Yesterday was the first anniversary of the 2011 eruption of Grímsvötn. Despite being the largest eruption in Iceland in 50 years, the day passed without much fanfare as the eruption had a relatively small impact compared to a certain other eruption the year before. To understand why, read my post from the second anniversary of that one: An Icelandic eruption 100x more powerful than Eyjafjallajökull.

In this post, I want to point out the interesting effects that wind patterns had on the tephra dispersal from the Grímsvötn eruption, and to update you on the analysis of the samples.

Where to go: Greenland or Great Britain?

The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have a webpage where you can have a go at running their HYSPLIT atmospheric dispersion model. This uses information on wind speeds and directions to predict where particles in the atmosphere will travel. It works in forward or in reverse, so if you smell a bad smell, you can find where it came from and if you make a bad smell, you can see where it is going to go. Except on a global scale.

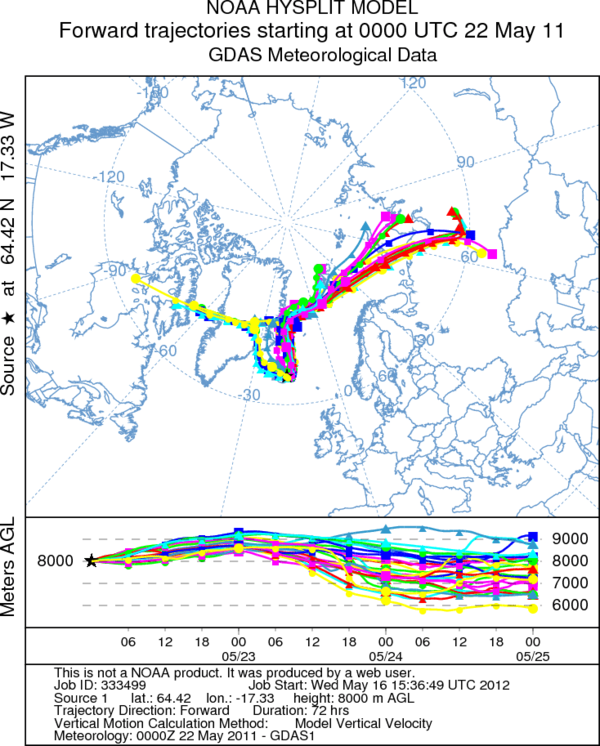

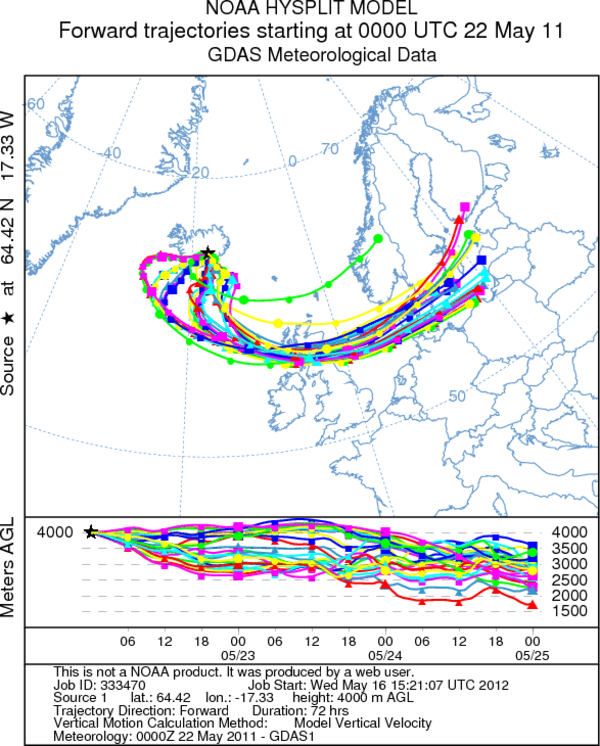

The Grímsvötn 2011 eruption was interesting, because the final destination of the erupted material was controlled really strongly by the height that it reached in the plume. Check out these two plots for comparison:

Material from 8ooo m goes north

HYSPLIT trajectory for particles released at 8000 m. These do not include particle settling, but give a good idea of wind direction. Material is carried north across Iceland, then across to Greenland.

Material from 4000 m goes south

HYSPLIT trajectory for particles released at 4000 m. These do not include particle settling, but give a good idea of wind direction. Material is carried south across Iceland, then across to Great Britain.

Where did the tephra go?

The plume from Grímsvötn reached 20 km in altitude, but it turns out that not all of this was tephra. Much of it was steam and volcanic gas. To see whether most of the tephra was in the upper or lower part of the plume, have a look at this photograph of the area south of the crater, taken on an monster-truck expedition to the crater last August.

A black sandy desert. This is the tephra deposit from Grímsvötn 2011 on top of the Vatnajökull glacier. All this should be white ice and snow. Click the image to read my post about a trip to the crater last summer.

It is clear from the deposits on the ground that most of the tephra from the eruption was carried to the south by low-level winds and was deposited from the lower part of the plume. There was very little tephra deposited to the north of the crater, but material from the upper plume was carried carried to the north and was detected over Greenland by satellites sensitive to the volcanic gas sulphur dioxide (SO2).

This complicated dispersal of volcanic material is another reason why mapping volcanic ash clouds is HARD. The main lessons that were learned are:

- Tephra may not be distributed evenly throughout the full height of an eruption column during a subglacial eruption.

- It is important to get information from the ground and from satellites as quickly as possible to refine computer predictions made during an eruption.

What happened to the samples?

Some of you may remember that during the Grímsvötn eruption, there was a request from the British Geological Survey for samples of ash collected by the public. I made a video and wrote a post at the time called An easy way to sample falling ash, and another post showing some of the ash that fell in the UK. In the end, we received ~130 tape samples from the public and found ash in many of them, particularly ones from Scotland (which is in nice agreement with the particle trajectories above). The results are being written up, but it will still take months for them to be published formally. Such is the pace of science.

Thanks again to everyone that sent samples in.

That there have been huge deposits of volcanic ash by this eruption is something that the people of southern Iceland get reminded regulary. Every time when it was dry for at least a week and then a storm passes of Iceland, this ash is remobelized into the air. Even in Reykjavik, which is about 400km away, this is visible. Last week we had an air polution of almost 300 micrograms ash per cubicmeter air. Town which are closer to Grimsvötn got hit even worse.

Wow! 300 micrograms per cubic metre in Reykjavík is nasty.

I crossed Skeiðurarsandur in April and the ash was bad there. I would recommend taking ski goggles and a mask to anyone that plans to spend time there this summer.

I’m not sure where you’re getting your information, but good topic. I needs to spend some time learning more or understanding more. Thanks for wonderful information I was looking for this information for my mission.