Earth science departments are home to three styles of working, each of which tries to answer similar questions, but from very different perspectives. First we have the field geologists. Armed with field gear and a hammer, they gather data from actual rocks in the form of photos, diagrams and above all maps. Next we have those who live in the lab studying rock samples using mysterious machines to gain startling insights. Finally those who seek to recreate the world in a computer, building models to understand the underlying equations that can explain how the earth works.

In some departments the very different cultures and mental models that these approaches require can lead to conflict. But the best science is done when they are combined, in a department, research group or even a single brain. A recent paper by lead-author Andrew Parsons weaves together different techniques to provide a coherent model of how rocks flow to build huge ranges of mountains.

Different ways to build a mountain range

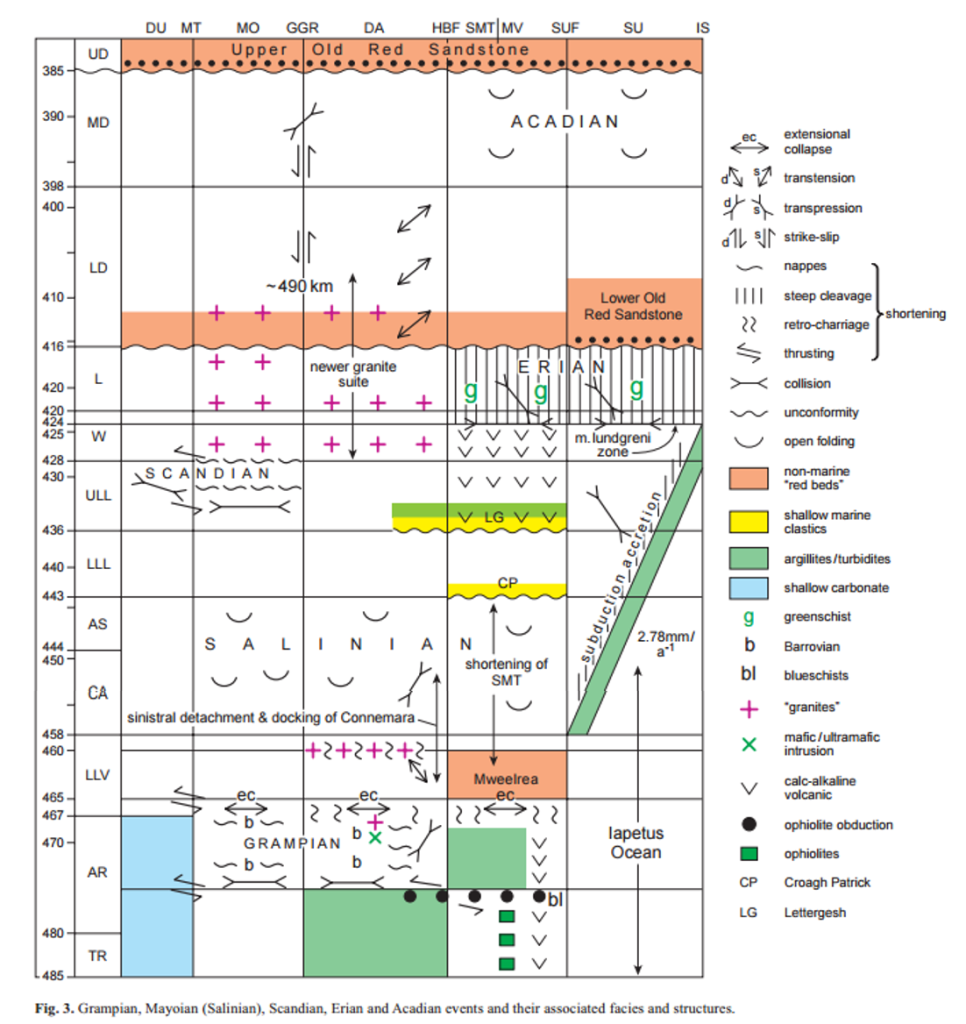

The Himalayan mountain range is the best place to study how mountains form. Sixty million years ago the Tethys ocean sat between the Indian plate and the Asian. Soon the Tethys oceanic crust vanished down into the mantle beneath Asia and the Indian plate collided with Asia. At the site of that collision now sits the highest mountains on earth, plus the huge and high Tibetan Plateau.

Geologically the Himalaya are long (over 2000km), thin and consistent. From Kashmir and Ladakh on the Indo-Pakistan border, through all of Nepal and further East through the Buddhist kingdom of Bhutan the same sequence of rocks is seen. Starting from the undeformed Indian Plain and walking up, we pass through the sub-Himalayan zone, through the Lesser Himalayan Sequence (LHS), the Greater Himalayan Sequence (GHS) and finally the Tethyan Himalayan Sequence (THS).

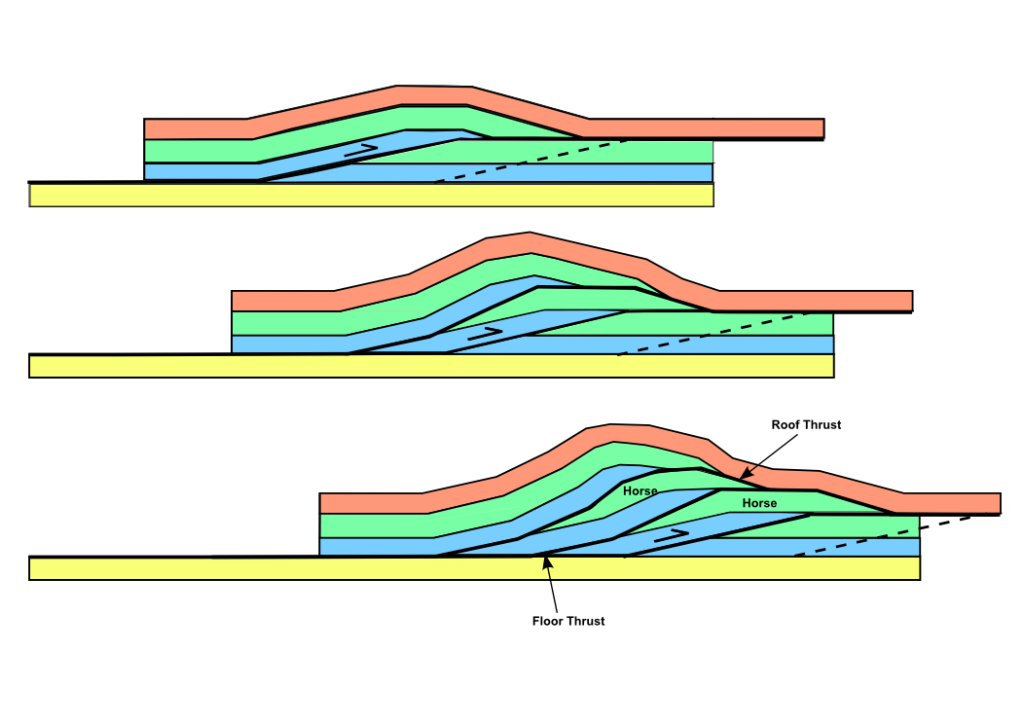

These distinctive packages of rock are separated by major faults. Sudden movements on these faults cause the major earthquakes that regularly affect the people who live in this beautiful part of the world. Early models for how the mountains formed focused on these thrust faults. We saw mountains as thick piles of slabs of rock, separated by brittle faults.

Thrust faults stack up layers of rock. Image from Wikipedia

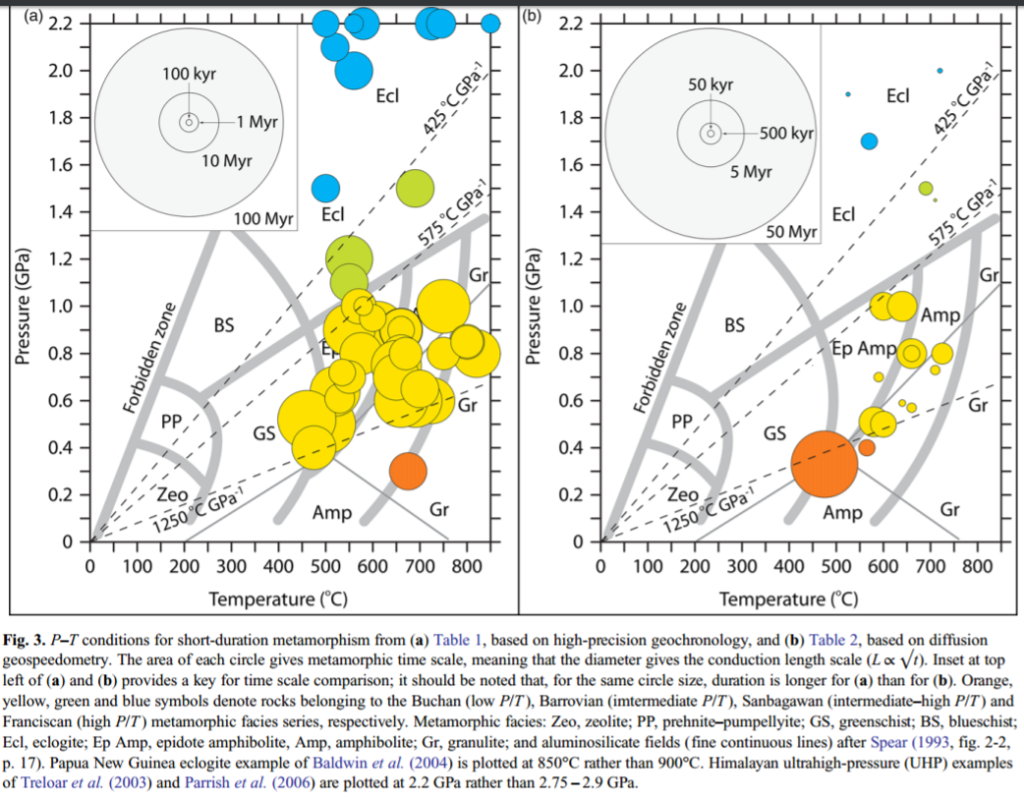

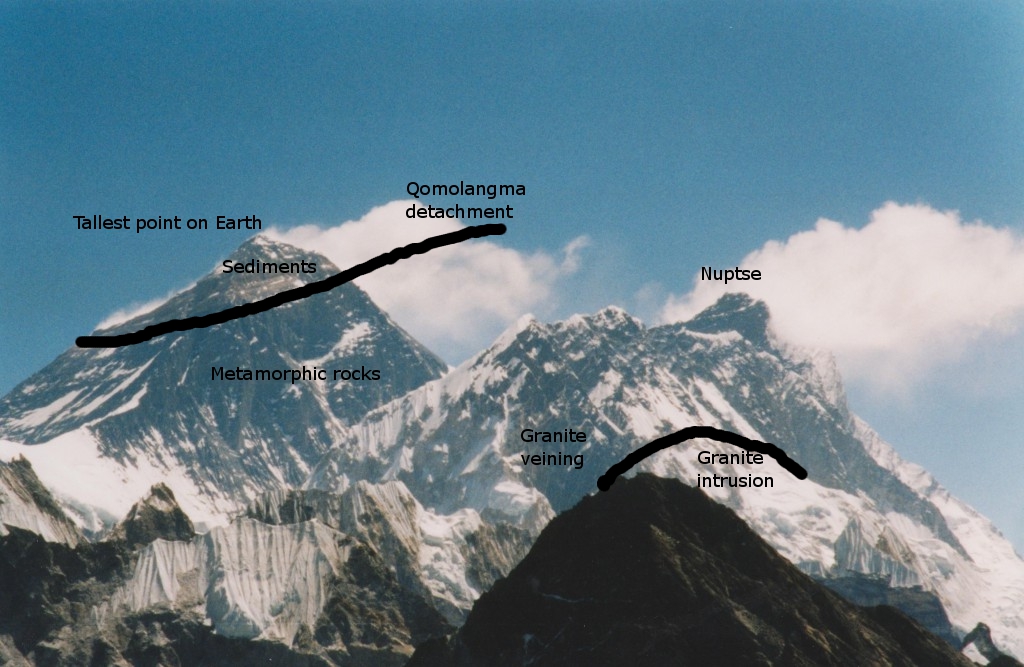

In these models deformation is focused on the thrust surfaces and the rocks in between are relatively strong and rigid. This is a reasonably good description of the rocks of the LHS. However studies of the GHS rocks showed them to have been strongly deformed at high temperatures. Intrusions of granite are common and appeared to form while the GHS rocks were deforming and moving rapidly towards the surface. Also the fault between the GHS and the barely deformed sediments of the THS is a normal fault, one with an opposite sense of movement to the thrust faults.

View of Mount Everest, with sediments of the Tetyhan Himalayan Sequence forming the summit and metamorphic rocks of the Greater Himalayan Sequence below

To explain these features, the concept of ‘channel flow‘ was borrowed from fluid dynamics. This describes how viscous fluids flow when trapped in a channel between two rigid surfaces (think of jam/jelly squeezed out of an overfilled sandwich). We know that hot rocks deep in the earth can flow (slowly!) even while remaining solid. The channel flow concept saw the GHS rocks as flowing out from underneath the Tibetan Plateau towards the surface, perhaps moving into the space created by rapid erosion of the high Himalayan mountains.

An alternative model for explaining the hot and deformed GHS rocks is called wedge extrusion, where deformation on thrust faults brought it to the surface, rather than channel flow.

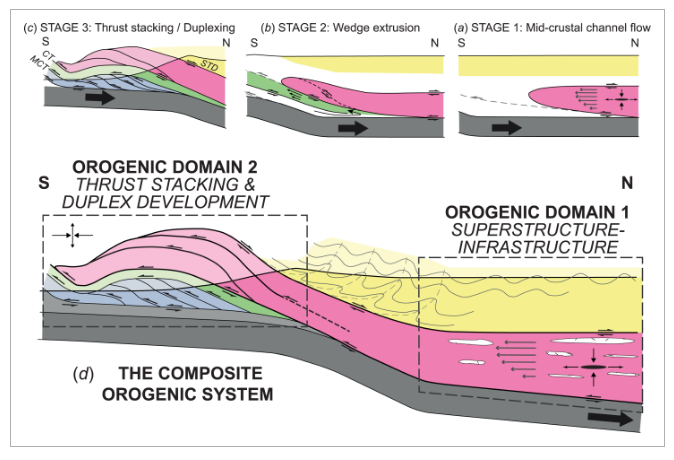

These three models are often seen as being mutually exclusive. But what if all were true?

Going with the flow

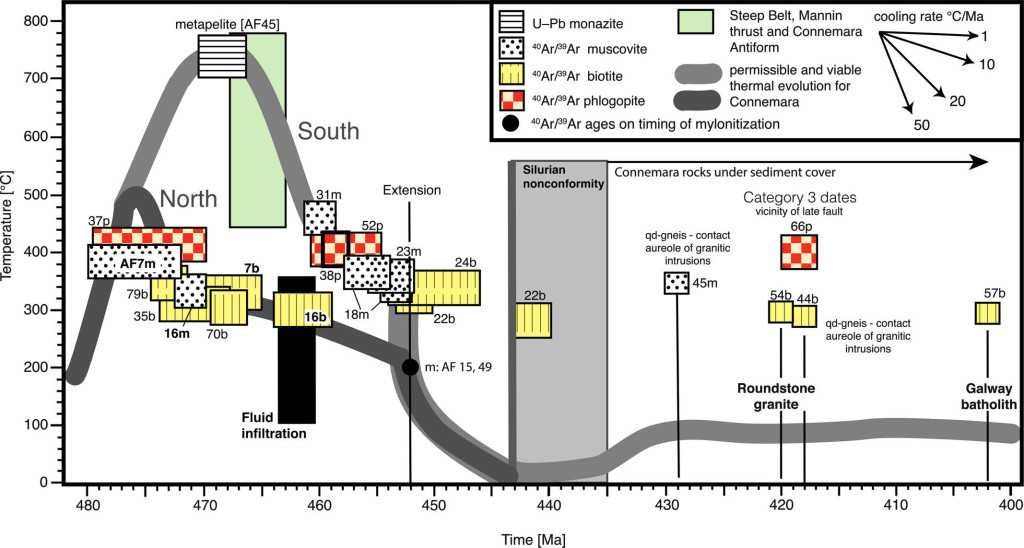

Andrew Parsons work is based upon his PhD studies at the University of Leeds in England. He’s published a map of the Annapurna region of Nepal, covering all the main sequences of rock and so is at home in the fieldwork tradition of the Earth sciences. No doubt he has pictures of himself in field gear, looking sun-burnt and grinning in front of some amazing scenery. At the core of his prize-winning paper is hours and hours of lab-work. After wielding his hammer to collect over 100 samples in a transect across the Himalayas, he had them cut by a diamond saw into thin sections to have their secrets probed.

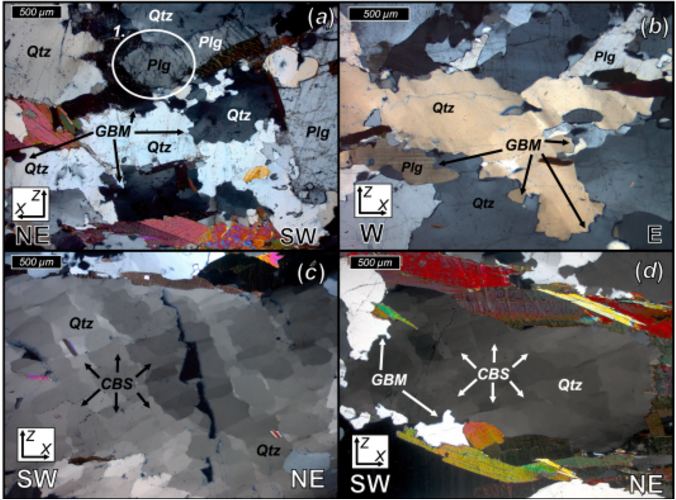

His studies used an optical microscope (to get a sense of this, check out #thinsectionThursday on Twitter) and also a scanning electron microscope. The goal was to identify precisely how the minerals in the sample were squashed.

Rocks are made of minerals and the way they flow is by deforming those minerals. We know a great deal about the many ways common rock forming minerals (like quartz, feldspar, calcite) deform. There are a range of different ways in which the minerals deform. Minerals are crystalline; the atoms within are aligned in consistent repeated patterns. Slow movement of atoms along particular slip-planes or the propagation of defects change the shape of the mineral and so deform the rock. The mineral structure is complicated and different planes of slip are favoured depending on the temperature. Careful study of subtle patterns in the minerals, plus measurement of the average orientation of the atomic structure in each grain tells a great deal.

A portion of figure 6, showing different microscope images of rock samples, with different features highlighted.

For each sample, the authors were able to estimate the temperature at which the rocks were deformed. Also they got a sense of the style of deformation. Imagine a perfect sphere in a rock that is then deformed. Rocks can be flattened turning the sphere into a cow-pat or M&M shape or maybe stretched into a cigar shape. As well as this, the deforming sphere can also be rotated. A combination of field observations, thin section studies and the scanning electron microscope work together gives a view of how the rocks were squashed.

Bringing it all together

The core achievement of this award-winning paper is linking the mass of data to the predictions of the various tectonic models. Channel flow is predicted in the GHS rocks while they were hot and rapidly flowing. The entire channel should flow and rotation only be seen at the edges. This is what the samples from the upper section of the GHS show, plus an indication that this style of deformation ended while they were still at 550°C and changed from being hot and soft to being more rigid.

At this point channel flow ceased and another mechanism, rigid wedge extrusion, came into play. Here the lower portion of the GHS was deforming at a lower temperature. As the model would predict, deformation involves a lot of rotation, consistent with the whole of this sequence of rocks acting as a broad shear zone, bringing the upper GHS rocks closer to the surface.

The lowest temperature deformation is found in a thin zone of rocks within the lower GHS that were acting as a thrust fault, stacking up different slices of rock.

This diagram emphasises the key insight – that different ways of building up mountains can be active at the same time, within different parts of the mountain belt. The mountain building (orogenic) system is composite, made up of different parts. Studying individual mineral grains helps us understand the structure of a massive mountain range. This is because that is how it grew. Countless millions of mineral grains slowly shuffling their atomic lattices over millions of years: this is what builds mountains.

The system is still active, as India pushes into Asia. We know from geophysics that there are hot rocks under the Tibet – perhaps these are right now flowing to the surface as a channel. As the Himalayas are eroded away they will get nearer the surface and start cooling, causing different styles of deformation to come into play.

The terminology of ‘superstructure/infrastructure’ used in this diagram is taken directly from computer modelling work. Numerical models of how mountain belts might work have directly informed this work. Cold rocks near the surface can be a lot stronger than the hot rocks below. By combining computer modelling with field work and lab studies, geologists are getting a good understanding of how the Himalayan mountains formed and have evolved over time. Many places are built on the roots of ancient mountain ranges and high-quality integrated studies such as this help us understand rocks across the world.

Parsons, A. J., et al. “Thermo‐kinematic evolution of the Annapurna‐Dhaulagiri Himalaya, central Nepal: The Composite Orogenic System.” Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 17.4 (2016): 1511-1539.