Aran north

Tim Robinson is a celebrated author and visual artist whose intense engagement with the land beneath his feet is an inspiration to anyone who spends time in wild places. His work is inspired by the idea of ‘the good step’, of reintegrating body and world and achieving a state of consciousness ‘worthy of the ground we walk on’. The maps and books inspired by these abstract ideas contain enormous amounts of very specific information on the geology, archaeology, history, botany, language and folk lore of the West of Ireland.

I first encountered his work in my PhD field area in Connemara. One of the gabbro intrusions I was studying formed a hill called Doughraugh and I wasn’t sure how to pronounce it – the English language being absurdly inconsistent about the pronunciation of ough, as proved by the English towns of Slough (rhymes with cow) and Loughborough (‘luffburra’). I was pointed to Tim Robinson’s beautiful map and gazetteer of Connemara. Along with the location of fairy wells, infant burial grounds and much else, the map shows the placenames in their original Gaelic. Doughraugh, I learnt is a mangling of the Gaelic Duchruach or ‘black stack’ (the ‘ch’ sound is soft as in Scottish ‘loch’ and German ‘ich’).

A black stack (and a castle)

The map improves on the bad job done by an English-speaking cartographer working for the British Ordnance Survey in the Nineteenth century. It uncovers the pleasing fact that the name of the hill reflects the colour of the gabbro that forms it. This is what his work does, again and again and again, his fierce dedication to find out everything about a place creates dizzying connections between forms of knowledge often treated separately. Here the simple fact of a name of a hill is used to spin links between folk memory, past cultural imperialism and the unreflective nature of pyroxene.

When I worked in Connemara I didn’t understand this. It was a time when there were regular terrorist attacks in my country, and the people doing it used the Gaelic language as a badge of difference. Stupidly and wrongly I assumed Tim Robinson was some form of Irish nationalist and looked no further. Consequently I didn’t discover his books until later, when nostalgia for fieldwork and Ireland drew me to them. My love for his work is linked with my personal connection with the places he talks about, no doubt, but you should read them too, even if the closest to Ireland you’ve been is the bottom of a pint of Guinness.

Only a small proportion of his work deals with Geology directly, but he does so accurately and poetically, acknowledging how he draws on his interactions with local experts. Most interestingly, he comes at Geology from the perspective of an artist. For example he writes beautifully of Deep Time, of the awe that contemplating the age of rocks should generate in any thinking person. There is a beautiful section in Stones of Aran: Pilgrimage where he talks about a glacial erratic, covering myth (saints sailing on the stone across the sea) and Geology together. He’s read the scientific papers about the the rock and talks of one exhibiting ‘one of the most lapidary prose styles I’ve ever come across’. He then quotes a chunk of the technical language verbatim and talks about how he, a non-specialist, relates to it – a lovely new perspective on scientific language. Note also the ‘pun’ of using both meanings of the phrase ‘lapidary prose’. Also on Aran, he coins the compelling phrase ‘Aran North’ to talk of the way the joints in the limestone pavement (oriented near to ‘True North’) dominate the geography and define a human frame of reference.

His works are subtly biographical. They are not about him, but in talking about human interactions with the natural world he doesn’t leave himself out. They paint a picture (borne out by some email interaction) of a remarkable man dedicated to his art. There is an asceticism and disregard for material things which resonates with these austere post-boom times. Mostly there is a dedication to truth and the importance of finding out everything there is to know. This is a man who spent decades tramping over small areas of Ireland documenting everything that there is to know about them. To do this, he has learnt from the local people, linguists, historians, botanists, archaeologists, geologists and others. There is a passion in his search for knowledge, as a way of bearing witness to, say, the unknown victims of the Irish Famine as much as to the wonders of the natural world.

Tim Robinson’s thirst for knowledge is an inspiration, a reminder that any research into the natural world is important and interesting because it aims to find out what is true. For me it is also a reproach. Returning to Connemara recently as an ex-geologist and the owner of a garden I was astonished to see fuchsia hedges and huge gunnera plants in ditches (essentially wild garden plants). I had no memory of these. As a young geologist I simply filtered them out of my experience: they weren’t rocks and they didn’t matter. Reading Tim Robinson reminds us to turn off the filters, be like young children and realise that everything matters, everything is interesting.

Frightened terrain

A final reason to read Tim Robinson is his use of language. I have no technical skill to judge, but approving quotes from those who do adorn his book covers. His writing is rich and dense with meaning. One anecdote he tells is of climbing a hill just to think of the right adjective to describe the landscape below. He settled on ‘frightened’. Perhaps not every word has received an afternoon’s consideration, but such attention to the quality of writing yields wonders. Here’s a snippet from his latest book, from the chapter called ‘Subduction’.

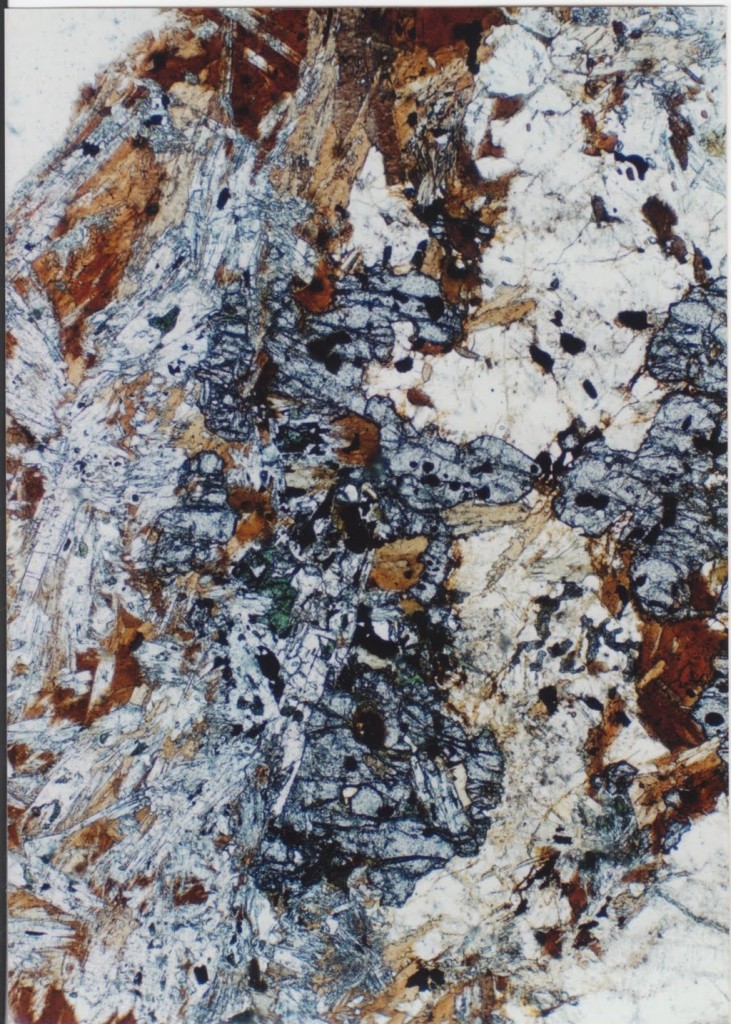

” … and steps into a zone in which the rocks under-foot seem to be resting for a moment between bouts of hand-to-hand fighting. The outcrops are glacially polished as elsewhere, but in their smooth surfaces one can trace a static turmoil of forms – gnarled lumps, twisted and clenched veins, heaped gobbets – that are evidences of some profound convulsion long anterior to the Ice Ages”.

This is an artist’s perspective on an outcrop but he follows it with an accurate description of the science behind these rocks. He creates art about rocks, but the science is in no way in opposition to this. There is no artificial distinction between Art and Science here, or in any of his work. The two are melded together and reinforce each other in a way I’ve rarely seen elsewhere. This is why Tim Robinson deserves to be widely known – his focus is the West of Ireland but his scope is universal. Read him.

Major works

All of Tim Robinson’s work is widely available, but some are best sourced from his own publishing house.

Connemara: Part 1, Introduction and Gazetteer; Part 2, a 1-inch map

If you ever visit Connemara, pick up one of these. A beautiful map and a gazetteer full of masses of information.

Stones of Aran: Part 1: Pilgrimage; Part 2: Labyrinth

Recently republished in the New York Review of Books – Classic series, these are rich and satisfying books. They are long and not for the faint-hearted but once you are drawn into their world you won’t want to leave. Every hill-side, every field, every step even of his journey across a single remarkable island is drawn into a web of meaning, connecting the natural world, Geological time, human history and memoir.

Connemara Trilogy: Listening to the Wind, The Last Pool of Darkness, A Little Gaelic Kingdom

The best place to start is with his most recent works, the Connemara trilogy. Each deals with a small area of land, but the focus is less intense, broadening out to talk much the area’s history, taking in the Irish Famine, British mistreatment and the struggle to preserve the Irish language. It also includes much about those who have visited Connemara over the years, from feuding botanists to Ludwig Wittgenstein.