England’s Peak District is made almost entirely from Carboniferous sediments, in a broad anticline. On the outside edges, mid to late Carboniferous rocks are dominated by sandstone, with subsidiary mudstone and coal. The core is an area known as the White Peak where lower Carboniferous limestones form a gentle landscape. It’s a working landscape though, with a long history of mining and quarrying, as we shall see.

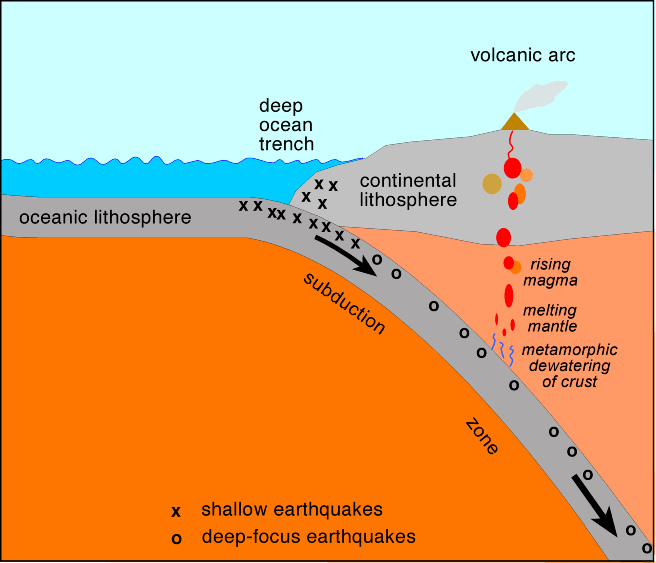

While the limestone was being deposited, most of Derbyshire was a shallow shelf area. The crust was being gently pulled apart and fractured, so the shelf area was surrounded by deeper basins.

Just like the Bahamas

These seas were at tropical latitudes and, on the shelf, relatively free of terrestrial sediment. These are perfect conditions for making limestone, as numerous organisms create calcium carbonate structures that build up into rock.

The typical fossil assemblage you find in these rocks includes rudose corals, brachiopods and crinoids (ancient sea-lilies). Fossil reefs abound, made of limestones packed with (in fact made entirely from) ancient life..

Reef limestones are typically ‘massive’ which in a geological context means lacking obvious bedding planes or other structures. The above photo shows a cave, another distinctive feature of limestone areas. This particular cave has been linked to a ‘green chapel’ that features in a famous medieval story.

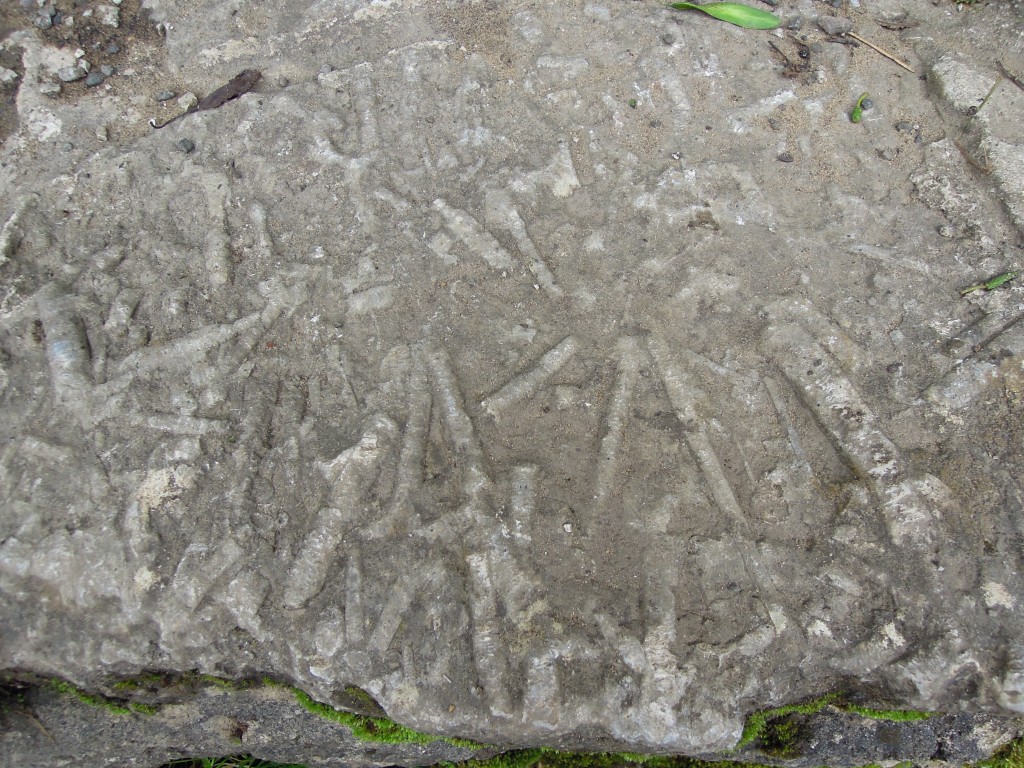

A closer look at the fossils. The round discs is a crinoid ossicle, plates of calcium carbonate that joined up to make the stems. The rock is made up almost entirely of bits of life, either plants or mostly animals, hence the technical term ‘bioclastic’. The numerous little pin-shaped pieces in this sample are (as best as I can tell) brachiopod spines (if you know better, speak up!).

Here’s a worn slab of reef limestone, showing abundant crinoid stems, still in one piece.

These pictures were taken on a recent trip to Derbyshire, where I didn’t spot a decent brachiopod. Conveniently just the other day I spotted one in the gravel of my drive. There are many massive quarries in the Derbyshire limestones and some of it ends up in as builder’s gravel.

Copper-bottomed

There is a long history of mining in the Peak District. There are many ore bodies, typically found in veins associated with faulting. Blue John, an beautiful banded form of fluorite was mined for ornamental purposes. Less glamorously, lead, zinc and copper have been mined since Roman times. The mineralisation was deposited by hot fluids that formed as the sediments became buried.

Around Ecton the mining was mainly for Copper. Ecton Copper Mines, were most active from early C17th until 1891. Peak production was 4000 tons in 1786. A major use of copper at this time was covering the bottom on ships in the Royal Navy. Sheets of copper (or zinc copper alloy) were used to protect the wooden ships from the attentions of marine life, particularly Teredo worms (‘shipworm’). The Navy’s ships were cutting edge technology at the time, projecting British power across the globe. They were sometimes used for scientific work too, for example His Majesty’s Ship Beagle that carried Darwin on his famous voyage.

Traces of the mining remain. Found at the bottom of Ecton Hill this is mostly like a sough (pronounced “suff”) a channel to drain the mine shafts higher in the hill.

Ecton also contains this odd rock.

This is calcrete, an angular limestone cemented by groundwater CaCO3 during the Pleistocene. Basically its old scree that got stuck together.

There’s quite a lot of it.

Deep waters

The Ecton limestone is a thinly bedded limestone, with minor shale layers. It represents deeper water sedimentation, very different from the shallow reef sediments. Equivalent rocks further from the shelf edge are simple mudstones. Further north they form the Upper Bowland Shale, which is a source rock for conventional Irish Sea gas-fields and a potential source of shale gas, extracted by the controversial process called fracking.

Here, very near a shelf, limestone dominates.

The shiny black beds are chert – silica layers that formed after deposition. Here’s a single bed of limestone. It is ‘graded’, with coarse debris at the bottom and fine at the top and so likely deposited by a turbidity current. Some of the bits of dead animal forming in the shallow water on the shelf got carried into deeper water by a single major event.

Here’s a closer look at a coarse layer. The fine grained limestone has been partially replaced by chert, which makes the white fossils stand out nicely. There are various sections through crinoid ossicles, which here are completely broken up, as you would expect since they have been transported downhill from where they grew.

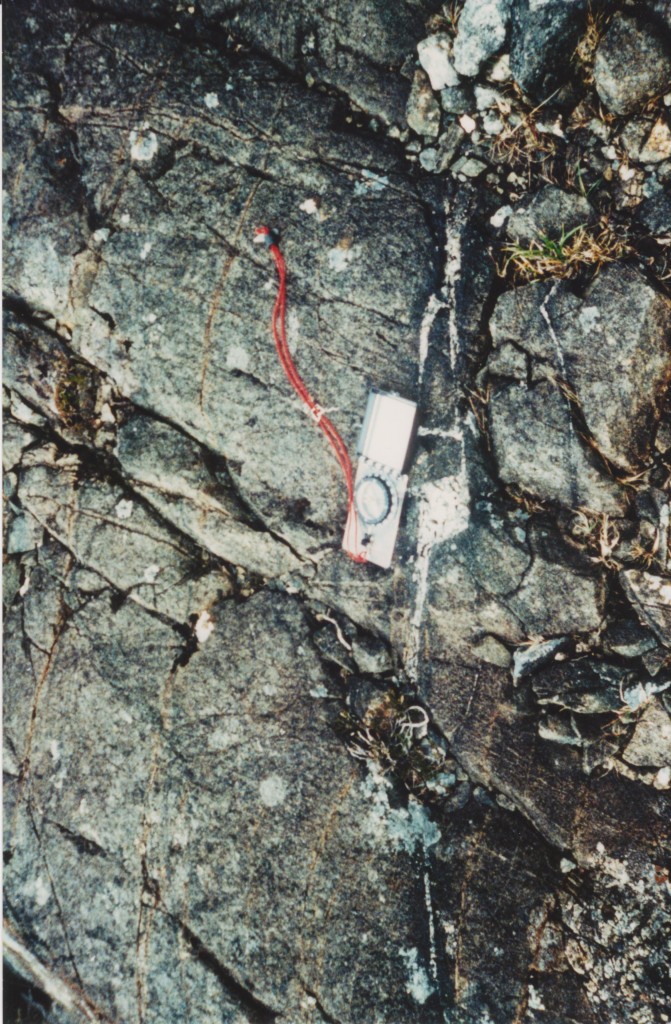

Folding in Derbyshire limestones is rare. Apes Tor in Ecton is unusual in showing tight folds. This is most likely because they are layered and easier to fold compared with the nearby massive limestones. Sadly when I was there the outcrops were heavily vegetated. If you look at the next photo and immediately spot the anticline, you are probably a structural geologist.