our protection against ultraviolet radiation. The authors put it in pretty stark terms:

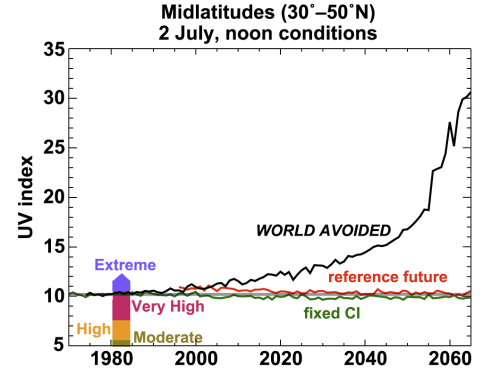

DNA damaging UV for the [Northern Hemisphere] midlatitudes increases by approximately 550% between 1980 and 2065.

It should be noted that these models only looked in detail at the upper atmosphere, and did not model the interaction between the atmosphere and oceans; sea surface temperature data from runs of properly coupled climate models was used as a boundary condition instead. The effects of the excess CFCs, which are themselves potent greenhouse gases, on sea surface temperatures is therefore not included in the “world avoided” model; and the chemical effects of greater ultraviolet penetration into the lower atmosphere are also unconstrained. Despite these uncertainities, however, it seem pretty clear that we got our environmental act together just about in time to dodge a rather carcinogenic bullet.

P. A. Newman, L. D. Oman, A. R. Douglass, E. L. Fleming, S. M. Frith, M. M. Hurwitz, S. R. Kawa, H. Jackman, N. A. Krotkov, E. R. Nash, J. E. Nielsen, S. Pawson, R. S. Stolarski, & G. J. M. Velders (2009). What would have happened to the ozone layer if chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) had not been regulated? Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 9, 2113-2128. (open access)

Comments (44)