Old geological theories don’t die, they’re just passed on to cranks – as the Expanding Earth Theory demonstrates. For those who have missed the recurring infestation of Expanding Earthers in the geoblogosphere (Eric, Bryan, Brian and most recently Julia have all been afflicted), and before I explain how the facts of the geological record conclusively falsify their model, I should acknowledge that it does actually incorporate a couple of valid ideas: that you can fit all the bits of continental crust on the Earth’s surface, which are nowadays separated by sizeable ocean basins, back together into one coherent landmass; and that the ocean basins represent a different kind of later-forming crust that has formed between them and pushed them apart.

Indeed, back in the early 1900s, as a way of explaining the puzzling morphological and geological connections between the opposite sides of the Atlantic, the notion that the ocean basins had formed in the gaps left as the Earth increased its radius over time was arguably a more plausible explanation for “continental drift” than Alfred Wegener’s conception of continents moving through the oceanic basins – or, at least, the physically implausible part was moved into the centre of the Earth, where it was less immediately obvious. To advocates of the Expanding Earth, then, the discovery of sea-floor spreading in the late 1950s and early 1960s probably looked like an exciting confirmation of their hypothesis- until geologists ruined the whole thing by showing that ocean trenches are subduction zones, where crust is recycled back into the mantle*. The creation of new crust at spreading ridges is therefore balanced out by its destruction at trenches, removing any need for the Earth to have got bigger – or break several fundamental laws of physics.

Suffice to say, the few remaining Expanding Earthers really, really don’t like subduction, and spend most of their time trying to “prove” that it don’t exist. In doing so, they conveniently ignore the fact that one of the basic predictions of the expanding earth model – that oceanic crust is only created, and never destroyed – is clearly contradicted by clear geological evidence for the presence, and closure, of older ocean basins.

One of the original strands of evidence that Alfred Wegener used to infer the prior existence of the supercontinent Pangaea was that plant and animal fossils from rocks of Late Paleozoic and Early Mesozoic age (approximately 200-400 million years ago) from now widely distributed continents were all remarkably similar. This shared biological history implies a geographical link that was lost following the opening of the Atlantic, leading to the extinction and evolution of different species on either side of the oceanic divide.

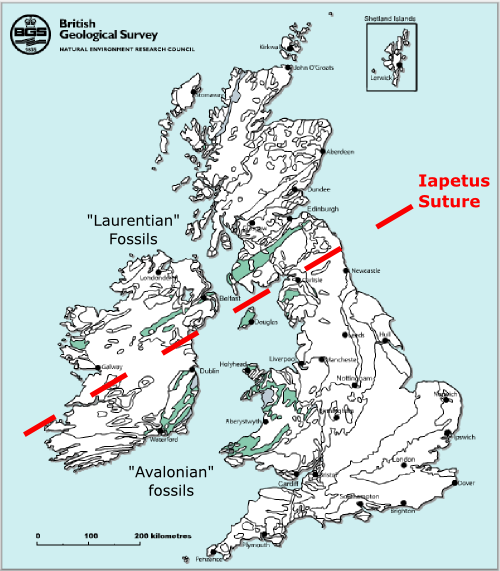

Having established the principle that similar plants and animals imply a geographical connection, and different plants and animals imply geographical separation, if you look at British rocks older than the ones used by Wegner and others to establish the Pangaea connection, you discover something rather interesting. The map below, courtesy of the BGS’s nifty Make-A-Map application, shows the distribution of Cambrian (grey) and Ordovician (green) rocks, 550 to 450 million years old, in Britain and Ireland.

The fossils can be clearly divided into two distinctive groups, or assemblages: the trilobites, brachiopods, and other shallow marine animals to the south of the red dotted line (the reason for it being labelled the “Iapetus Suture” will be revealed below) are completely different from those found to the north of it.

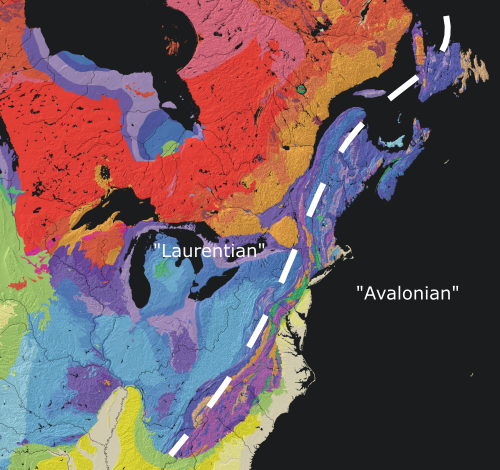

It gets even more interesting when you look over the other side of the Atlantic. The USGS don’t seem to have an on-line map-making app, they do have the rather beautiful “Time and Terrain” map, of which the image below is an excerpt. Cambrian and Ordovician rocks are purple.

Not only can you make a subdivision between two distinctive fossil assemblages, but it’s the same subdivision – the rocks on the coast, east of the white dotted line, contain the same fossil groups as rocks of the same age in the southern British Isles – which is usually referred to as the “Avalonian” assemblage, after the Avalon Peninsula in Newfoundland. Palaeozoic rocks in the continental interior contain an entirely different, “Laurentian” assemblage, which consists of exactly the same fossil groups as are found in Palaeozoic rocks in Scotland.

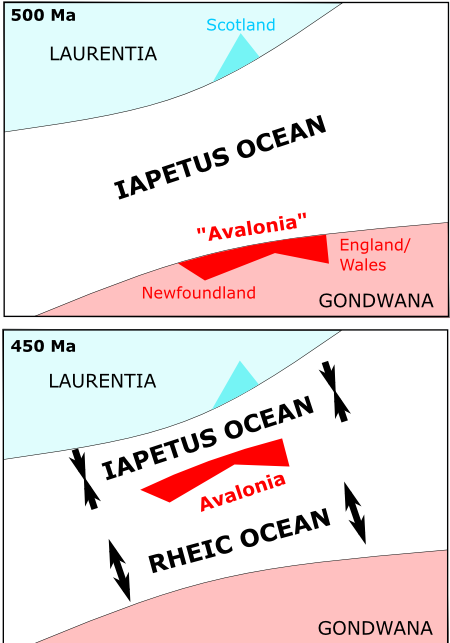

It gets better. In the Cambrian and early Ordovician, the “Avalonian” fossil assemblage is closely linked to fossil groups found in similarly aged rocks in north-west Africa (now exposed in places like the Atlas Mountains in Morocco). Then, in the mid-late Ordovician (from around 460 million years ago), that link is broken, and Avalonian species form a unique assemblage that is only found in rocks from Newfoundland, Wales and the Lake District (and possibly some places in Belgium and Germany) – they are distinct from Africa and North American groups. Finally, in younger rocks, the fossil assemblages in all of these places start looking quite similar.

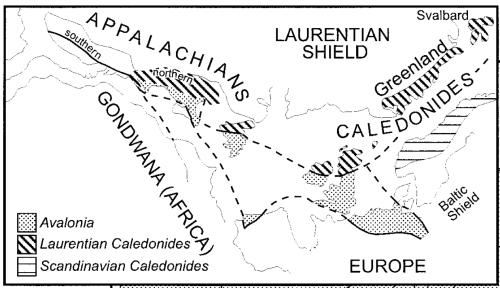

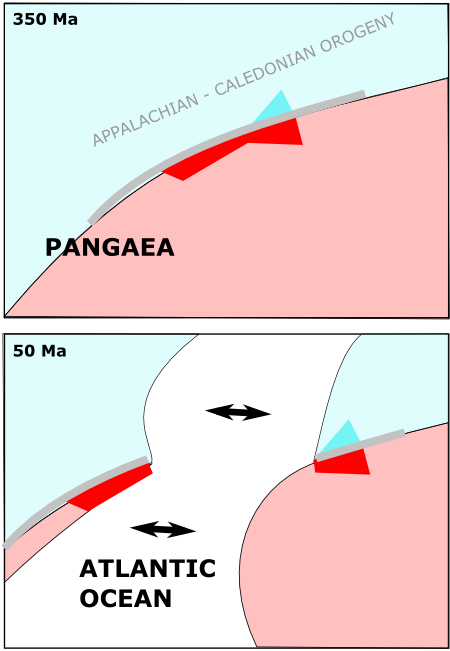

So what’s going on? Well, reconstructions of Pangaea show that when you close up the Atlantic, Newfoundland and bits of Britain that contain the Avalonian fossils are juxtaposed against each other, and located on the same side of a particular geological feature – the Appalachian-Caledonian mountain belt (figure from McKerrow et al., 2000, J. Geol Soc. Lon. 157, 1149-1154).

Laurentian fossils are located on the far side of this mountain range, so it does seem to be related; however, it is a younger feature than the rocks it rises up between, having started forming about 350 million years ago. It can’t have acted as a physical barrier preventing the mingling of Ordovician lifeforms, because it wasn’t actually there yet.

The first to realise what the Avalonian rocks were telling us was J.Tuzo Wilson – possibly the smartest of the very smart bunch of people who formulated plate tectonics. He reasoned that observing distinct and unrelated forms of life in two different regions means exactly what it would mean in the present day – that those regions were geologically isolated from each other. Even if Scotland and Southern England are now right next door to each other, during the Cambrian and Ordovician, the “Avalonian” and “Laurentian” rocks were deposited on the opposite shores of a long-vanished ocean. Scotland and North America formed one coastline of the “Iapetus Ocean”, and Africa, Newfoundland, and Southern Britain formed the other. The width of this ocean was sufficient to prevent the distinctive marine species inhabiting each of these shores from mixing. By the same reasoning, the bifurcation of Avalonian species from North African ones around 450 million years ago is a sign that a block of crust consisting of Newfoundland and southern Britain had rifted away from the larger African landmass, forming a distinct and isolated microcontinent which for obvious reasons is usually called Avalonia.

Eventually all of these fragments came together to form Pangaea, with the Appalachian and Caledonian mountains being formed by the continental collision that marked the final closure of the Iapetus and Rheic oceans (marked by the Iapetus Suture on the UK geology map above). Finally, a hundred million years or so later, something triggered another continental break-up. The rifting that went on to form the Atlantic ocean occurred along a similar trend to the Iapetus Suture, possibly because it was a zone of pre-existing weakness, but it wasn’t exact – some bits of the Laurentian shoreline got stranded on the wrong side, and vice versa.

This inexact breakage provides the clues necessary for Wilson’s great insight – that the geological record doesn’t just show Pangaea breaking up into smaller fragments, it shows that Pangaea was itself amalagamated from smaller, pre-existing continental fragments – by the closure of ocean basins. By subduction, or at least a process that is destroying oceanic crust. This has no place on an expanding earth. It is falsified. It is an ex theory. It is pushing up the paradigms.

The geological record goes further; the picture is a little more fuzzy the further back in time you look, but the fragments that came together to form Pangaea seem to have themselves been the scattered remnants of an even earlier supercontinent (mostly referred to as Rodinia), which was itself welded together from older fragments. Earth’s geological history seems to have consisted of several cycles of supercontinent formation and break-up – also known as Wilson Cycles, in honour of the man who solved the Avalonian conundrum by proposing them.

Of course, Expanding Earthers and their intellectual kissing cousins, the Catastrophic Plate Tectonics crowd, completely ignore the evidence that clearly falsifies their pet “theories”, which cannot explain the sequential opening and closing of ocean basins. But they are falsified nonetheless. And that, Virginia, is why we refer to them as cranks.

*although in reality, the first evidence for subduction zones dates from the 1930s.

Comments (10)