The afternoon of my second day at AAPG was spent at the session debating the origins of the Lusi mud volcano, which has been the subject of a number of blog posts around these parts. The selling point was that this would be the first time that the major proponents for the theory that the eruption was caused by a blow-out in the gas well being drilled nearby, and the competing theory that it was a response to a large regional earthquake that occurred two days before the eruption, had been collected in the same room to argue things out. Whilst this wasn’t entirely true – there was a similar debate in London last week – I was quite happy to catch the rematch.

Things were a bit different from the other sessions at this conference: photographers and cameramen were roaming the room, and on my way in I had a press release from Lapindo Brantas thrust into my hands, informing me that most of the previously reported findings were based on ‘incorrect data’, and that this would be the first time ‘official data’ were presented to the scientific community. It transpired that this was also stretching the truth a bit; as the session unfolded it became apparent that this was more an issue of which data (specifically, which of the various measurements and estimates of borehole pressure) should be used, and how to interpret them. Contrary to their own press office, then, Lapindo Brantas – to their credit – seem to have been quite open about sharing their records with any interested party, even if they might disagree with how it is then used.

The debate consisted of two talks from the pro-earthquake camp, followed by questions, then two talks from the pro-drilling camp, followed by more questions and a general discussion, ending with a poll of the audience. Below I’m summarising from notes I took during the session; as such, there may be some unintentional inaccuracies.

First up was Adriano Mazzini, who reviewed his arguments that the eruption was the result of the Yogyakarta earthquake reactivating a pre-existing fault that runs through the area. Main points:

- There is clear evidence of displacement along this fault after the eruption, and other small mud eruptions also occurred along its trace at the time Lusi erupted. This does indeed signal that this fault acted as a conduit for upwelling fluids.

- However, the question of what triggered this trigger – the ultimate cause of the fault suddenly becoming an open pathway for mud – is still open. The timing of the fault reactivation is not known, so it could just as easily have been the result of stresses induced by a nearby well blow-out as by an earthquake. In support of the latter, pressure losses in well at the time of the earthquake might indicate that there were measurable stresses being induced in the subsurface, more than is assumed by the pro-drilling camp.

- Lusi’s eruption has been abnormally lengthy; natural mud volcano eruptions tend to last a few days (and in this respect it seems that Lusi also differs from the other eruptions in the area he talked about, which were further from the borehole). It might be something to do with this being an entirely new system, but it could just as easily be a sign of unnatural influences on the triggering of the eruption.

- This area of Indonesia is “ideal”, both in terms of prevailing tectonic, structural and lithological conditions, for the formation of mud volcanoes, and the existence of a highly suitable ‘piercement structure’ (the fault) in the area meant that an eruption was only a matter of time. This last point would become important in the later discussion.

The next speaker, from Lapindo Brantas, was the person who oversaw the borehole, which mades his slightly defensive tone entirely understandable. The talk aimed to use data from the borehole to demonstrate that a blow-out had not occurred.

- The most important claim was that there was no evidence of the well being connected to Lusi’s plumbing, which you would expect if a well blow-out was the trigger. For example, following the eruption of Lusi they performed an “injection test”, where drilling mud was pumped into the borehole. As they did this, the pressure in the well slowly built up, which can only happen if the well is sealed; if there was a breach in the well, the fluid would escape.

- The pressure losses at around the time of the earthquake talk prompted the decision to case the unsealed part of the borehole before drilling deeper. As they were puling out the drill string to do so on the 28th May, there was a ‘kick’ in the hole – an increase in pressure due to fluid entering from the surrounding rock. The pressure increase from this kick, and whether it was enough to trigger a blow-out, is one of the major sticking points of this whole argument.

- The pro-drilling people have published calculations that indicated that it was more than high enough to trigger a blow-out. It was claimed here that these calculations were performed incorrectly, and should give much lower (and safe) pressures. I can’t claim enough expertise to tell if these criticisms were valid or not.

- Either way, borehole records after the kick are inconsistent with it being the result of a well blow-out.

The first speaker from the pro-drilling camp, Mark Tingay, gave a very nice presentation which actually addressed the pros and cons of both theories, although he was clear which he favoured.

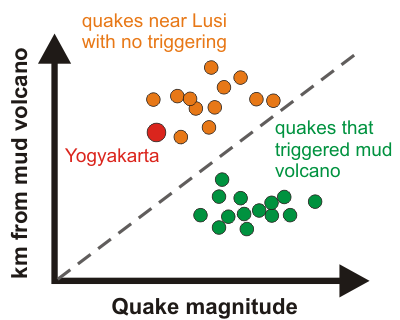

- Earthquake reactivation of the fault seems unlikely from the calculated differential shear stresses it induced in the area around Lusi (for more details you can read Maria’s post on this, since she was involved in this study). He had a nice plot to illustrate this point, which I reproduce schematically here.

Basically, the earthquakes which are known to have triggered mud volcanism (green dots) were either larger and/or closer to the induced eruptions than Lusi was to the Yogyakarta earthquake (big red dot), and other seismicity in the area prior to the eruption (orange dots) appears to have induced similar, or in some cases greater, differential stresses. There is of course a lot of uncertainty about how strong the fault was (how large a differential stress you need to cause it to fail), but the point is that there was nothing special about the May 27th earthquake in terms of the force it exerted in the area.

- The apparent disconnection of the well from Lusi could be due to the lower part being sealed off due to it being blocked by rock fragments from the blow-out (which is apparently quite common), or shearing.

- The evidence following the kick is “unclear”, but the stresses that it induced were an order of magnitude larger than those due to the earthquake

- This was a problematic hole, with lots of pressure losses and kicks, and the ‘drilling window’ – the range of pressures where the drilling mud will safely just sit there – was very narrow. This was a result of the well design being based on holes drilled through this sequence quite a distance away, where the underlying carbonates were not overpressured. However, in another well very close by, the carbonates were under extremely high pressure, and they almost lost that well to a blow-out when they hit them. By not taking this into account, it would have been nearly impossible to stop a blow-out following the kick.

- There is a series of linear surface fractures leading between the well and the Lusi vent, which have not erupted any mud but are an indication of sub-surface fracturing.

The final presentation was by Richard Davies, the person whose paper implicating the drilling kicked off my interest in this subject.

- This talk was a review of the events in the well leading up to the Lusi eruption. It was a very good summary, but most of the points have been covered in my accounts of the previous speakers.

- However, in the middle of the talk, proving that for every expert there is an equal and opposite expert, another (non Lapindo Brantas) drilling engineer came up to the stage to show us how all the well pressure data was consistent with the initial kick being due to a blow-out (I think that the main argument was that you had pressure losses after the hole was sealed).

The discussion following the talks emphasised a couple of other points of disagreement, such as the shaking intensity in the Lusi region from the May 27th earthquake: the pro-drillers say I-II, pro-quakers claim IV. Mazzini also argues that the eruption is entirely sourced within the mudstones with the water produced by clay minerals reacting to form illite and water, whereas Davies et al. say that the water is mainly from the underlying carbonates. It is a lot of water, although I guess it would be hard to claim the earthquake would cause the carbonates to breach.

However, more interesting was that several people picked up on the suggestion that this was clearly a prime area for mud volcano formation, and wondered quite loudly why the hell any drilling was being done there in the first place. To sum up the mood, one questioner complimented the second speaker for standing up there to defend the drilling, when it really should be the geologists who told him to drill there in the first place. It’s a good point; perhaps the focus should be less on the drilling practice on this specific well, because whatever your procedures and safety precautions, accidents can and do happen, and more on well siting decisions in general, particularly decisions to drill in “primed” areas like this one, where the margin for error is rather slim.

This attitude might explain why in the closing straw poll, more than 50% of the audience was willing to blame the whole mess on the drilling. Only a tiny fraction thought that the earthquake was solely to blame, with roughly equal numbers of the remaining half either thinking it could have been both, or finding it inconclusive either way. In conclusion, it was a very interesting session, and was conducted in a very fair-minded and respectful manner given the contentious nature of the debate.

Categories: academic life, conferences, earthquakes, geohazards, Lusi, public science, volcanoes

Comments (8)